As schools stand to remain closed for much longer, experts have implored the government to take immediate steps to help students left behind by home-based and online learning initiatives.

They have deemed existing measures insufficient and proposed a list of interventions that include loaning out electronic devices and providing free mobile Internet data.

Alternatives to online lessons should also be considered - like maximising the use of terrestrial television, radio and physical worksheets for educational purposes.

Students have already spent seven weeks outside the classroom under the movement control order (MCO). Experts warn that a further delay in responses could result in long-term adverse effects on those who do not have the means to adapt.

The ideas in this article were drawn from conversations with former education minister Maszlee Malik, former deputy education minister Teo Nie Ching and education non-profit Teach for Malaysia CEO Chan Soon Seng.

Also referenced is the Khazanah Research Institute article entitled “Covid-19 and Unequal Learning” by Hawati Abdul Hamid and Jarud Romadan Khalidid.

Get devices to more students

Needy students have to be equipped with electronic devices necessary for online lessons, or e-learning.

Despite encouraging teachers to migrate to e-learning, a survey by the ministry last month found a deep digital divide among Malaysian households that has impeded the teaching method.

Of the 670,000 households surveyed, 36.9 percent said they had no access to electronic devices at all. Only six percent had personal computers and even fewer (5.7 percent) had tablets.

Teo (above) suggested that the government take a cue from Singapore and loan out existing devices to households who need them.

“It would not have much of a cost implication to lend out existing laptops and devices to students. Of course, there is always the risk whereby devices are not properly taken care of.

“We need to make sure they understand how important it is to take care of things. This is something we can work out,” she said.

Before it announced its “circuit breaker” - an equivalent of the MCO - the Singapore government had conducted a survey to identify students who did not have devices at home for e-learning.

It was reported that the Singaporean Education Ministry then provided 3,300 devices and more than 200 Internet dongles to these students. Some needy students were also allowed to come back to school to use computers under teacher supervision.

Hawati and Jarud also proposed a loan scheme for devices, along with grants or tax reliefs to encourage families to purchase devices.

“A programme similar to the 1Malaysia Netbook Project implemented in 2010 involving the distribution of 1.2 million netbooks to less fortunate students should be rolled out again,” the researchers added.

Chan, meanwhile, pointed to the Communications and Multimedia Ministry’s Universal Service Provision (USP) programme to fund these initiatives.

Under the programme, telecommunications companies contribute to the USP Fund to help provide communications infrastructure to underserved areas.

In 2018, available funds stood at RM3.8 billion - a portion of which has since been designated for the government’s National Fiberisation and Connectivity Plan.

Chan proposed that the remaining money from the fund be utilised to purchase devices for families in need for e-learning.

Connect students to the Internet

Another key requirement for effective e-learning is sufficient Internet data.

Even when they had the devices, parents in both urban and rural areas previously told Malaysiakini that they were struggling with a lack of high-speed Internet and mobile Internet data.

Even in the most industrialised states in the country, data from the Communications and Multimedia Ministry (MCMC) showed that less than 15 percent of people had access to home Internet. In less-developed states like Kelantan and Sabah, only about two percent of inhabitants had fixed broadband.

Cognisant that most Malaysians rely on their mobile phones for Internet access, the government previously announced that it had worked with telecommunications companies to provide each mobile phone user with an additional 1GB of free Internet data per day.

Hawati and Jarud opined that this was not enough.

“(This) is not adequate to support heavy video streaming or class teleconferencing which exhaust data quickly. This puts children of poor families at a disadvantage as they cannot afford to ‘top up’ data more frequently,” they said.

A one-hour Zoom video conference at 720p, for example, needs 1.35GB of data.

Chan proposed that the government embark on a broader response by getting all Internet providers to give needy children better connectivity.

During the MCO, telecommunications company YTL provided SIM cards with 40GB worth of data for free to government school students. It also gave out free mobile phones with 120GB worth of data, limited to 10GB per month, to students from B40 families.

Both are part of its “Learn From Home” initiative aimed at facilitating e-learning for the underprivileged.

“One provider is fine but how do we get a response from all the providers?” Chan asked.

With devices and sufficient data, students gain access to a world of resources like the Education Ministry’s educational television streaming service EduwebTV and teacher-hosted videos on CikgooTube.

It also connects them to classroom-specific programmes like Google Classroom and lessons over video conferencing on platforms like Zoom.

Having more students with devices and data also unshackles teachers from limitations, allowing them to experiment with different digital solutions to make learning more interesting.

Expand educational TV

In light of gaps in access to e-learning, free-to-view terrestrial television channels could be better utilised to facilitate teaching and learning by covering more hours, subjects and languages.

Presently, RTM’s TV Okey airs “Kelas@Rumah” lessons for two hours a day. One hour from 9am on secondary school subjects and one hour from 1pm on primary school subjects.

The programme is usually published the day before, and lessons are taught in Malay or English.

Maszlee (below) proposed that RTM expand the lessons beyond just two hours and said that other state-owned free-to-view channels like Bernama TV and TV Al-Hijrah ought to contribute.

“Private television channels, too, should play their role,” he said.

He pointed to Indonesia where public television broadcaster Televisi Republik Indonesia (TVRI) airs full-day education programmes to help students of all levels - from pre-school to senior secondary - learn from home as schools are closed due to the Covid-19 outbreak.

Lessons, along with a programme for parents and teachers, run from 8am to 11:30pm on weekdays. On weekends, the broadcaster airs cultural programmes and Indonesian films.

Following the Covid-19 outbreak, the New Zealand government also set up two new channels for education content - one in English and one in Maori.

Lessons run for six and a half hours and include content for how parents can facilitate home-based learning.

Teo also opined that two hours of lessons a day were insufficient and proposed that vernacular school subjects be included in RTM’s programme.

“The ministry can work closely with RTM to make sure we have more channels and also (make them) multilingual so that the needs of the students in the vernacular schools are also well taken care of,” she said.

Use radio for lessons

Maszlee further proposed that lessons be broadcasted over the radio.

Education programmes are presently not aired on radio waves.

RTM has six national radio stations and a station for every state in Malaysia.

It also has 13 local radio stations. Limbang FM, for example, caters to listeners living in Limbang, Sarawak.

Quoting MCMC statistics, Hawati and Jarud noted that the radio was capable of reaching 20 million people, equivalent to 61 percent of the population.

“Subjects that require less visual aids and more storytelling, such as history, can be effectively taught through this channel. This would be helpful, especially for students in rural areas without access to the Internet,” they said in their article.

Resource centres for printed work

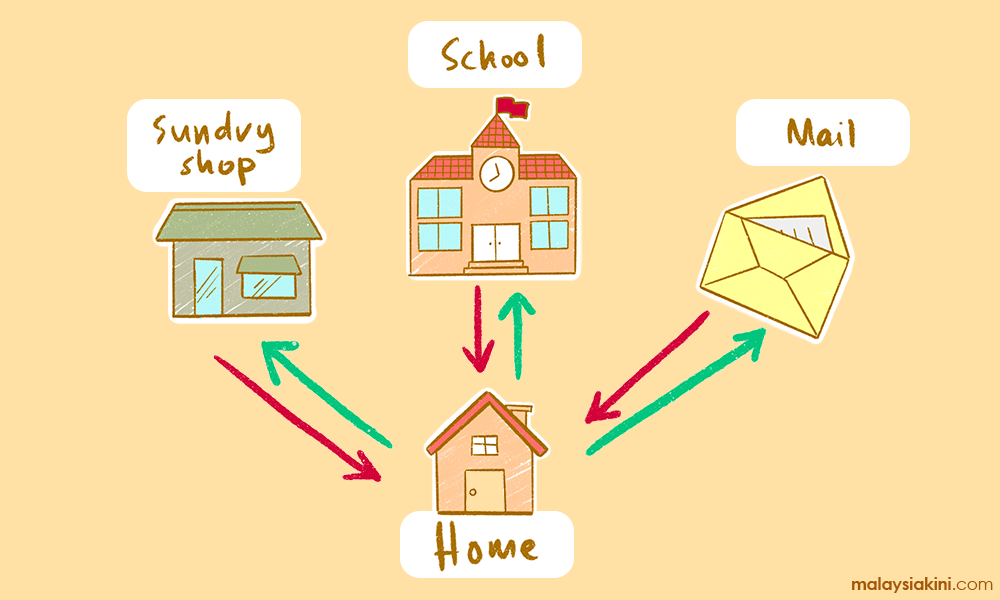

Another alternative to e-learning is distributing printed worksheets by mail or through resource centres.

Chan proposed transforming schools into such centres where parents could pick up and drop off worksheets for their children.

“For families that have no Internet access, schools can open up as distribution centres.

“Parents can come to school to pick up resources to take home, children can work on these resources at home and parents can bring them back to school when they are done, as well as receive a new work packet,” he explained.

Aside from schoolwork, schools could also double-up as a distribution centre for daily essentials for these families.

Similarly, local shops or sundry stores could be used as such resource centres.

As with the school idea, parents could pick up and drop off printed schoolwork for their children from their local store when they head out to buy groceries. Teachers, in turn, can pick up and drop off work packets at these stores.

Another method is to have teachers mail physical worksheets to individual students.

Under a March 27 ministry circular to teachers, the distribution of printed materials during the MCO was explicitly prohibited as it involved movement. Teachers were instead encouraged to use e-learning or materials students already have at home.

Chan urged a relaxation of this prohibition to enable disadvantaged and rural students to continue with teaching and learning, especially as Malaysia enters the recovery stage of the outbreak and slowly reopens the economy.

Long-term effects

Underprivileged students have been struggling with remote learning for the past one and a half months.

Should the situation persist, Hawati and Jarud expressed concern over the long-term effects this could have on their life opportunities, prospects and social mobility.

Higher dropout rates could be one potential outcome.

“We need to rapidly scale up technological adoption and bridge the digital divide in e-learning.

“If not undertaken with due haste, the possible adverse long-term impacts on school children will only serve to widen existing inequalities and undermine social cohesion,” the researchers cautioned. - Mkini

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.