QUESTION TIME | The wisdom of the decision to extend the Plus toll concession by a further 20 years is dubious, given the length of time it spans - now 38 years instead of 18 years. This is in return for an 18 percent reduction in toll and no further increases in toll charges up to expiry.

Given that many things can change over a period of 40 years, including whether cars, trucks and buses would even be a main mode of transport, such an arrangement, which must necessarily be made on current assumptions, could be fatally flawed in the future and produce adverse results for all parties.

But the eventual decision by the government to keep Plus with Khazanah Nasional (51 percent) and the Employees Provident Fund (EPF) (49 percent) is the right one. This was in large part due to the top executives of the two bodies insisting they will do what is best for their organisations.

Leaving that aside for the time being before we come back to it later, let’s look at the toll extension and its implications and the reasons that the government came to this rather dubious arrangement, which implies a hazardous far away look at the future - no looking glass, however sophisticated, can do that.

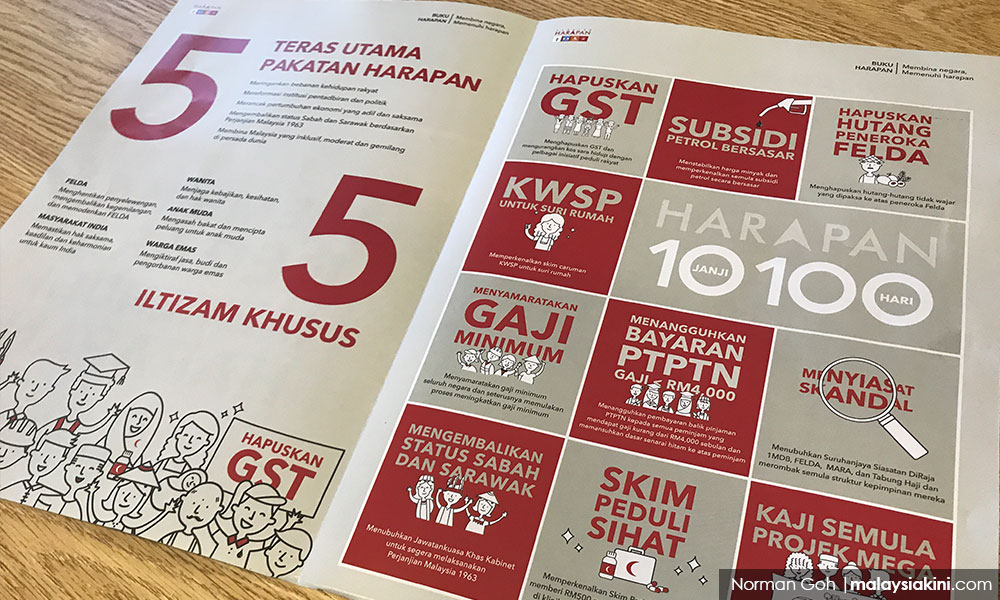

The reason that such a ridiculous proposition - the 38-year wait for the expiry of tolls - was agreed upon is the government’s, and particularly Finance Minister Lim Guan Eng’s excessive, shortsighted and needless fixation on reducing or even removing tolls as part of the Pakatan Harapan manifesto promise.

But really, this together with the abolition of the goods and services tax (GST) are two manifesto items that Lim and company should have given up. If they had, considerable effort and much money could have even been saved.

Predictably, Lim laid the blame on Harapan’s inability to abolish tolls squarely on the previous government, including 1MDB, and now says the government will save RM42 billion from not subsidising tolls.

One way out of this is simply to allow the agreed toll increases instead of that 18 percent decrease, and stop all tolls whenever they expire, which in the case of Plus would be 2038 instead of 2058. Then there will be no burden on the government.

In any case, who are the people paying tolls? Yes, those driving cars, all of who pay uniform charges no matter what car they drive. Thus, the poor who ride motorcycles or use public transport do not benefit at all from this 18 percent reduction in tolls. The higher income group largely benefits.

This is the same with that GST abolition - the previous government had exempted more than 200 vital items from GST. Thus the abolition of GST benefited mainly those in the middle class and above.

Lim talks glibly about that RM42 billion that the government saves over 18 years if they subsidise toll rates which they do not need to do. But what if GST was in place? Based on current collections foregone of RM22 billion a year, that would amount to RM396 billion over 18 years. Think of what the government can do with all that money if channelled into the right areas.

But perhaps the most important lesson is that those entrusted with taking good care of public funds and government companies must stand their ground when politically inspired moves threaten to undermine their organisations.

In this instance, their insistence on doing good by their organisations and combined courage in sticking to their guns while under pressure to give up their stakes will eventually result in them getting the maximum benefit for their organisations.

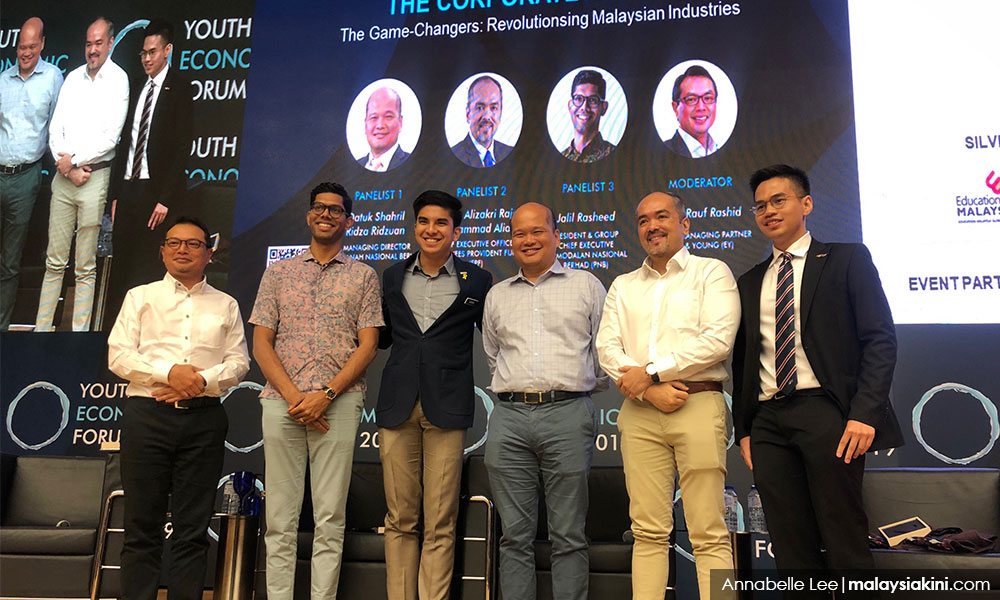

There are two names in this case - Khazanah CEO Shahril Ridza Ridzuan (third right) and EPF CEO Tunku Alizakri Alias (second right) who were appointed to their current positions in August 2018 following a change of heads at key government funds.

Shahril, who was then CEO of EPF, was picked to head Khazanah whose entire board resigned after its then managing director Azman Mokhtar failed to get a meeting with Prime Minister Dr Mahathir Mohamad. Shahril’s then-deputy Tunku Alizakri moved up to the top position at EPF.

The changes followed after Mahathir inexplicably criticised Khazanah for deviating from the policy of helping bumiputeras.

"But along the way, Khazanah decided it should take all the shares for itself and if they are good shares, well why not acquire the shares at the time of listing when the price of shares was very low and so they forget entirely about holding the shares for the bumiputera.

"They decided that they should be holding the shares forever as a part of the government companies owned by the government," Mahathir was quoted as saying.

However, Khazanah has no such explicitly stated mission or objective.

“We achieve our mandate by pursuing two investment objectives – commercial and strategic. The commercial objective focuses on achieving optimal risk-adjusted returns, to grow financial assets and diversify revenue sources for the nation. The strategic objective is to undertake strategic investments with long-term economic benefits for Malaysia or Malaysians, including holding strategic national assets.

“Khazanah’s mandate is to grow Malaysia’s long-term wealth. Grow in this context is to sustainably increase the value of investments while safeguarding financial capital injected into the fund. Long-term refers to a period spanning generations and focuses on ensuring future generations’ ability to meet their needs. Wealth refers to the value of Khazanah’s financial assets and economic development outcomes for the nation.”

The biggest target for the redistribution of this wealth out of Khazanah was of course Plus, with an overall worth of RM30-40 billion, inclusive of debt. Four private sector bids emerged, all of which could be traced to those who have or have had links with Mahathir and his trusted lieutenant Daim Zainuddin.

Shahril’s response to the four offers was very clear - they were all unsolicited offers and they were all too low. Therefore Khazanah was not interested in selling. Over at EPF, Tunku Alizakri stated unambiguously that his and the board’s sole objective at EPF was to safeguard the interests of its millions of members, mostly Malaysian workers.

But that did not stop those unsolicited offers which went through Works Minister Baru Bian. But when the decision came, Khazanah and EPF had their way. Without Khazanah and EPF endorsing the deal, the government would not have been able to proceed. The recalcitrant two would have to be removed first and perhaps the boards of the two organisations as well.

One hopes that this victory for the two will encourage other funds and government-linked companies to take similar strong and principled stances when it comes to sales of their assets to others - make sure the value is right, otherwise dig into the trenches and fight.

P GUNASEGARAM is editor-in-chief of Focus Malaysia. He says those in positions of trust must exercise the power they have for the benefit of the organisations they represent - no one else. - Mkini

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.