The most contested issue surrounding the GE15 electoral results is which coalition won the majority of Malay votes.

This final piece in the ethnic voting series, number seven, looks at Malay voting patterns in GE15. The focus is on Peninsular Malaysia, but the conclusion addresses the national Malay voting patterns including findings from Sabah and Sarawak, the subject of the two earlier pieces.

The analysis shows clearly that Perikatan Nasional (PN) won the most Malay support, as both Pakatan Harapan and Umno lost ground among Malays. The findings should not come as a surprise given the seat gains of both PAS and Bersatu, parties that won contests in Malay areas.

Please note that the finding of the microanalysis of polling stations varies only slightly from my earlier macro analysis last November, reaffirming that Malaysia is highly polarised and impactful swings took place among the Malay community in GE15.

The Malay Vote: Variation and rethinking interpretations

The analysis finds five important patterns:

First, there is considerable variation across states and seats in Malay support. The strength of different candidates/incumbency and control of state government did have an impact on Malay voting patterns. There is no one Malay pattern that evenly fits all of Malaysia.

Second, the Malay community remains divided. Voting patterns show that the Malay community is in fact many communities, an observation repeatedly advocated by scholars.

Historically, the Malay community has long been divided in elections and the GE15 results repeat this trend. What differs is the balance of votes among Malay parties has shifted.

Third, the swing in Malay support was equally the product of a decline in Harapan’s appeal among Malays and Umno’s collapse.

While most draw attention to “PAS” as a pull factor, a “green wave” in which the party is believed to be attracting conservative votes in a more conservative society, data shows that the push factor - the weaknesses of Harapan and Umno to appeal to Malay voters is as important.

PAS has long benefitted from its position in opposition, acting as a residual party that captures dissatisfaction. The Islamist party won over considerable dissatisfaction, which should be understood to be the product of both a push and pull dynamic.

The analysis suggests, at most, there was a limited “green wave” as the electoral swings among Malays were also tied to the varied appeals of other coalitions and parties beyond PAS.

Fourth, the analysis finds that different parties recorded different levels of support from Malay voters in GE15, but the variation is minimal among Harapan/Muda parties and more significant among those in PN.

Finally, of the two PN parties, PAS emphatically won more Malay support in the seats that they contested compared to Bersatu. This boost was especially concentrated where they held the state government.

Yet, of the two PN parties, Bersatu made similar gains, holding its own and reinforcing the view that there was indeed an “Abah” factor in GE15. Bersatu has emerged as a political national player in its own right, achieving what Dr Mahathir Mohamad – no longer its leader – wanted, displacing Umno (at least for now).

The Malay plurality: PN gains

Before detailing the results of the analysis, it is important to reiterate the caveats earlier. First, the findings are statistical estimates drawn from the polling station results. They speak to patterns rather than exact numbers.

Second, the elections were over four months ago. The GE15 voting estimates are not an indication of current support for different coalitions or the government now.

Let’s look at the results. PN won the majority of Malay voters in Peninsular Malaysia, an estimated 54 percent. This was followed by Umno at an estimated 32 percent. Harapan picked up the support of an estimated 13 percent of Malay voters in Peninsular Malaysia.

The variation among states is significant. PN performed extremely well among Malay voters in the states where it controls the government – Kedah an estimated 67 percent, Kelantan an estimated 66 percent and Terengganu an estimated 63 percent.

It is only in three states – Negeri Sembilan, Malacca and Johor that PN did not win the majority of Malay votes, in large part to the strength of Umno in these states.

Umno lost the mantle of winning a plurality of Malays. The party’s decline in support among Malay voters has been ongoing since 2008.

The party’s performance was weakest in Kedah, at an estimated 21 percent, followed by Perlis at an estimated 26 percent and Kelantan at an estimated 27 percent.

Umno held onto its core political base in Johor at an estimated 45 percent, Malacca at an estimated 43 percent, Negeri Sembilan at an estimated 45 percent and Pahang at an estimated 42 percent. It’s varied support among Malays is also tied to where the party has had a strong political base and controlled the state government (with the exception of Perlis).

The findings show that Umno remains strong in parts of the Malay heartland, although in almost all of the states, PN won higher support.

Harapan’s electoral support among Malay voters is the lowest in Peninsular Malaysia. It secured the highest support in the states where Harapan, specifically PKR, held the state government, Selangor an estimated 23 percent and Negeri Sembilan an estimated 19 percent.

Malay support was lower in Penang where the DAP has governed the state, at an estimated 12 percent. The lowest Malay support for Harapan was in Terengganu an estimated three percent, Kelantan an estimated six percent, Pahang an estimated eight percent and Kedah an estimated nine percent.

Erosion or gain of Malay support?

This variation across states is echoed among different seats, where candidates influenced support as well. Key leaders in Umno, for example, won higher Malay support than the party average, as is the case for party president Ahmad Zahid Hamidi in Bagan Datuk an estimated 53 percent and Johari Abdul Ghani in Titiwangsa an estimated 51 percent.

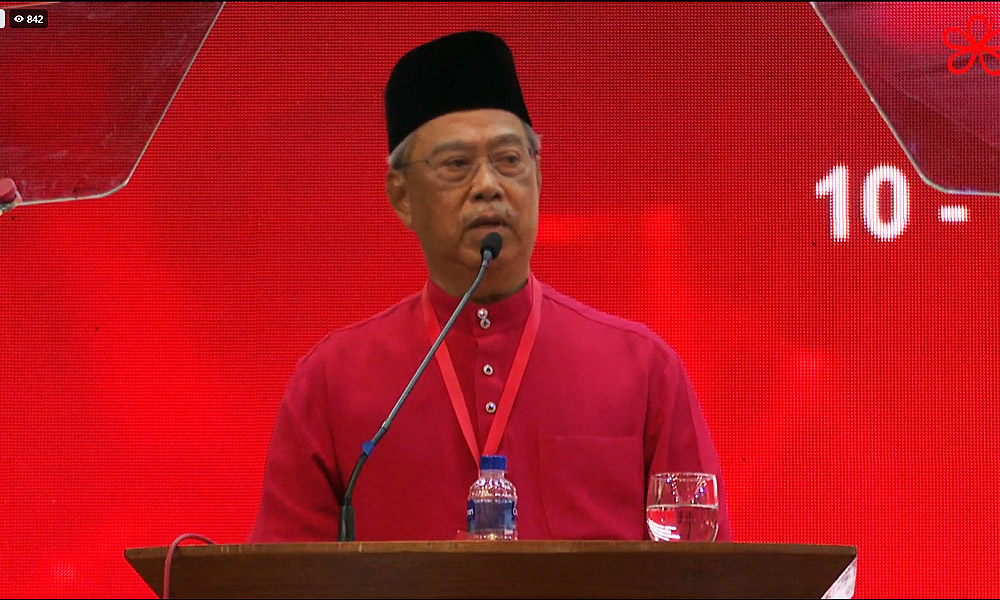

This is also the case for PN leaders, with Bersatu president Muhyiddin Yassin winning more Malay support in Pagoh at an estimated 63 percent.

The GE15 Malay swings from GE14 are not evenly distributed across coalitions and parties either. While support among new voters is important given the higher share of younger voters in the electorate (a theme that will follow in my next voting analytical series that looks at other socio-economic patterns), the data show that Harapan lost an estimated 11 percent of support among the Malay electorate, while Umno lost an estimated 12 percent, essentially the same share.

PN’s gains came equally from winning over voters of both Harapan and BN.

The variation is sharper among the different parties. DAP lost the most estimated support among Malays, 20 percent. Given the attacks on the party, which heightened from 2018-2020, this support erosion among the community should not have been unexpected.

PKR also lost ground, an estimated 16 percent, with Amanah losing an estimated 10 percent. The parties in Harapan and its ally Muda performed essentially similarly.

Amanah’s number is slightly lower due to its weak performance among Malays on the east coast of the peninsula. Yet, looking broadly at the overall party pattern in Peninsular Malaysia, the Harapan/Muda support levels are largely similar.

This is not the case for PN. PAS’ electoral support among Malay voters is the highest of the Malay parties, an estimated 59 percent, an estimated gain of 27 percent of Malay votes in the seats it contested.

Its PN partner, Bersatu won an estimated 48 percent of the Malay vote in the seats it contested, a gain of an estimated 28 percent. That both PN partners performed well among Malays speaks to the strength of their campaign, a campaign that was flush with resources.

Yet it also shows the importance of Bersatu in the coalition, where the “Abah factor” was a pull of support for many Malay voters. The findings show that Bersatu is an important party in its own right among the Malay community.

(Re)looking at the (limited) green wave

The ethnic voting results call for a rethink of what happened in GE15. I argue that both push and pull factors were at play. The assessment that GE15 was primarily a “green wave” is exaggerated.

First of all, GE15 results were shaped by racialised ethnoreligious narratives and attacks from 2018 onwards.

Harapan’s erosion in support was tied to these relentless attacks on the coalition after it won power. Even as Harapan parties effectively campaigned separately, as PKR ran its own separate campaign in the field, the coalitions and its allies performed similarly.

The use of themes of displacement, tapping into insecurity, was heightened in the GE15 campaign, bringing out Malay voters in the high turnout and contributing to PN’s gains of previous Harapan seats such as Kuantan and Permatang Pauh.

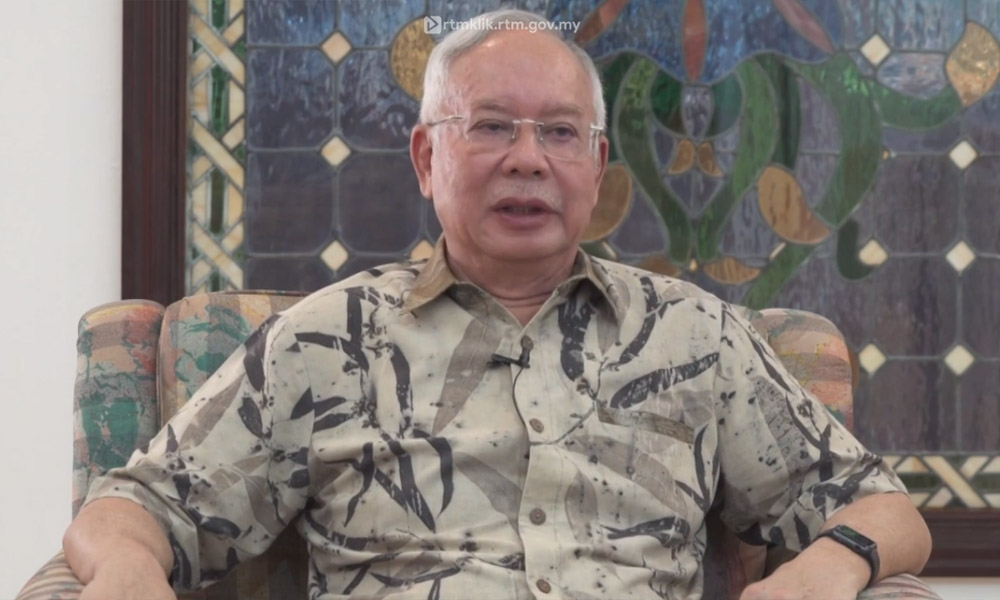

This aim to discredit Harapan’s representation of Malays was tied to the coordinated use of identity politics to win back power, with the irony that while Najib Abdul Razak’s Umno led the charge initially in 2018 - the electoral beneficiaries of this ethnoreligious racialised strategy were PAS and Bersatu.

It is not a coincidence that a similar pattern of racialised incidents and rhetoric is occurring again in this pre-state election period.

Second, the voting pattern of Malays is connected to Umno’s decline, its collapse in performance to 26 seats. This decline began well before GE15, yet decisions in the campaign by Zahid made it worse.

The most obvious indication of this is the shift in Perlis, Umno’s self-inflicted damage. The weaknesses of Umno in Kedah and Kelantan are telling as well with low Malay support, where internal party infighting and a lack of regeneration of leadership were evident.

Keep in mind half of the support gains to PN came at the expense of Umno’s performance in GE15. The other half came from Harapan.

Third, it is necessary to unpack PN’s support. PAS did make significant gains in seats and Malay vote share, so there is evidence of stronger “green” support. PAS won an estimated 11 percent more Malay support than Bersatu.

Yet the data shows that PAS support is strongest where it holds power at the state levels. PAS has used the resources at the state level to stay in power, in addition to the well-oiled resources of PN in GE15.

Victories in Terengganu and Kelantan pre-GE15 showcased how effective the party is in holding onto the governments and capitalising on electoral gains secured by allying itself to other parties.

While PAS’s contribution to PN’s gain should not be underestimated, the mobilisation of the electorate through appeals to conservative Muslim voters, its machinery, social networks and racialised rhetoric should not be seen as the only factor shaping the GE15 results.

Finally, given Bersatu’s strong performance, this party brought something to the campaign. It was not just money.

Harapan’s victory in 2018 was shaped by Mahathir. Similarly, PN’s victory in 2022 was shaped by the Muhyiddin “Abah” pull as well.

With the Sheraton Move, Bersatu undercut Umno’s Malay nationalist label, as Muhyiddin became associated with becoming the Malay “protector”, gaining support after the racialised narratives claimed that Malays were supposedly being displaced from power after Umno lost power in 2018.

Muhyiddin’s focus on the economy and social protections when he was prime minister also shored up his support among the Malay community hard hit by Covid-19.

In this regard, the results in GE15 were shaped by the governance and circumstances arising from the pandemic, which accentuated the hardships of many Malays and made the narratives of displacement more salient.

Divided and dynamic

The findings confirm that Malay politics remains highly competitive and changing. The swings in support in GE15 were shaped by conditions before the election and in the campaign itself.

Moving forward, the Malay vote will be further impacted by developments post-GE15 and the performance of the Anwar led-government.

While some reading this analysis may want to use this study’s findings to make claims of political legitimacy, this is a mistake. If anything, this series on ethnic voting in GE15 has reinforced that ethnic-based support among communities is dynamic, as Malays seek different representation to meet their needs and address their concerns.

Looking at Malay voting in Malaysia as a whole, including Borneo, – no one party controls a clear majority of Malay support.

As the two earlier pieces in parts 5 and 6 showed, the Malay vote in Sarawak and Sabah was won primarily by parties based in Borneo with Gabungan Parti Sarawak (GPS) winning an estimated 78 percent of Malay/Melanau support and various parties/coalitions in Sabah winning Malay support, namely Warisan an estimated 32 percent and Gabungan Rakyat Sabah (GRS)/BN winning an estimated 52 percent.

The Malay vote was divided in GE15. Nearly half of it was won nationally by PN, with majority support only from Peninsular Malaysia.

Importantly, Anwar’s government, with Umno, GPS, GRS, Warisan and Harapan collectively, won the support of the other half of the Malays. Unlike PN, Anwar’s government also won support from the other ethnic communities as well.

For all the coalitions, the findings show the need to strengthen support, to reach out across communities and, given differences among Malay voters in how they voted, within communities.

Here other lenses – generation voting, class differences, gender and urban-rural differences will offer insights. These lenses will be developed in further publications. For now, the main takeaways of national ethnic polarisation, multiple swings and an ethnically divided electorate stand out.

Thank you for reading this series, and to Malaysiakini for their hard work in editing and translating the articles in the search for a greater understanding of Malaysia’s changing politics. - Mkini

READ : GE15 ethnic voting analysis - Part 1: An introduction

READ : GE15 ethnic voting analysis - Part 2: Who voted?

READ : GE15 voting analysis - Part 3: Hidden, pivotal Indian swing

READ : GE15 voting analysis - Part 4: The Chinese Pole

READ : GE15 voting analysis - Part 5: Sarawak electoral swing

READ : GE15 voting analysis - Part 6: A Sabah mix

BRIDGET WELSH is an honorary research associate of the University of Nottingham, Malaysia’s Asia Research Institute (Unari). She is also a senior research associate at the Hu Fu Centre for East Asia Democratic Studies and a senior associate fellow of The Habibie Centre. Her writings can be found at bridgetwelsh.com.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of MMKtT.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.