I begin my writing here with an apology to all close friends, friends, relatives and all Malaysian citizens who have placed high hopes on Maszlee Malik when he was the education minister, and on his team on Level 18 at the Education Minister’s Office, since about 20 months ago.

For many among them, I have yet been able to pick up the telephone; reply WhatsApp messages; process requests for their children to enter boarding schools; or process school transfer requests from teachers.

Twenty months is too short a time to fulfil everyone’s hopes.

I would also like to apologise to the many analysts who put the blame on the media team working at the minister’s office for not providing enough information. For sure the blame is on my shoulders as the press secretary to the minister, even if I only assumed the role in February 2019.

I think we tried our best, especially as the Education Ministry had become a target of attacks every hour, if not every day.

In the week before Maszlee announced he was returning his position, (former prime minister) Najib Razak had launched 34 attacks on Maszlee on his Facebook page.

This means there were almost five postings a day by Najib, focused on Maszlee alone.

What is education?

Several days before Maszlee made his announcement, I had gone to my office with a trolley bag to bring home my books. A small group of colleagues and I had already known about the issue then.

While packing up, I looked at all my books before placing them in the bag. One of the books was Paulo Freire’s seminal work - Pedagogy of Solidarity.

In the first few paragraphs, Freire presents three questions:

“What is education?”

“What can be done with education?”

“What is the basis for the practice of education as understood by us and human beings?”

These three questions are very inter-connected, but I was more drawn to the first question as it reminded me of the version of education found in the country. Or to be more specific, what is understood about the word “education” by people like Siti Kasim? (above)

Cultural imperialism

That first question from Freire is interesting because, before starting work at the Education Minister’s Office, I was a teacher and founder of an NGO.

As a teacher, I came from a teacher’s training institute and taught at a national school before starting classes and a school for needy children through my NGO. Then, I sometimes thought that I had gone through what was meant by “education”.

But in fact, we forget that internet speed at the 10,208 schools nationwide is still four megabytes per second (Mbps) compared to the Unifi Turbo 100 Mbps enjoyed by those who live at the MK28 condominium in Mont Kiara or the luxury condominium The Estate in Bangsar.

Our children in schools are at an internet speed deficit of -96 Mbps.

Or do we forget that there are uncompleted computer labs at schools in Sabah, even though they began construction in 2003, back when it was announced that science and mathematics would be taught in English (PPSMI)? Or that there are uncompleted and rundown 1,216 science labs across the country?

What is more heartbreaking is we forget that a large part of schools in Sabah and Sarawak remain rundown. In this case, what does “education” mean, as Freire asked?

Internet speeds at these schools are very slow. Computer and science labs are insufficient, and a big part of them are incomplete. These schools remain in the “rundown” category.

So, what is the type of education do we want to give our children?

An exporter of dreams

Freire also writes that education ought not to be implemented by force. If it is forced upon people, it will not be “education” anymore, but cultural imperialism.

What is sad is we can’t even discuss the cultural imperialism, as described by Freire, because the system we have today has yet to even attain the minimum or most basic status - which is to provide basic infrastructure.

Without an internet connection suitable for smartphone apps or 4G, how are we supposed to expect teachers to prepare our children to face the Fourth Industrial Revolution?

Without fully-equipped computer and science labs, how are supposed to expect teachers to emphasise science, technology, engineering and mathematics (Stem) at schools?

Without tables, chairs and classrooms suited for 2020 that are on par with schools in Putrajaya and Bangsar; how are children in Sarawak supposed to study?

Later in his book, Freire talked about how “we can’t export dreams”.

'Selective perception' by the Bangsar Bubble

This prompted me to ask if Siti Kasim understood Freire’s questions as mentioned above.

- Does she know how fast the Internet speed is across the country?

- Has she ever spoken to teachers who teach at government schools to understand the problems of Science labs?

- Has she ever been to rundown schools in Sabah and Sarawak?

If she is not able to answer these questions, what is the meaning of “education” as she understands it?

This is also why when (Penang Deputy Chief Minister II) P Ramasamy (above) said a few days ago that the changes implemented by Maszlee when he was education minister in the past 20 months were too small and minor, I saw a similar pattern between Ramasamy and Siti Kasim.

They are both surrounded by their own “bubbles” and only fraternise with elite political and corporate circles. They have never left the Klang Valley or Penang; never paid a visit to Orang Asli schools; never spoken to parents from families with disabled children (OKU); and never had access to B40 families. They only sit in their Bangsar bubble and they are actually a group that is removed from the majority of society.

Therefore, their idea of “education” is elitist and only ever discussed in famous hotels. Their ideas are extreme and not based on ground realities.

Please prove to me how are we supposed to formulate a policy to raise the (standards) of Stem when Internet speeds at schools are slow and science labs continue to be incomplete?

What is worse, the experiences of those in this Bangsar bubble sometimes come from “selective perception”. Recently, a veteran politikus was very upset at the national education system after a grandchild came from school and recounted a lesson from an ustazah (religious teacher) about “alam kubur” (the afterlife).

What?

419,904 agents of change

This is why when Maszlee first began as the education minister, the three taglines he introduced were love, respect and happiness.

This is because we believe that only through the introduction of these values could we convince teachers and utilise 419,904 of them as agents of change in schools.

All irrelevant tasks that teachers had were abolished. Dominant teacher groups like the National Union of the Teaching Profession (NUTP) were approached.

Issues faced by teachers like transfers were discussed. Teachers were presented as community heroes once more. We empowered the Program Adiwira Guru and Program Nadi Guru programmes.

Young teachers across the country who excelled at teaching were introduced to the public. Were these policies too academic? No.

The proof is that teachers cried when Maszlee left. This is because the policy implemented by Maszlee and the ministry in the past 20 months had applied theories and concepts from Paulo Freire’s Pedagogy of Solidarity.

Last night, a friend asked me, while we were at the mamak joint Restoran Syed in Lucky Garden, Bangsar: “The burden of proof is not with the ministry but actually with the government. What has the government given to the rakyat in the past 20 months?”

I could not answer.

The reason I have written about my thoughts here is really to ask “Siti Kasim and the gang”: What actually do they understand about the word ‘education’?

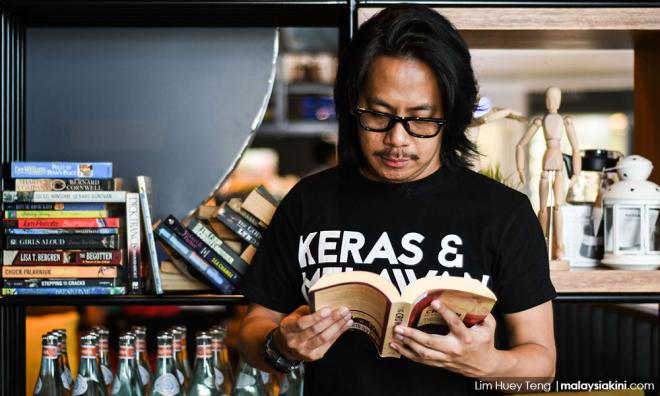

ZF ZAMIR (photo at top) was the former press secretary to Maszlee Malik, who recently resigned as education minister.

This is a translation by Malaysiakini of Zamir’s comment piece that was originally written in Bahasa Malaysia. - Mkini

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.