HISTORY: TOLD AS IT IS | In August 1786, Francis Light acquired possession of Penang after signing a preliminary letter with Sultan Abdullah Mukarram Shah, the ruler of Kedah. This is something that most Malaysians are aware of. However, many people would be surprised to learn that he was a private trader before becoming a colonial official.

Many people are also aware that the Kedah sultan had to forego the island because he desperately required British assistance to protect Kedah's sovereignty from Siam, with whom Kedah was regarded as a vassal tenant. It is little known that Light's intimate knowledge of the Malay world, gained while he was a trader, allowed him to easily persuade the sultan to lease Penang.

This article aims to shed light on who these country traders were and the many roles they played.

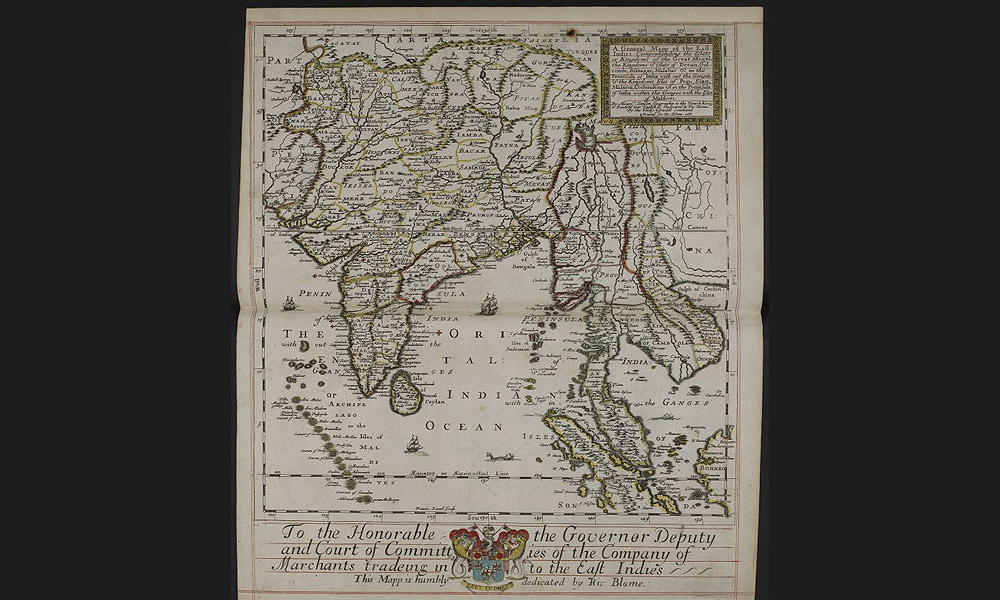

The country traders were British East India Company employees. They were tenacious traders who had a reputation for disobeying royal decrees banning them from trading on occasion. These traders endeavoured to trade in Asian waters, namely in India, the Malay Archipelago and China. The expansion in the activities of country traders in the Straits of Malacca began in the mid-1750s and became quite prominent by the mid-1770s.

It was estimated around 100 country traders operated in Southeast Asian waters between 1750 and 1820. On the Malay peninsula, they were active in five regions: the key ports around the Straits of Malacca such as Kedah, Aceh and Junk Ceylon (Ujung Salang); Pahang and Terengganu, particularly in 1719 and 1720; Johor; Selangor and Linggi in 1737; and Riau in the 1760s. James Scott, Thomas Forrest, and of course Francis Light, were among the well-known country traders of the 1770s and 1780s.

The country traders were the bearers of the English government's imperial ambitions. They accomplished this by forging trade ties with local dignitaries and establishing trading settlements along main routes. They dealt with the ‘saudagar raja’, a senior trade officer or royal merchant who was typically an Indian Muslim. Country tradesmen conversed in a vernacular Malay dialect. Notably, Francis Light could read and write standard Malay using the Jawi script. This unmistakably indicates that Malay was the archipelago's lingua franca.

The country traders needed to get along with the Malay rajas, be knowledgeable about the Malay trade, regulations and customs, be able to withstand the tropical conditions, and have a lot of patience. On numerous occasions, they were entrusted with delivering letters on behalf of the East India Company to Malay rulers. This task needed familiarity with Malay protocol and customs.

Owing to their grasp of the Malay world, they were able to ensure supply of economic resources, mainly tin, for Chinese and European markets by establishing good relationships with Malay elites. In the Malay ports, opium and cotton were sold, while products from the archipelago were traded in Canton.

Transformative role

The country traders had such strong relationships with local elites that they were invited to serve as advisors. On June 27, 1785, Sultan Ibrahim of Selangor, for example, reportedly enlisted the assistance of Francis Light to fly the British flag and requested the appointment of a Resident in his state so that he may freely trade with the Bugis. The sultan even made a special request for Light or Scott or Forrest to be appointed as administrator of Kuala Selangor.

Light had a significantly more transformative role in Penang. He persuaded Bengal's Acting Governor-General John Macpherson to take possession of Penang and develop it as an independent port. In his letter to Macpherson, he highlighted Penang's potential, claiming that it would attract Bugis, Chinese, and Malay traders and grow into a bustling entrepot.

Light also gave a complete description of the Malay states lying around Penang and it is produced in a letter to the Governor-General of India, Lord Cornwallis, dated Jan 7, 1789. This is not surprising, given his intimate ties with the rulers of the Malay states as a country trader.

It is possible that Light actually exaggerated Penang’s potential. In reality, his goal to seize Penang stemmed from a personal, imperialistic yearning. As a matter of fact, the East India Company did not pay him much for occupying the trading settlement for company traders. He admitted that he would have resigned if it were not for his partnership with James Scott.

Nevertheless, it was Light’s character of a zealous country trader that drove him to develop it as a free port, even without the Indian government’s permission. He envisioned the free port as an economic strategy to break the Dutch monopoly in the Straits of Malacca once and for all. It was also necessary to liberalise trade in Penang, which had previously been a dull market. The idea of free trade was welcomed by the Malay nobility.

Penang grew significantly, as expected. Its population grew to 1,000 individuals two years after its founding in 1786. By 1793, the population had grown to 5,000 people, and by 1804 it had grown to 12,000 people. Its population had grown fivefold between 1813 and 1825. In terms of exports and imports, the value was only $853,592 Spanish dollars in 1789, but it had climbed to $1,418,200 Spanish dollars by 1804.

Global capitalist economy

The Malay states were drawn into the global capitalist economy by English country traders. These traders did so, interestingly, not through coercion, but by arming themselves with knowledge of Malay economic and political affairs, mastering the Malay language, familiarising themselves with appropriate Malay etiquette, and having a firm grasp of the Malay archipelago’s geographical and nautical details.

They learned about local trade processes, including the types of commercial products, trading patterns, and local protocols. The knowledge was eventually beneficial to English officials, private merchants, and large trading enterprises that began arriving in Southeast Asia in the 19th century.

Their most significant contribution, however, was the introduction of free trade, commonly known as laissez-faire, which allowed the Malay states' economies to expand to a greater extent than they had previously. This provided the path for multicultural societies to emerge, as when Light implemented a liberal policy in Penang, he welcomed immigrants into the economy. The country traders appear to have also introduced Western capitalism, commercial agriculture, and new economic institutions, like banking services, to the country for the first time.

The presence of country traders may have also deterred a more aggressive type of British official intervention, since they made known how rich the Malay Archipelago could be, and instead demonstrated the success of treaty signing as the least expensive and profitable means to advance.

It is also possible that the Malay noble elites who built commercial ties with country traders were tactful rather than submissive. They were quick to notice that forging relationships with the English traders could in turn act as a political bulwark against their local rivals.

Granted, it would have opened the country up to more imperialistic activities in the future, but the point is that the Malay elites were quick to see the country traders as an ally when they first met them. They were, however, clever strategists, as indicated by the fact that they did not rely solely on the English to survive. Some of them even formed relationships with the Dutch while already having relationships with English country tradesmen.

To conclude, country traders undoubtedly played an integral role in the shaping of the economic history of the Malay Archipelago from the 17th to the 19th centuries. However, Malaysian history, it could be said, has not provided enough space for the role and importance of the country traders. - Mkini

SIVACHANDRALINGAM SUNDARA RAJA is an associate professor at the University of Malaya’s History Department. He is a well-known scholar in the field of Malaysian economic history, with numerous local and international research publications to his credit.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.