KINIGUIDE | The government’s recent announcement to abolish the death penalty with plans to replace it with at least a minimum of 30 years’ imprisonment has raised much debate among the public.

Families of murder victims have cried foul while human rights advocates laud the government’s move.

Article 5 of the Federal Constitution guarantees that no person may be deprived of life or personal liberty. This is an important reference, especially when it comes to punishing those who threaten social order or another person’s life.

However, the same article includes the phrase “except in accordance with law”. So, should the state be allowed to take someone's life in the name of justice? Where should the line be drawn?

The abolition of the death penalty would not only affect the 1,279 people on death row, but it also involves debates on the constitution, political system, philosophy and ethics.

Then there’s the question of whether Malaysia has the moral authority to fight for the lives of its citizens abroad, like in the case of 31-year-old Prabu Pathmanathan (photo), who was executed on Oct 26 in Singapore after failed attempts by various quarters to halt the punishment.

This first part of a series of four articles on the death penalty offers an overview of capital punishment in Malaysia and around the world.

1. What are crimes that carry the death sentence?

According to de facto Law Minister Liew Vui Keong, there are 32 sections in eight federal laws that provide for the death sentence for those convicted of the crimes they have been charged with.

The death sentence is mandatory for 12 of the sections, for crimes such as murder with intent to kill, drug trafficking and possession of firearms.

Mandatory death penalty means the judge can only sentence the accused to death upon conviction, even if the accused has a disability or a mental disorder.

For the remaining crimes, the punishment is at the judge’s discretion.

Section 277 of the Criminal Procedure Code (CPC) states: “When any person is sentenced to death, the sentence shall direct that he be hanged by the neck till he is dead, but shall not state the place where nor the time when the sentence is to be carried out.”

Nevertheless, there are two exceptions.

Section 275 of the CPC and Child Act 2001 (Section 97) stipulate that the death sentence is not allowed to be passed on a pregnant woman and children under the age of 18. They shall instead be sentenced to life in prison.

2. How many countries have abolished the death penalty?

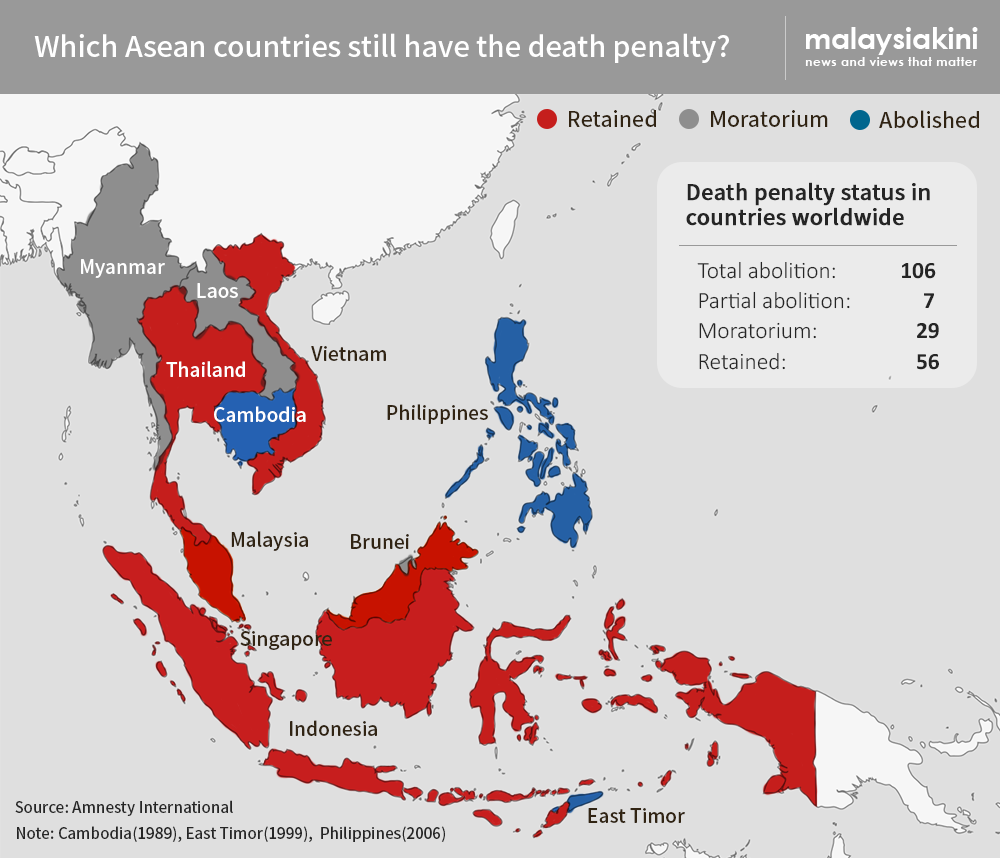

According to Amnesty International, there are 142 countries in the world that have abolished the death penalty or announced a moratorium while 56 countries still maintain it.

Of the 142 countries, 106 have totally abolished capital punishment, seven have partly abolished it while 29 have delayed the executions.

Malaysia is among the 56 countries that still carry out capital punishment, along with China, Jordan, Iran and Egypt, among others.

Among the 11 countries in Southeast Asia, six have abolished the death penalty or put executions on hold. They are Cambodia, Philippines, Laos, Brunei, East Timor and Myanmar.

The five that have yet to do so are Malaysia, Singapore, Indonesia, Vietnam and Thailand.

3. How many have been sentenced to death in Malaysia?

According to the Prison Department, there are 1,279 death row inmates among nearly 60,000 convicts as at Oct 11, 2018.

This number consists of 710 Malaysians and 569 foreigners, with 1,136 males and 143 females.

A total of 932 people were sentenced to death under Section 39B of the Dangerous Drugs Act 1952, while 317 people were convicted of murder.

Of this total, 366 are making an appeal, while another 355 are waiting for a pardon, which may or may not be granted by the Yang di-Pertuan Agong.

Based on parliamentary replies, 51.7 percent and 17.7 percent of death row inmates were convicted of drug trafficking (228) and murder (78) from 1960 to 2011. A total of 33 persons on the death row were executed from 2010 to 2018.

4. Can death penalty deter crime?

Death penalty advocates believe that capital punishment can deter crime, but how true is this?

Statistics from the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime show veal that the murder rate in the Philippines slightly decreased after the death penalty was abolished there in 2006. However, it increased after two years until 2011.

In Cambodia, where the death penalty was abolished in 1989, the murder rate progressively declined from 2003 to 2011.

However, in Thailand, which still has the death penalty, the murder rate had also gradually reduced from 2003 to 2015, while in Malaysia and Bangladesh, the murder rate fluctuated over the years.

Thus, there is no clear evidence that death penalty correlates to crime rate.

5. What has Malaysia done so far?

The new Pakatan Harapan government has listed the abolition of the death penalty as one of its promises in its 14th general election manifesto. It initially planned to abolish all regulations related to the mandatory death penalty only but it was later announced that the death penalty would be abolished and replaced with an imprisonment term of 30 years.

However, the plan to abolish capital punishment is not a new idea here in Malaysia.

The death penalty abolition movement has been a long-fought one by NGOs such as the Human Rights Commission of Malaysia (Suhakam), National Human Rights Society (Hakam), Malaysian Bar Council, Lawyers for Liberty, Amnesty International, Kuala Lumpur and Selangor Chinese Assembly Hall (KLSCAH) Civil Rights Committee and Malaysians Against Death Penalty & Torture (Madpet).

In 2009, at the United Nations Human Rights Council’s Universal Periodic Review, a Malaysian representative said that the government intends to amend existing drug-trafficking laws to replace the mandatory death penalty with life imprisonment, and to review all regulations related to capital punishment.

After a four-year struggle against his death sentence, Malaysian Yong Vui Kong was given the chance to have his death sentence replaced with life imprisonment in a rare decision by the Singapore High Court in July 2010. His change in fortune may be linked to Singapore legal reform and also the collective effort of Malaysian and Singaporean activists, as well as the intervention from then-Foreign Affairs minister Anifah Aman to seek clemency from the Singapore president.

In 2011, under the leadership of then-de facto law minister Nazri Abdul Aziz, a cross-party parliamentary roundtable in 2011 passed a few resolutions, including that the government should abolish the mandatory death penalty, especially for Section 39B of the Dangerous Drug Act 1952. It should also declare a moratorium to suspend the execution of inmates currently on death row while reviewing the laws.

Last year, the BN government tabled an amendment to remove the mandatory sentence for convictions under Section 39B of the Dangerous Drugs Act 1952, giving courts the full discretion to mete out life sentences against drug traffickers. The Dewan Rakyat passedthe bill on Nov 30, 2017.

Last month, the Harapan government announced a moratorium on all death sentences pending amendments to the legislation.

6. What are the basic arguments of pro- and anti-death penalty groups?

Some death penalty advocates insist that capital punishment serves as justice for victims and their families. They also believe that it would deter crime.

There is also the argument that life imprisonment incurs a huge cost compared to the death penalty and that the government should prioritise human rights and compensation for innocent victims over that of death row inmates.

Meanwhile, those who are against capital punishment argue that the miscarriage of justice could happen during police investigations or the prosecution process.

Unlike prison sentences, absolute judgments may lead to people paying for crimes they did not commit, in which case the death penalty is too absolute and irreversible.

-KiniGuide

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.