KUALA LUMPUR, Nov 25 — Non-consensual sexual content — from sextortion to coerced or self-generated intimate images involving minors — is now the most severe online harm faced by children in Malaysia, Unicef revealed, warning that most young victims never report what happened to them.

Speaking to Malay Mail at the Asean ICT Forum on Child Protection, Unicef Malaysia deputy representative Sanja Saranovic said sexualised online abuse has overtaken bullying and scams as the most damaging threat to children, yet remains the least likely to be disclosed.

“There was a clear mapping of harms presented today and non-consensual sexual content is number one,” she said.

“Even if minors record sexual content consensually, consent doesn’t count because they’re children — and this is where we see the greatest risk.”

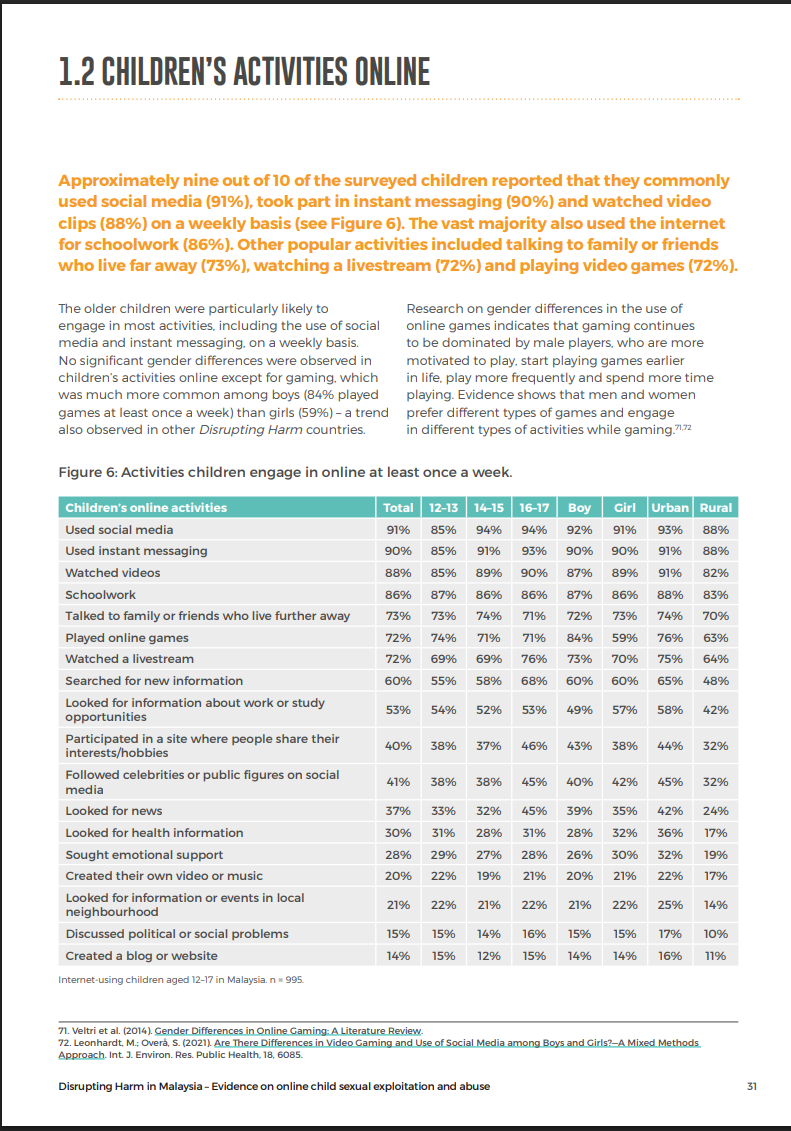

Her assessment aligns with the Disrupting Harm Malaysia 2022 report, which found that 4 per cent of internet-using children aged 12 to 17 — roughly 100,000 young Malaysians — experienced online sexual exploitation or abuse in the past year.

But data from the police’s D11 Sexual, Women and Child Investigation Division shows very few cases ever reach law enforcement.

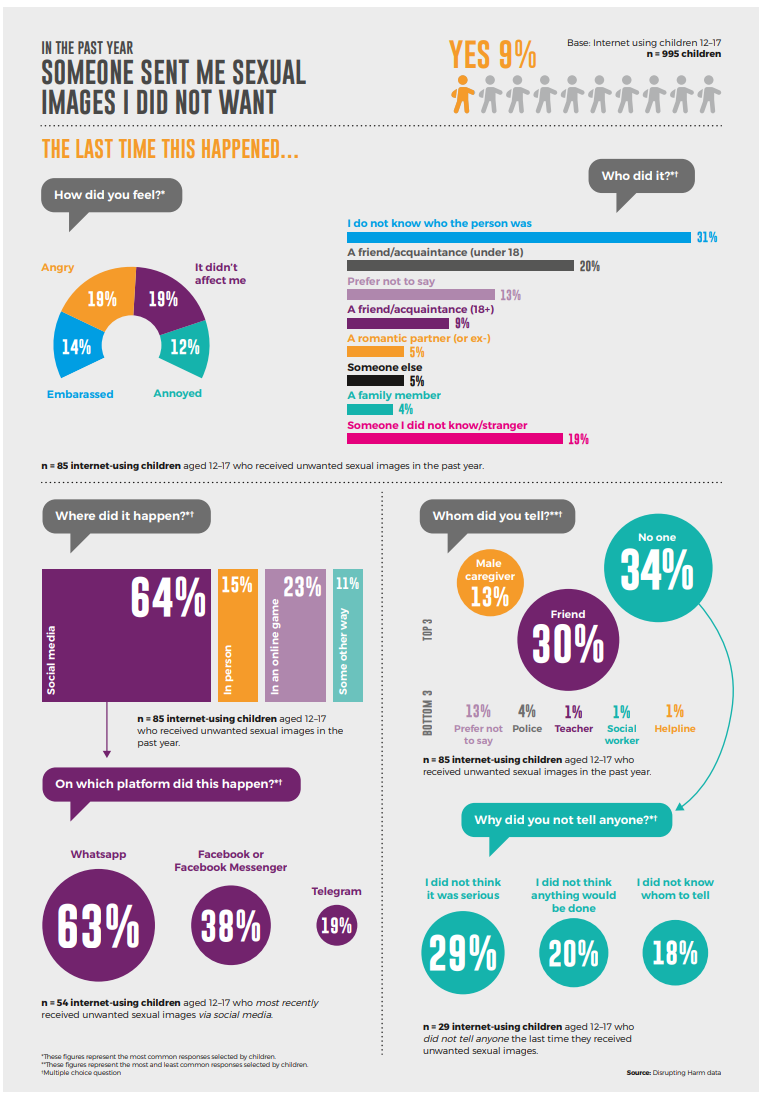

The report found that half the children who faced clear sexual harm online did not tell anyone, and almost none approached authorities. Instead, they confided in friends or siblings, if they told anyone at all, according to cases investigated between 2017 and 2019.

This subset represented the technology-related child abuse cases handled by the unit.

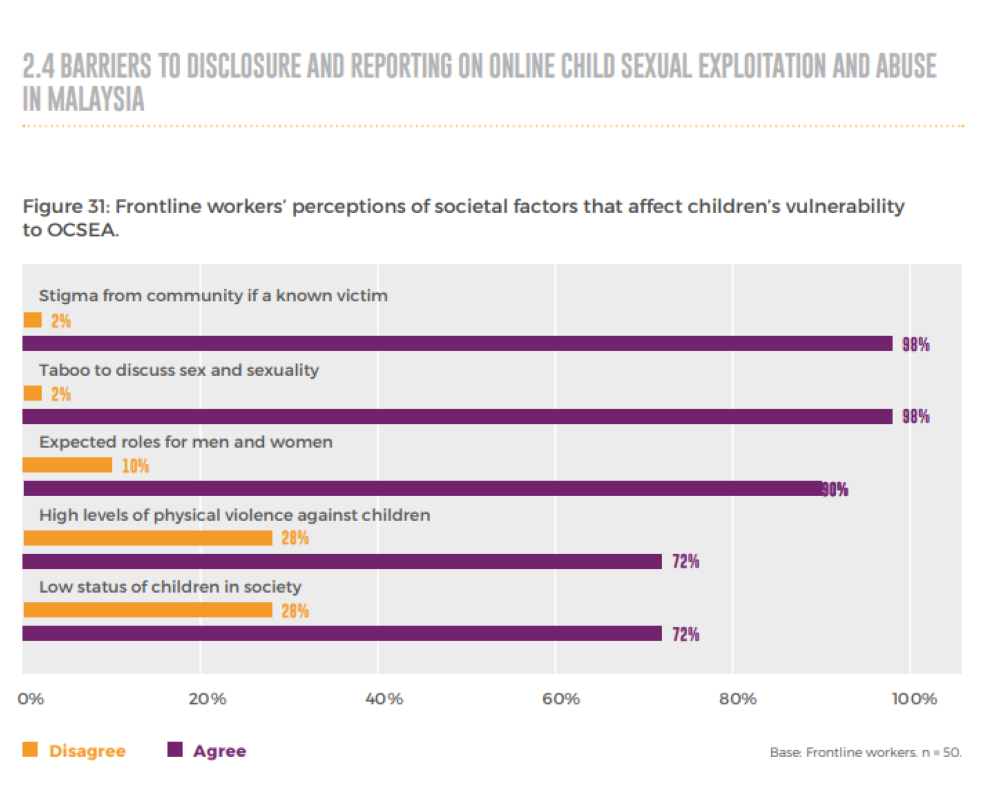

Children cited shame, embarrassment, fear of getting into trouble, not knowing where to report, and the belief that nothing would be done as key reasons for staying silent. For some, fear was compounded by cultural stigma around discussing sexual matters, especially when abuse involved same-sex perpetrators, which could expose victims to further legal or social consequences.

Malaysia not lagging — but must push harder on platforms

Despite the worrying trends, Saranovic said Malaysia is not behind its Asean neighbours. She pointed to recent amendments that legally recognised sextortion for the first time.

“Malaysia has done well to catch up with online and offline risks. What we see here today — ministries, industry, NGOs and even children in the room together — not many countries do this.”

The challenge now, she said, is ensuring technology companies shoulder more responsibility.

Major platforms like Meta and TikTok are generally responsive, but she noted that newer and fast-growing apps — including several Chinese platforms — remain under-regulated and can become breeding grounds for abuse.

“That’s why partnering with industry is essential. Responsibility cannot fall only on parents or children. Children at young ages can’t judge what’s safe or unsafe, so platforms must make safety a baseline,” she said.

The Ministry of Women, Family and Community Development is expected to continue engagement with tech companies after the forum to push for stronger content moderation and faster removal of harmful material.

Children as young as nine affected

Saranovic said cases can begin “as early as nine”, though the lack of consistent data remains a major gap. The Disrupting Harm report also flagged this, urging Malaysia to establish continuous monitoring rather than relying on fragmented or ad hoc reporting.

The report found that 56 per cent of children did not know where to seek help if they faced online sexual abuse, while 34 per cent did not know how to report harmful content on social media — pointing to a widespread knowledge gap rather than unwillingness to report.

Sex education still limited — and cultural sensitivity matters

When asked how Malaysian children can be taught about sexual risks in a Muslim-majority context, Saranovic stressed that sexual education can be contextualised without being omitted.

“There is research that open engagement helps children recognise what is right and wrong,” she said. “Cultural context matters, but you can design programmes that fit the environment we live in.”

The Disrupting Harm report noted that 60 per cent of Malaysian children had not received any form of sex education in the past year, leaving many unable to recognise predatory behaviour, coercion or harmful content.

Ban vs delay — and why Unicef prefers skill-building

Some countries, such as Australia and Denmark, have moved to delay children’s access to social media until the age of 16. But Saranovic said there is no evidence that bans reduce harm.

“Banning doesn’t work. Skill-building works,” she said.

“Children should be active users, not passive ones. You gradually expose them and teach them how to navigate the risks.”

She shared an example from the forum where a parent gave a phone to a three-year-old but limited use to the camera — a method of building digital literacy step by step.

Saranovic’s final message was directed at parents.

“Most of the time, kids don’t report because they fear being judged or punished for something they didn’t fully understand,” she said.

“Parents must be open-minded. Create a safe environment so children can tell you when something is wrong.”

She also urged parents, schools and communities to work together, saying no single group can tackle online child harm alone.

“Schools cannot solve everything. Parents cannot solve everything. Government cannot solve everything. It has to be a partnership,” she said. - malaymail

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.