As the dust settles over the Kimanis by-election, it is valuable to look at the voting patterns that secured the Umno victory in this competitive seat and to flesh out the broader political implications of this outcome.

The voting shows that even in a locally-driven contest, which this by-election was, the erosion of Pakatan Harapan and its allies’ support is taking on a now familiar form – the decline is broad, across races and generations. Voters who are disappointed with a perceived lack of reform and weak economic performance are willing to return to Umno and simultaneously send a signal to those in office that they are not doing enough to hold onto their GE14 political mandate.

The Warisan loss in Kimanis – the fifth loss by Harapan and its allies in the 10 post-GE14 by-elections – only ratchets up the pressure for Harapan and Warisan to deliver and transform how they engage the electorate.

Make no mistake, this loss was one of their own making. The Kimanis outcome has given a new lease of life to Umno and nationally puts the party on a stronger footing in its relationship with PAS and as a viable opposition to win government in the next election. Within Sabah, the Umno victory adds to the fluidity and competitiveness of state politics while simultaneously highlighting the greater saliency of using divisive ethnic issues to win (and lose) support.

Machinery and mobilisation

The analysis of voting below is drawn from statistical estimates of voting behaviour at the polling station level in the Jan 18 by-election, focusing on the two socio-economic cleavages that were most prominent – ethnicity and generational differences.

Overall voter turnout reached 76 percent in the election, speaking to a high level of voter mobilisation. Both Umno and Warisan heavily used resources and deployed their machinery to bring out their supporters.

Of the two campaigns, Umno’s was stronger as the party has adopted a new campaign organisation since Tanjung Piai, rejuvenating their electoral machinery and allowing for more effective deployment of their resources. This level of turnout is high compared to other by-elections in East Malaysia, but a drop from the 86 percent turnout of GE14.

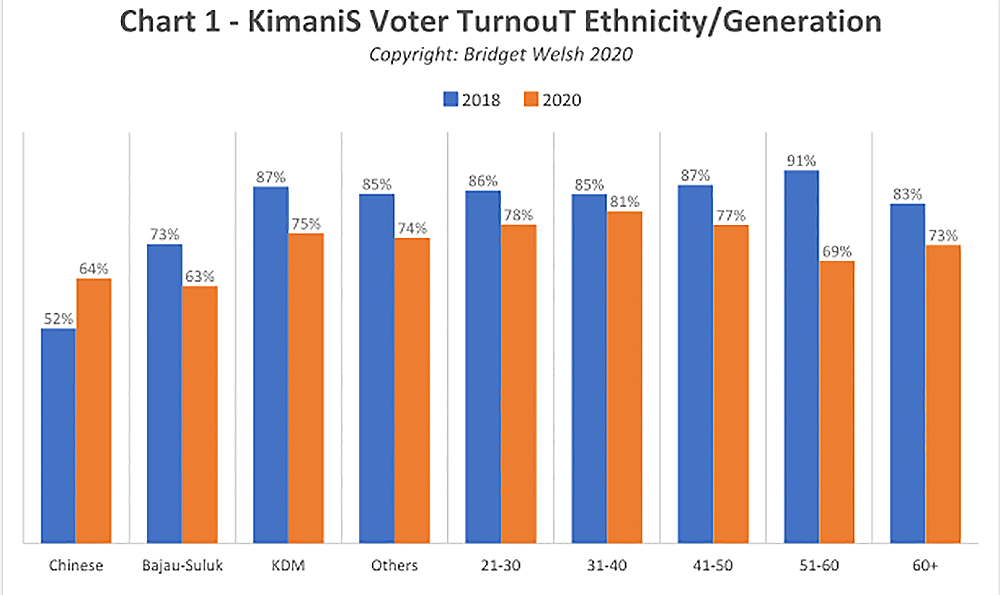

As Chart 1 below shows, voter turnout levels declined across all the age cohorts and all ethnic communities, except the Chinese (who at less than 5 percent comprise a small share of the electorate).

The increase among the Chinese voters (12 percent estimate) was among the highest shifts, with the other major ethnic shift occurring among Kadazandusun Murut communities (KDM) (12 percent estimate), a similar decline. As will be seen below, Chinese voters did not change their support patterns significantly, but KDM did so, with their first sign of discontent being staying home in larger numbers.

The most important finding in turnout levels is an estimated 22 percent drop in the 51 to 60-year-old cohort. This group – which I have pointed out were socialised in the reformasi era and have strong reform orientations in survey research – did not come out to vote.

This is a pattern that has become common in the last few by-elections nationally. It speaks to the fact that a large share of the base of Harapan and its allies are no longer supporting them. Without the issues of 1MDB and negative sentiment towards Abdul Najib Razak (and the Aman family), as well as a perceived failure to implement reforms and distinguish themselves as different from the previous government in terms of patronage and practices, large numbers of this group did not come to the polls.

Ethnic and generation Swings

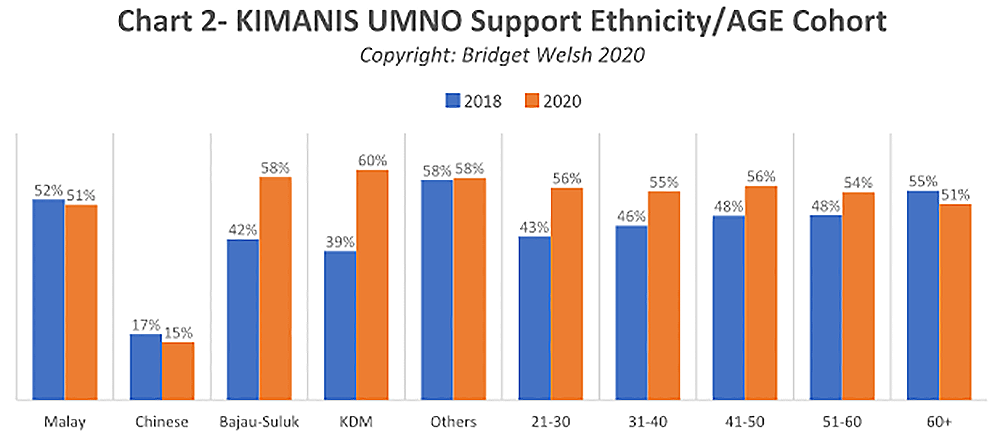

Interestingly, as shown in Chart 2, those in this group that did come to the polls, however, voted for Warisan in higher numbers by a modest estimated increase of 6 percent, showing that even if they are unhappy with Warisan/Harapan, they could not support Umno.

Where Umno was able to capture the most support across generations was among voters under 30, winning an additional estimated 12 percent of this cohort. The decline in support among younger voters for Warisan/Harapan is also a national trend and speaks particularly to concerns over economic performance, as bread-and-butter issues are especially prioritised among this group. It is important to note that the decline in support was across all age cohorts, except older voters above 60, which remained loyal to Warisan in slightly greater numbers, an estimated 3 percent gain.

This starkest change in ethnic voting was among the KDM communities, an estimated shift in support of 21 percent toward Umno. The central role that the Sabah Temporary Pass (PSS) played in the campaign, tapping into emotive identity politics of displacement and representation, was crucial in this change.

It is no wonder the Warisan government has already announced a relook at the policy, as it was decisive in the outcome as ethnic sentiments were harnessed locally to feed discontent. The decline in representation of the KDM community by Warisan, however, is broader than the policy itself and calls for a rethink of how Warisan includes this community and addresses their concerns. The level of the ethnic swing speaks to the increased saliency of ethnic political mobilisation not only in Sabah, but nationally.

Another important finding across ethnic lines is the estimated 14 percent gain in support among Bajau-Suluk communities for Umno. These communities are seen as the ethnic core of Warisan and the shift shows that they are also unhappy with the state government. The PSS issue stirred up insecurities across communities, including those who were seen to gain from the measure.

There was also intensive mobilisation of this community by the Bersatu machinery, as the Shafie-Aman rivalry percolated in the campaign and worked against Warisan. Bersatu locally was seen by some to be more aligned to the Aman family rather than working to support Shafie and Warisan. The now Bersatu’s Membakut state seat (one of two state seats in the Kimanis parliamentary constituency) is held by Musa Aman’s son-in-law, Mohd Arifin Arif.

The by-election results at the polling station level reveal that the entry of Bersatu into Sabah has negatively impacted Warisan, as Mahathir’s goal to create a rival to Umno in Sabah has ironically empowered Umno. Internal differences within Harapan and its allies shape electoral outcomes.

A final observation on the voting behaviour is that the stability of the split in the Malay community. Primarily Bruneian Malays, the community divided their vote, supporting BN in an estimated slight majority of 51 percent as Warisan’s candidate Karim Bujang maintained the party’s support levels but was not able to dent the core Malay support that has been tied to Umno (and the Aman family) for the past two decades.

Notably, however, there was not a shift towards Umno among Malays in this by-election (which bucks national trends of movement from Harapan among Malays) and which points to continued divisions among this community in Sabah moving forward. Local Malay identities remain important in Sabah and this fragmentation is likely to continue.

Key takeaways

In looking at the by-election as a whole, the most decisive changes in support were along ethnic lines tied to the PSS issue, leading to declines of the KDM and Bajau-Sulok communities support for Warisan/Harapan.

Identity politics continues to predominate post-GE14 electoral outcomes. Umno has proved itself effective in tapping into ethnic insecurities, as Warisan/ Harapan have shown their inabilities to redress concerns and engage the concerns of different communities effectively.

Second is the increasing abandonment of younger voters from Warisan/Harapan. Impatient younger voters want deliverables.

Third, there is the disenchantment with the reform-minded voters who do not want Umno to revive but are choosing to stay home as they no longer have faith in bringing about change. Kimanis shows this extends to the state level as well.

Finally, campaigns do matter. Warisan/Harapan have not substantively changed how they engage voters and still operate without adequate coordination and planning. The changes they have adopted are following the Umno mould, where they are not as competitive without the same level of machinery to carry out the campaign.

They are not adapting successfully to the new post-GE14 environment. Umno, in contrast, is doing so in its messaging and machinery.

Umno revival and Warisan/Harapan reality

For Warisan, beyond the call for reform, the by-election is a wake-up call at the state level that its engagement across communities is not working. The Aman family, through its ties to Bersatu and Umno, is still a major political force.

Despite the mass defections last year and charges against the state leaders, Umno is still an important player in Sabah. Its candidate, Mohamad Alamin, as a young, experienced leader, has the opportunity to lead the regeneration of the party in the state, as new alliances and relationships are likely to continue in the fluid transforming politics at the state level.

Nationally, the Kimanis by-election significantly strengthens the party’s position as a leading national opposition actor. Notably, this victory did not come from PAS support. It was tied to the mobilisation of Umno’s traditional support base. This victory in Sabah also bolsters Umno on the national stage, as it can deliver support from a state that is crucial for winning national government.

The party is still dependent on others, but it comes out of Kimanis in a sweeter political position. Moving forward, this outcome may in fact enhance increasing pressures within Umno to avoid backdoor dealing and be more demanding in its relations with political allies. These issues will feed into internal differences about the party’s direction but cannot take away the reality that the party is powerfully remerging on the national stage.

Warisan was over-confident – as Harapan was in other by-elections. While acknowledging the negative impact of PSS and Mahathir’s leadership at this juncture among Sabah voters, it is too simple to blame this outcome on specific individuals or policies.

Both Warisan and Harapan have failed to transform their own engagement with the electorate, following old models of using resources and stale issues. As a whole, these parties do not have the machinery of Umno (or PAS) and lack issues to mobilise voters. In fact, the weaknesses in performance in government is the main issue.

More than ever, the Kimanis outcome highlights the need for Warisan and Harapan to bring about meaningful reforms, reduce internal bickering and to re-evaluate how they engage and communicate with voters given that they cannot compete with parties that have stronger grassroots organisations.

Once again, voters showed that if parties behave like Umno, then they might as well vote for Umno. Now in 2020, the iconic year, it remains to be seen whether Harapan leaders will show vision and let voters know that they are listening to their discontent by making substantive changes in their leadership and governance.

BRIDGET WELSH is a Senior Research Associate at the Hu Feng Centre for East Asia Democratic Studies, a Senior Associate Fellow of The Habibie Centre, and a University Fellow of Charles Darwin University. She recently became an Honorary Research Associate of the University of Nottingham, Malaysia's Asia Research Institute (UNARI) based in Kuala Lumpur. - Mkini

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.