Withdrawals by the prosecution and too many delays - these were some of the reasons why over half of the 28 corruption cases since 2018 involving 21 top politicians have fallen through.

A study by institutional reform group Projek Sama also found that the absence of a dedicated law to regulate political donations had caused some politicians, including a former minister, to be let off.

The study looked at 28 cases of corruption and related offences, such as money-laundering, involving 21 present and past MPs and state lawmakers. They dated back to 2018 when the first Pakatan Harapan government was elected on a promise of stamping out graft.

The 21 politicians include a former prime minister, a serving deputy prime minister, past ministers, and former heads of agencies and government-linked entities.

In the 28 cases, 10 were disposed of due to the Attorney-General’s Chambers withdrawing the charges at various stages of the proceedings, Projek Sama said.

“In these cases, the court’s role was limited to deciding whether to grant a discharge not amounting to acquittal (DNAA) or a discharge amounting to acquittal (DAA),” Projek Sama said.

“Three of the 10 withdrawals are legitimate on grounds of death, technical correction, and pre-trial payment of compound.”

A DAA for politicians accused of corruption, criminal breach of trust, and/or money laundering can be valid and legitimate after a proper trial, the group said.

“But DAA or DNAA caused by withdrawal of charges under Section 254 of the Criminal Procedure Code (CPC) or inordinate delay in prosecution or appeal by the AGC will erode public confidence.”

Of the 28 cases, nine are still ongoing at the trial stage, while two are at the Federal Court level.

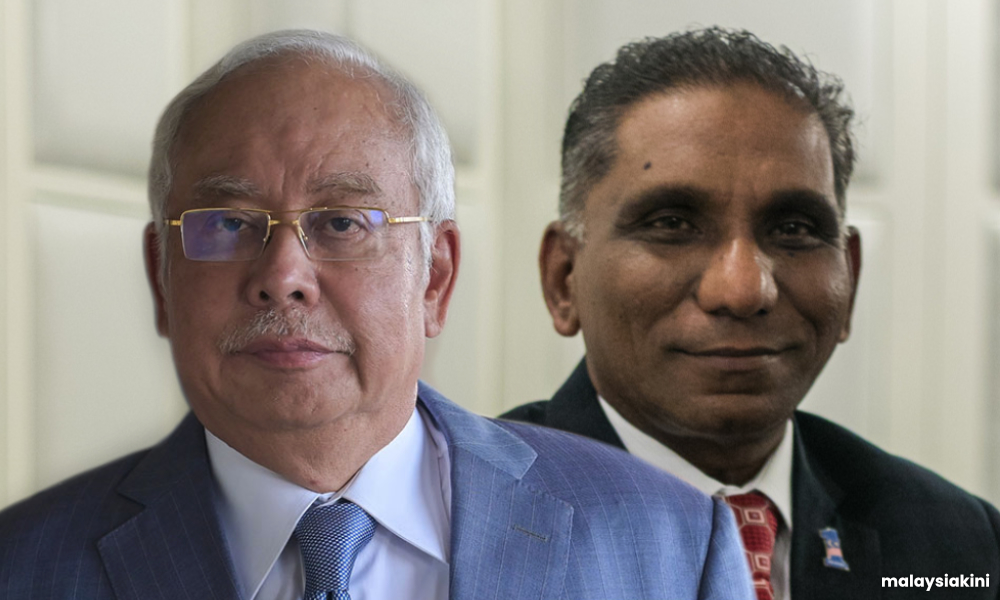

Only one - former premier Najib Abdul Razak’s SRC International case - ended with the individual behind bars.

Delays and suspicions

A sample of the cases showed how withdrawals and delays, complicated by the fused role of the AG and public prosecutor, led to a DAA or DNAA, Projek Sama said.

In another case involving Najib, the court granted him a DNAA due to excessive delays in the trial caused by the prosecution, Projek Sama said.

Najib and former Treasury secretary-general Irwan Serigar Abdullah were jointly charged with criminal breach of trust involving RM6.6 billion in payments to the International Petroleum Investment Company in 2018. They were then granted DNAAs on Nov 27 last year.

The delays were because the prosecution could not produce certain government documents, as they were classified under the Official Secrets Act, Projek Sama said.

“When high-profile corruption trials stretch across years without reaching verdicts - or worse, never commence at all - public perception of selective justice intensifies.

“The inability to bring cases to trial, regardless of the technical reasons, creates the impression that systemic obstacles conveniently emerge in politically sensitive prosecutions while other cases proceed smoothly,” the group added.

Meanwhile, Deputy Prime Minister Ahmad Zahid Hamidi’s DNAA in the Yayasan Akalbudi case, after the establishment of prima facie, sparked suspicions due to the timing and change in the attorney-general.

Zahid was charged with 47 counts of CBT in 2019 involving RM260,000 of Yayasan Akalbudi funds in his capacity as the foundation’s trustee.

He was ordered to defend himself against the charges in 2022, but was then granted a DNAA in 2023 after the prosecution withdrew all charges.

Donations and LoR

In three cases, Projek Sama found a troubling pattern in the use of Letters of Representation (LoRs) as the basis for prosecutorial withdrawals.

These were Zahid’s Yayasan Akal Budi case, former Penang chief minister Lim Guan Eng’s charge of buying a house at allegedly below the market price and Sabah governor Musa Aman’s corruption case.

“While LoRs are a legitimate mechanism allowing accused persons to present arguments for reconsideration of charges, their use in these cases raises significant concerns about transparency and accountability in prosecutorial decision-making”.

The case of former federal territories minister Tengku Adnan Tengku Mansor, meanwhile, illustrated the need for a political financing act, the group added.

Initially convicted and sentenced to 12 months in prison and a RM2 million fine, Tengku Adnan was eventually granted a DAA by the Court of Appeal on July 16, 2021.

According to previous reports, the majority opinion of the Court of Appeal was that the funds deposited into his account were a donation from an individual to fund Umno’s campaign in two by-elections.

Plugging the gaps

To solve these issues, Projek Sama proposed reforms that include enacting a political financing act to regulate donations to political parties.

“Such laws should clearly distinguish between legitimate political donations - which may appropriately be received by politicians or political parties… and criminal gratification that constitutes corruption,” the group said.

“Clear legal definitions and disclosure requirements would reduce grey areas that complicate both prosecutorial decisions and public assessment of politicians’ conduct.

The role of public prosecutor must also be separated from that of the attorney-general, as the fused role creates potential conflicts of interest.

“The AG serves as the government’s chief legal adviser while simultaneously exercising independent prosecutorial discretion. To address concerns about political influence and ensure prosecutorial independence, these roles must be separated”.

However, this separation must also be accompanied by an independent prosecutorial body that is accountable and free from political pressure and the government of the day, the group added.

Such reforms are necessary for the public to continue having faith in the justice system, the group added.

“Malaysians have been frustrated for decades by what many perceive as selective enforcement of law, particularly in politically sensitive cases, resulting in a “two-tiered” (dua darjat) society with different treatments for sharks (jerung) and anchovies (ikan bilis).

“The public perception is that politically connected offenders frequently escape conviction or serious punishment - not due to the merits of their cases, but because of their power, wealth, or political alignment with those in authority.” - Mkini

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.