It was not a case of the “dog ate my homework” or “my brother did it.”

When confronted with a simple question, the artful dodging in providing answers has found many defenders. It deserves to be a case study in political gymnastics.

For a government that promised to fight corruption and uphold the rule of law, it was pathetic watching its leaders bend backwards to “protect” the beleaguered MACC chief.

A Bloomberg report highlighted that as of January, Azam Baki owned 17.7 million shares in financial services company Velocity Capital Partner Berhad - which is about a 1.7 percent stake. He has since clarified that he sold them in July.

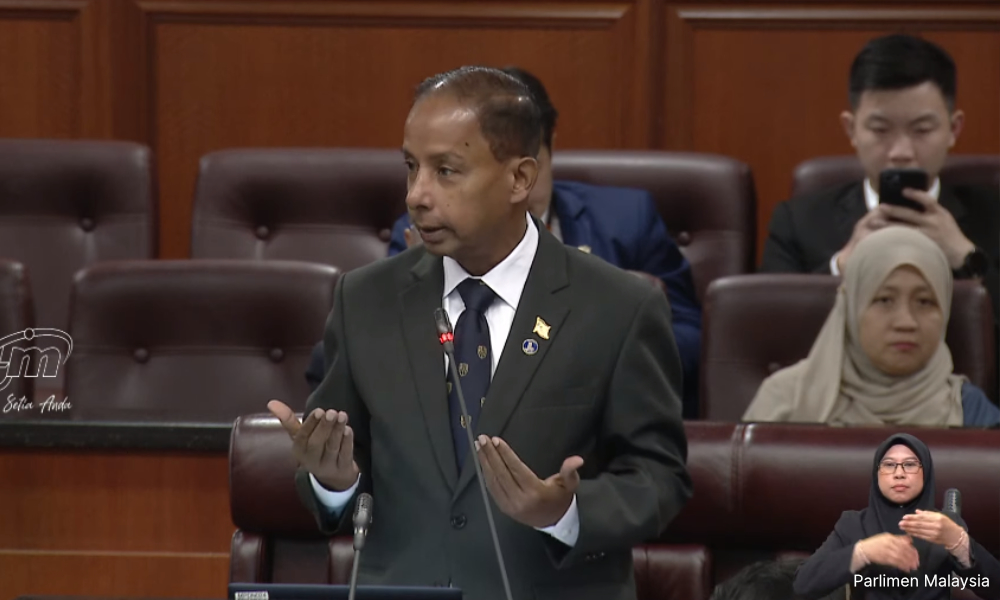

First came Deputy Minister in the Prime Minister’s Department (Law and Institutional Reform) M Kulasegaran, who erroneously claimed there were no regulations barring civil servants from holding shares above RM100,000.

He even insisted that Azam had informed the government about his shares in advance - only to backtrack upon discovering a 2024 government circular explicitly prohibiting civil servants from purchasing shares that exceed either five percent of paid-up capital or RM100,000 in current value.

For the record, the 2024 Public Officers’ Conduct and Disciplinary Management Circular, available on the Public Service Department’s website, makes this crystal clear.

Under Rule 17(b) of the circular, civil servants cannot purchase more than RM100,000 worth of shares in any single company - making Azam's holdings far in excess of the limit.

The shares are worth close to RM800,000 as of the opening of trade on Tuesday, far in excess of the limits placed on civil servants - they cannot buy more than RM100,000 worth of shares in any single company.

A broken system?

When a government that campaigns on integrity cannot answer a yes-or-no question about its own anti-corruption chief, the sickness is not in the critics but the system itself.

Following Bloomberg’s damning report, MACC hastily closed ranks around its chief, insisting that Azam had fully complied with asset declaration rules.

Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim soon joined the chorus, declaring there was no need to sack him: “Why should I sack someone who is doing their job?... Read his (Azam’s) explanation. This is a sickness.”

But one can read Azam’s statement repeatedly, and the core issue remains glaringly unanswered: Did he not breach government regulations on holding shares above the RM100,000 threshold?

Azam’s defence that he no longer holds shares, that his trading account is empty, and that all transactions were declared skirts the central question.

Regulations stipulate that officers cannot own more than five percent of a company’s paid-up capital or exceed RM100,000 in value. His claim that open-market purchases exempt him directly contradicts the circular.

Not the first time

This is not Azam’s first brush with controversy. In 2011, economist Edmund Terence Gomez resigned from MACC’s Consultation and Corruption Prevention Panel, citing disturbing questions about the “nexus between business and law enforcement.”

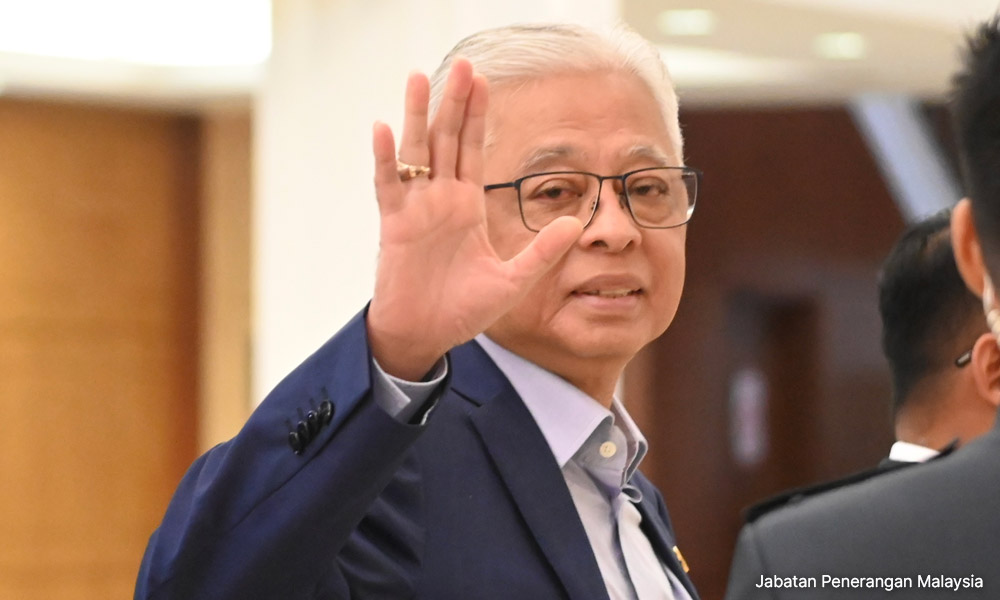

Azam’s defence then - that his brother used his trading account - was exposed as a lie when the Securities Commission found the trades were executed by Azam himself. Yet, he was “forgiven” by then-prime minister Ismail Sabri Yaakob.

But Anwar, then opposition leader, pledged to raise the matter with Ismail Sabri.

This was after PKR Youth handed him a memorandum, which, among others, called for MACC chiefs to declare their assets.

Since taking power as prime minister in November 2022, however, Anwar has become a staunch supporter of Azam, once declaring that the latter was the only one brave enough to go after corrupt leaders.

Now, history repeats itself. Having not learnt from past scandals, Azam once again dabbled in the share market - and once again, he has been caught with his pants down.

When the nation’s top anti-corruption enforcer bends the rules, and the government bends over backwards to shield him, the scandal is not Azam’s shares - it is the collapse of political will.

Integrity cannot be declared through the Human Resource Management Information System (HRMIS) forms or press conferences; it must be lived. And right now, Malaysia’s watchdog looks more like a lapdog.

The deeper tragedy is this: every time Azam wriggles out of accountability, the government signals to the public that rules are negotiable, that promises of reform are disposable, and that the fight against corruption is little more than theatre.

Each defence mounted for him erodes trust not only in MACC but in the very idea of clean governance.

Malaysia does not suffer from a shortage of regulations - it suffers from a lack of courage to enforce them.

Until leaders stop shielding compromised officials and start upholding the standards they preach, the rot will not be in one man’s share portfolio, but in the very foundations of public trust.

When the watchdog bites only at critics and never at corruption, the question is no longer whether Azam should go - it is whether Malaysia still has a watchdog at all. - Mkini

R NADESWARAN is a veteran journalist who strives to uphold the ethos of civil rights leader John Lewis: “When you see something that is not right, not fair, not just, you have to speak up. You have to say something; you have to do something.” Comments: citizen.nades22@gmail.com.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of MMKtT.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.