The abrupt termination of Russian humanitarian worker Valeriya Astashova’s permit to conduct English language classes at an Orang Asli village in Perak is yet another setback for her in the past year.

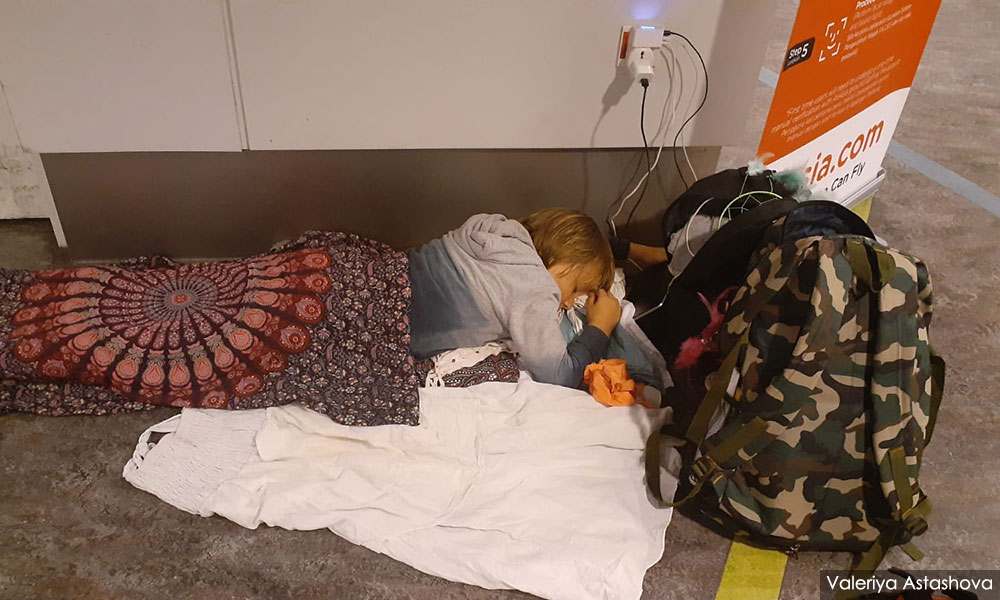

In March 2020, Astashova and her nine-year-old son Kyri first made headlines when they were among a number of foreigners stranded at the Kuala Lumpur International Airport 2 (KLIA2), due to countries around the world closing their borders in the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic.

The 32-year-old, who has run a hostel in Koh Tao, Thailand, for the past seven years, told Malaysiakini that she initially came to Kuala Lumpur in February 2020 to volunteer at an Afghan community centre in the country.

“My best friend said I was working too hard at the hostel and told me to go and do whatever I wanted to do for one month, so I was looking for different travel and volunteer opportunities and that is how I found the Afghan community centre in Kuala Lumpur,” Astashova said in a phone interview yesterday.

She said she has always been passionate about taking care of people. For example, she volunteered at the local orphanage when she was living in Pattaya, Thailand, as well as an old folks’ home when she was studying in the Czech Republic. She has also been on humanitarian missions at refugee camps.

Astashova, who holds a Bachelor's degree in international relations and a Master's degree in philosophy and religious studies, credits her grandfather for her interest in hospitality and serving people.

“My grandpa loves serving people. He raised me, so that is why. He wouldn’t even walk past a homeless person on the street. He would not just give food, but he would sit down and talk to the person and try to find the person a place to stay for the night.

“He is my hero, the best human being probably in the universe. Even now he is nearly 90 years old, and he has been trying to open a library in his hometown and he has been fighting the local council for it.

“My grandma is so angry because he is 90, he should stay at home,” Astashova recounted with a laugh.

Though Astashova had initially planned to volunteer at the Afghan community centre for two weeks in February 2020, when she arrived and saw that it was in dire financial straits, she and the other foreign volunteers decided to extend their stay to two months, in order to try to save the centre.

That was when she also decided to make a quick trip back to Thailand to fetch her son, as she realised she would be staying longer than expected.

“Thank goodness I went to pick him up because, otherwise, we would be separated for a long time,” Astashova said.

Stuck in KLIA2 arrival hall

When the Covid-19 pandemic started escalating in the region, she booked a flight home to Thailand but all non-Thai citizens were sent back on the same flight when they arrived in Bangkok.

“We were so excited to be going home, then we landed in Bangkok and we got out and there were men with machine guns and doctors will full equipment. Everything started getting scary,” she recalled.

With her there was also a group of Polish nationals who were merely transiting in Bangkok before their connecting flight back to Poland, she recalled.

“A Polish lady tried to object, saying we have all the documents, but when you face men with machine guns, you don’t feel like arguing with them for too long,” Astashova said.

Yet, the Malaysian immigration also refused to let them leave the arrival hall when they were forced to return to Kuala Lumpur.

“It’s not even the airport, it’s the arrival hall where we were locked. Concrete floors, four rows of plastic seats. No shops, no restaurants, no hotels,” she said, addressing some who questioned why they did not check into an airport hotel at the time.

For three days she called anyone who she thought could help her, including those at the Russian Embassy, who advised her to fly back to Russia.

At the time, she said, not only were the flights back to Russia too expensive, but she also had almost no support network in Russia.

“I have my grandparents in Russia who live in a small town, but apart from that, I don’t have anyone. My home is in Thailand, I have my dogs, my cats and 11 chickens. Who is going to take care of them?

“I also don’t have any winter clothes. If I land in Russia now with my son, what is going to happen to me?” she said.

After being stuck at KLIA2 for several days, Astashova and Kyri were eventually allowed to leave the airport. But that was only the beginning of their troubles.

Though they were now in Kuala Lumpur, she and her young son were still vulnerable and exposed to dangerous situations. They were forced to change accommodations a few times, as they tried to survive with almost no money.

Astashova also admitted that she was embarrassed about getting stuck in another country at the time, which was why she did not reach out to friends for help in the beginning.

Humanitarian work

Eventually, she managed to save up some money and no longer felt like she had to struggle to survive, which was when her mind turned back to her initial reason for coming to Malaysia - humanitarian work.

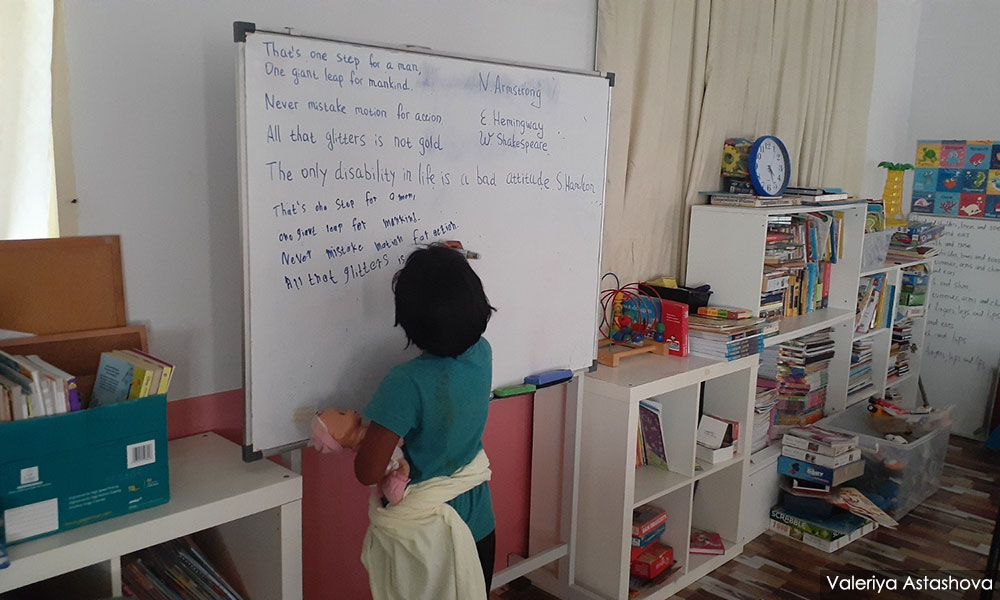

She joined a group of individuals distributing food supplies at the Pos Woh village in Tapah, Perak, and after speaking to the villagers, she offered to move there and teach full-time.

“I approached the village head and asked if he would be interested if I would come and conduct English classes.

“He was laughing at first, ‘look at you, living with Orang Asli, we have no air-conditioner’, but then he spoke to the mothers in the village, and they were really enthusiastic,” Astashova recalled.

Six months after she moved to Pos Woh, she said her students had made great progress with their English.

“When I first arrived, zero people spoke English. The lorry driver Mr Gopal (who transported all the donated study materials to the village) translated for one hour when we arrived. But then Mr Gopal was gone. No signal, no internet so I cannot even call to ask for a translation,” she said.

At first, she and the villagers mostly communicated through body language and hand gestures.

“But you know, in just two to three months, some of my students could speak and translate for me,” Astashova said proudly.

Two of her best students, Jenny and Safinah, 15 and 17 years old respectively, have improved so much that they are now her assistant teachers, she said.

Meanwhile, her 10-year-old son, who moved to the village with her, also quickly adapted to life in Pos Woh, she said.

“He was really struggling without internet and, of course, with the language barrier when he did not know anyone.

“And then, actually, he found out that there are other joys in life apart from the internet. He made friends very easily. There was no bullying because he was different. They invited him to go fishing, play football and swimming in the river.

“Kyri had his skateboard, so he taught them how to ride a skateboard… Then we got 10 skateboards donated and all the kids enjoy it very much.

“He actually misses his friends a lot right now,” Astashova said.

In the news again

The Russian recently made headlines again after the Department of Orang Asli Development (Jakoa) abruptly terminated her permit to conduct the programme in early March this year and instructed her to leave the village.

A few days ago, it was reported that Malaysian authorities would take “stern action” against her for allegedly continuing to collect donations for the Orang Asli community programme in Tapah, even though the programme had been cancelled.

Astashova has since denied all the allegations against her.

She and Kyri are now back in Kuala Lumpur, where she is trying to appeal to Prime Minister Muhyiddin Yassin to reconsider her permit so she can go back to teaching at Pos Woh.

Right now, her assistant teachers, Jenny and Safinah, have taken over teaching the classes and coordinating donations on the ground, but it is hard work for the two young girls, she said.

Not only that, Astashova is also determined to see her appeal succeed so she can freely visit the Pos Woh villagers whenever she wants.

“They love me and I love them, but we cannot see each other. They cannot leave Pos Woh because they do not have transportation and I cannot go there,” she said, adding that she had become very attached to her students after living with them for six months.

Since the news about the authorities planning to take “stern action” against her, she has received offers of help from kind individuals, including an offer to help get her home to Thailand.

But for now, she does not intend to go back to Thailand just yet.

“I still have 0.001 percent hope, so I still won’t give up on my appeal to the prime minister.

“And even if I go back home, it is only so I can keep appealing,” she said.

Malaysiakini has reached out to the Russian Embassy, which said that Astashova has not applied for consular support, but the embassy will continue to monitor the situation.

"The embassy sent a request to the Malaysian authorities for clarification. We follow the development of the situation with Valeriya Astashova," said a representative from the embassy. - Mkini

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.