On a day to honour the birth date of Raden Adjeng Kartini, an Indonesian national hero, women's rights activist Rusni Tajari said women in privileged positions can embrace her spirit to empower other women and rise above socio-economic challenges or traditions that bound them.

Speaking to Malaysiakini, Rusni said there are many lessons to be learnt from Kartini, who is honoured every year today on her birth date, April 21, 1879, for her contributions to furthering women’s rights to education.

The eldest daughter of a high-ranking Javanese family, Kartini was bound by strict traditions and a patriarchal mindset that relegated the role of women to only being wives and mothers, from their earliest teenage years.

Through her own will, Kartini gained access to modern education during the time of Dutch colonialism. In her 25 years, she became known for her writings on women emancipation, the most famous being a collection of her letters to pen pals in Europe, first published in 1911 before eventually translated to other languages.

“She mostly wrote about how women in those days were bound by early marriages and polygamy, telling her Dutch pen pal that it was not a good culture.

“Kartini came from a privileged background, but she realised that with her access to education, many other women were still left out,” said Rusni, a Sabahan with Indonesian roots.

She said shared cultural experiences between Malaysia and Indonesia, to this day, allow for many parallels to be drawn from Kartini’s struggle.

“We can see how the culture of patriarchy still has strong roots here. Back then, Kartini fought for women’s rights to education, a rare call as most were afraid.

“There were not many enlightened women, so Kartini felt she needed to fight, refusing to be alone in her enlightenment. She could gain access, but not the others.

“We have the same situation here (in Malaysia). We have women from highly educated backgrounds, with good economic access, equal opportunity... but not all are so lucky,” said the senior advocacy officer.

From their privileged positions, Rusni said women should be more aware of class issues and how they could push for others to have access to more opportunities, including in the time of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Looking back, Rusni said academic empowerment has always been an issue close to her heart too, as she had parents who did not go to school but succeeded to put all their children through university.

Understanding the importance of education, Heny Saroso is just one of many Indonesian women driven by socio-economic pressures to leave home seeking a better future, having worked as a domestic helper in Malaysia for the past 14 years.

“When I first came, my eldest son was in Form 5, and the youngest was only two. My youngest was born with a heart defect, so all our savings were gone.

“I saw that my eldest son was smart, he wanted a chance to enter university, but we had no money. So I willed myself to come here (Malaysia) so that he can further his studies,” Heny told Malaysiakini.

Since then, Heny said she has been working only to support her youngest son, now in high school, while her three other children have graduated.

“That is my main aim, for my children’s education. Not to build a grand house or anything of that sort. My children’s education, that’s my greatest treasure,” she added.

Aside from her children’s education, Heny said she discovered her own opportunities to learn as well, particularly since the start of the Covid-19 pandemic.

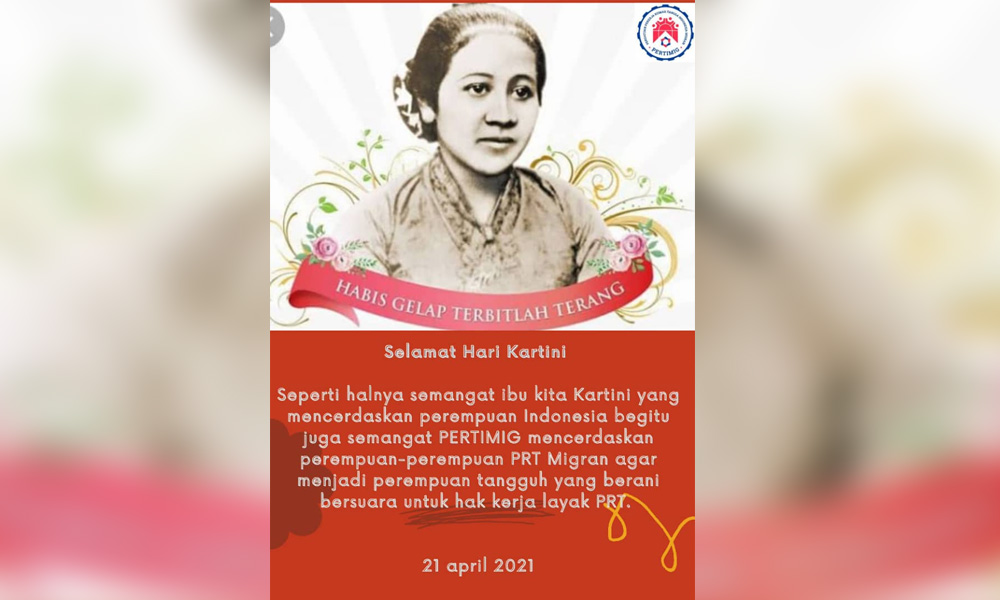

Through online classes conducted by Pertimig, a Kuala Lumpur-based Indonesian grassroots organisation, Heny said Indonesian migrant workers were empowered with new skills that would serve them even after returning home.

“With that, we will not only know about ‘kitchen affairs’ but also other matters,” she said, adding that many women in her position were inspired by Kartini’s belief in the power of education.

Having dropped out of school to work as a domestic helper in Malaysia and later Singapore, Yulia Endang said she was inspired by an opportunity offered by the Indonesian Embassy to sit for the high school final examination, which eventually allowed her to earn a degree in English Literature.

“Juggling between work and school was definitely tiring, but it would have been more exhausting to give up without trying.

“As time passed, I felt my work as a domestic helper was not an excuse to stop studying, but rather a motivation to prove my ability,” she told Malaysiakini.

Beyond formal education, Yulia, who harbours a dream to become an English teacher, urged Indonesian migrant workers to make use of other available learning opportunities, now made easier with online access.

Back in Malaysia, Rusni named the late Shamsiah Fakeh, leader of Angkatan Wanita Sedar (Awas), as her choice for a figure in history worthy of the same recognition granted to Kartini.

At the same time, Rusni also sees a future in her own daughter, two-year-old HR Kartini, which, not by coincidence, is named after the women's rights icon. - Mkini

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.