Over the past three months, Malaysia witnessed one of the most extraordinary party elections in its short history.

It took place over nine weekends, involved an electronic voting system, voting was open to every member and its winners were announced even before the official results were released.

This article seeks to explore what Malaysians can learn from PKR elections, identifies democratic inhibitors and proposes some solutions for internal elections for political parties.

What is PKR?

PKR currently has the most seats in Parliament and hosts a prime minister-in-waiting. It is the only party in Malaysia that aspires to be mass-based. Currently, the party has lawmakers from every state except in Kelantan and Terengganu. PKR has lawmakers representing rural and urban constituencies.

This is unlike parties of equal strength such as Umno, which is not represented in Sarawak and does not aspire to represent the non-bumiputera. PKR is also not similar to the DAP, which primarily focussed on urban constituencies.

From the outset, PKR was intended to be “catch-all”. It was to be an organised incarnation of Reformasi that sought legitimacy through the ballot box.

Over the years, PKR became a hub for libertarians, religionists, trade unionists, socialists, environmentalists, rights activists, regional activists and philosophers, among others, seeking to find a middle-road approach for Malaysia.

About a decade after its inception, the party jettisoned the practice of having small group of delegates choose the party leadership and instead granted voting rights to all members to further cement its reputation of being inclusive and mass-based.

Were the PKR elections democratic?

The short answer is yes. On the surface, voting was free and mostly fair. However, when examined in detail, some aspects of the elections would appear to be inconsistent with democratic practices.

Firstly, some 800,000 members were given the right to vote but only a fraction did so. At the time of writing, the turnout rate is still unknown but based on Malaysiakini’s observations, the turnout rate nationwide was probably around 20 percent.

Not voting is part and parcel of the democratic process. However, the low turnout would make it difficult for PKR to claim that it practices participatory democracy since the majority of its members are unwilling to decide on the direction of the party.

Secondly, voting was evidently less about making informed choices, merit, policies or even personalities but more about the “cai”.

The term “cai” evolved from the term “cai dan” or “restaurant menu” in Chinese. In the Malaysian political context, the “cai dan” usually serves as a voting guide issued by competing teams. It normally contains photographs of candidates and their corresponding numbers used for the elections.

The term “cai dan” rose to prominence during MCA’s leadership election and was later adopted in other parties, albeit with the “dan” removed.

In the case of PKR, virtually every voter carried a “cai” to the voting booth. Sometimes, the “cai” didn’t even contain photographs or names and instead featured only a set of numbers to guide the voters when keying in details into the voting machines.

The “cai” practice does not encourage individual scrutiny of candidates and instead voters choose wholesale, typically, based on which team their local leaders are on. The element of making informed choices is therefore diluted.

Suggestions to mitigate problems arising from the “cai” method of campaigning are discussed later.

Thirdly, there was evidence of race-based voting. Some local PKR divisions had voted overwhelmingly for candidates of one ethnic group, even extremely obscure candidates who were largely ignored by PKR divisions elsewhere.

Voting based on race instead of merit is again inconsistent with democratic values. Having a fair platform for all candidates to articulate their views may mitigate this problem.

Fourth, there was evidence of collusion among candidates. Unlike the general election, the turnout for the PKR election did not reflect the same sense of urgency or importance. Therefore, PKR candidates had to mobilise members to vote instead of expecting them to vote out of duty.

This created the opportunity for collusion among candidates who would strike deals for votes with other candidates by offering reciprocal treatment in their respective strongholds.

This created the opportunity for collusion among candidates who would strike deals for votes with other candidates by offering reciprocal treatment in their respective strongholds.

This could explain why a PKR division in Kelantan had voted overwhelmingly for a new PKR member, who had only joined the party after the May 9 election, over established candidates in the central leadership council (MPP) race.

Therefore, candidates with more resources and better networks may have had an advantage over a candidate who offered himself or herself purely on merit.

Fifth, the election process was not transparent. Malaysiakini, upon the request of readers, had produced a special website to track the elections. Malaysiakini had to rely PKR’s official elections page for data which until today – a week after the conclusion of the elections – has yet to be fully updated.

Although this is probably unintended, the opaque nature of the results has naturally undemocratic consequences.

Lastly, the integrity of the voter list was questionable. Malaysiakini had shared its discovery in September that the party’s membership had increased by at least 40 percentin June.

The party had offered limited voting rights to members who joined before June 26. Although the official line was that people who joined on their own volition after the May 9 elections, owing to the party now being in government, it is plausible that recruitment sometimes took place in an organised fashion with the party election in mind.

Malaysiakini has observed that it is common for many political parties throughout Malaysia to see a significant spike in membership during years when internal elections are held because voting at the local division level is normally open to ordinary members.

As for PKR’s elections this year, there were some divisions which saw June recruitment figures bordering on the absurd. During the elections, some of these divisions became the focal point of one team.

Eventually, the PKR elections were less a competition of ideas and instead, a competition of who had the resources to recruit or mobilise the most voters.

Moving forward

PKR should be commended for its efforts to introduce a mass-based political party to this region and an internal election system that was intended to be democratic and inclusive.

However, this article has highlighted many shortcomings of the electoral process which other political parties should take heed of, in conducting their own elections.

Moving forward, PKR, which is scheduled to hold elections again in 2021, should consider a revamp of its election system.

Firstly, the number of voters should be reduced in order for the elections to be manageable. This will not dilute the democratic aspirations of the elections because the turnout since 2010 has always been well below 50 percent.

An electoral college system, similar to what is being practiced by Umno, is perhaps the best option for PKR.

The Umno system provides for equal weightage among all regions and discourages efforts to pad up membership numbers just for the sake of an election. Umno’s voting base is also big enough to discourage vote-buying attempts.

Secondly, the practice of “undi ragu” – a category of voters who are allowed to vote despite not being on the voter list – should be abolished.

If it is the responsibility of ordinary Malaysians to ensure that their voting records are in order, the same should be expected of PKR members without exception.

Thirdly, the campaigning process should be governed by a clear set of rules. In 2008, during the US Democratic Party presidential primaries, three candidates campaigned across the country for the right to stand as the Democrat candidate for US president.

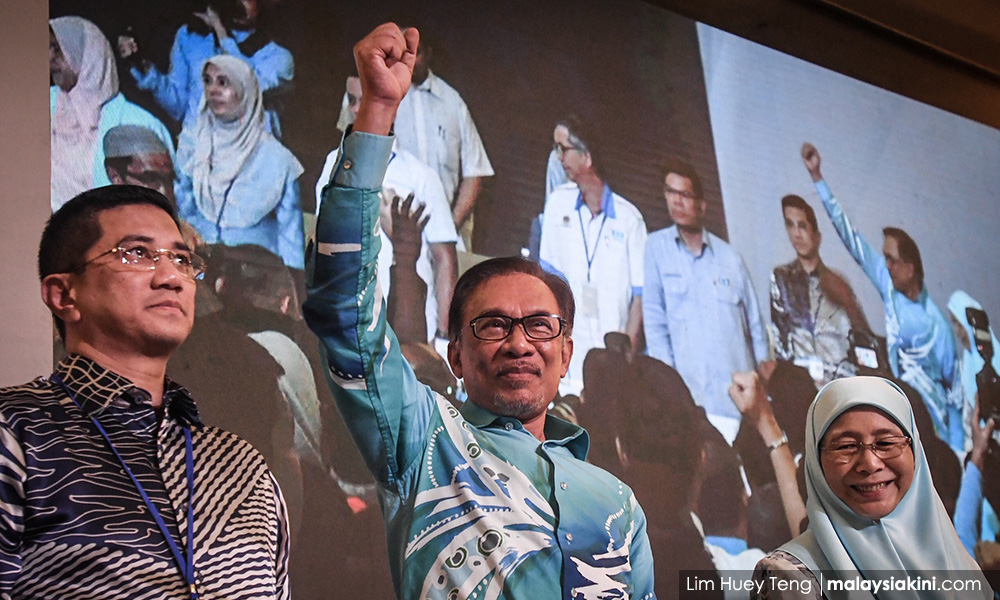

The US campaign was marked by 26 rounds of televised debates. In contrast, the two main candidates for the PKR elections – Mohamed Azmin Ali and Rafizi Ramli – and their proxies barely engaged each other in public.

Having a clear set of rules to compel those vying for top positions will only enhance the democratic process by encouraging competing teams to set forth their agenda on a fair and highly visible platform.

Lastly, the prevalence of “cai” as a determinant for voting can be mitigated by providing an even platform for all candidates. For example, the official elections website can contain a webpage for all candidates to upload their basic information, their achievements and embed a video of a short policy speech.

The webpage can even include a mechanism to build a personalised list, or DIY “cai”, which voters can either print or view on their mobile phones to assist them when voting.

Commendable aspirations

PKR’s recent leadership election has been called many unsavoury things but its aspirational goals – to be mass-based and democratic – was a commendable one.

It is the intention of this article to highlight the many inconsistencies with that goal in hope that Malaysians will recognise the importance of ensuring that the integrity of the electoral processes and the spirit of representative democracy, at every level, must be upheld.

Political parties all seek to govern and those who will potentially be governed must hold their potential governors to the ideals that they claim to profess.

ANDREW ONG is a long-time member of Malaysiakini’s editorial team. He was involved with Malaysiakini’s special page to track the PKR elections. He hopes the PKR Central Election Committee (JPP) will release the verified results soon so the page can be updated. - Mkini

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.