With the lockdown extended at least through mid-April, the impact will be devastating for vulnerable families, with serious short- and long-term effects for the economy and the society itself. One positive in the past week has been the ongoing constructive discussion about how Malaysia can get through this unprecedented trying period. This article joins the debate.

My earlier piece highlighted how society can work together and pointed out ways to harness social capital to strengthen ties and build social trust. This was based on the premise that the empowerment of ordinary people can make a difference – as it has repeatedly in Malaysian history – and that rebuilding ties is essential for the human spirit in these uncertain times.

Here I focus on a set of modest ideas for consideration, appreciating that the focus should not be on one side or another of the political divide, but bringing the best that can be brought to a difficult situation.

From the onset, I firmly believe that Malaysia has comparatively taken bold moves to address the crisis, not least of which was the needed extension of the movement control order. The Covid-19 crisis can offer further opportunities to move the country forward, to engage in needed reforms and to learn lessons on how to improve governance. A reform agenda has long been ignored and Malaysia is now, in part, facing the consequence of that neglect. Initiating reforms will not be easy but embracing different practices and policies can offer more protection.

That said, there will inevitably be serious losses, not just to lives, but to businesses and even to some sectors of the economy. On a personal level, we will lose friends and family in this period, and the hardships people will experience will be intense on many levels. The frustration has the potential to boil over along already frayed racialised lines.

Now more than ever, there is a need to look to the lessons from other crises, reach out and to assess the viability of other policies adopted elsewhere for Malaysia. Here are three areas of suggestions, focusing on governance issues that can protect Malaysians:

Improving crisis communication

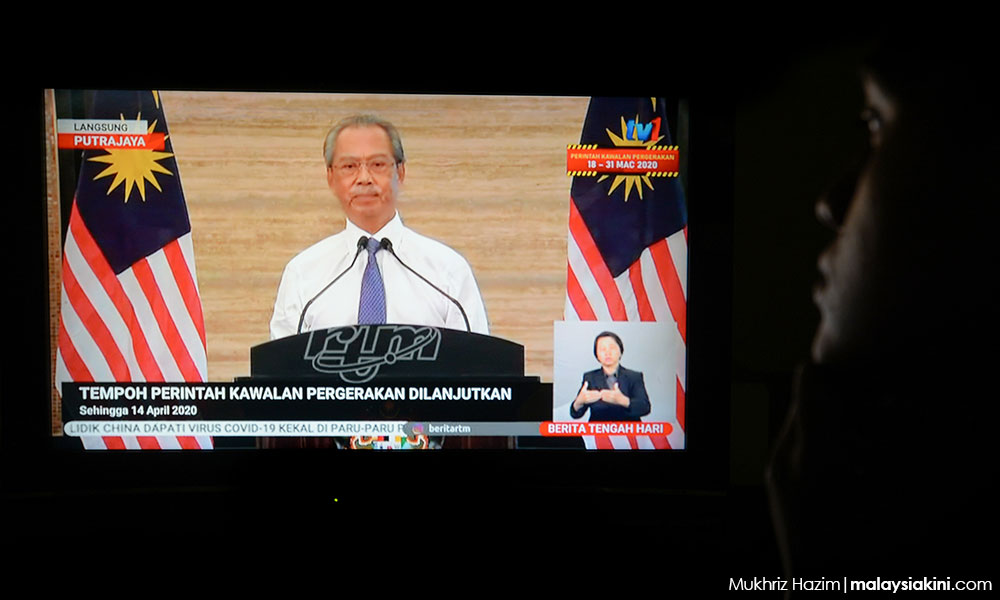

To date, the communication from the government has been a stream of ministers, including the prime minister, making announcements. These are followed up with SMS messages of key points. Muhyiddin’s down-to-earth style has been effective in reaching many communities, especially those in the Malay heartland.

The government’s communication needs to be further streamlined to avoid contradictory instructions and comments that erode public confidence (a.k.a. drinking warm water to stop Covid-19). We know from mistakes being made elsewhere – not least with what is happening in the United States – that a crisis should not be the opportunity for using the podium for posturing, but rather for clear and consistent messaging.

Routine reports are needed, for the information they contain as well as for the reassurances they provide (as best they can, given the difficult news). The director-general of the Health Ministry, Dr Noor Hisham Abdullah, should be commended for his professionalism and transparency. He serves as a role model for others.

Given Malaysia’s diversity, messages involving the public as a whole should be in multiple languages, even if the speeches themselves are in the national language. This can extend the reach, especially for the large number of migrant workers. Their health affects others, given that they are on the frontline of many essential services. Measures to assure that migrants have healthcare for Covid-19 have been positive, but more outreach in different languages can increase effectiveness.

It is also important to keep in mind that many Malaysians, notably in Sarawak and Sabah, do not speak Malay and inclusiveness can go a long way towards bringing the country together at this difficult time.

Greater consideration should be given to the tone of the messages. While orders are necessary, greater assurances and understanding of how different people will receive instructions should be considered. At a time of crisis, compassion is an integral part. Messages based on respect for the public are more effective. There have been significant improvements in providing information about helplines, including for mental health, but these can be extended, using alternative mediums.

Smart politics

The petty politicking needs to stop, from denying allowances and removing GLC boards to give away positions to continued backdoor meetings to wooing support of leaders and personal attacks. It has been bad enough that political jockeying and opportunism led to a change of government during a pandemic. There needs to be greater cooperation with states – all of them – and those that do not have a proper government, e.g. Perak, should make the appointments to positions. The time will come for a return to competitive politics, but it is not now, as cooperation is urgently needed.

Within Perikatan Nasional, serious consideration should be done to assess ministers that are not performing or do not have the right skill set for their position and replacing them. This is not about individual egos, but about the country. This is not a time for mistakes. At the same time, opposition parties could consider setting up a shadow cabinet, or clusters of members who are willing to work toward offering ideas and monitoring responses in key sectors.

In a crisis, best practice shows that those who reach out for help emerge stronger. There is so much talent in Malaysia who can serve through their expertise in healthcare, technology, science and in management of the economy.

The government could set up bi-partisan groups comprised of technocrats/business professionals to seek expertise on the complex issues the country is facing. Many of the country’s universities have talented specialists who should be included in developing solutions – especially in areas of technology and science. Groups are providing feedback informally, but more outreach and public illustration of this outreach is a sign of strength.

Right now, as in all crises, the dominant mode has been reactive, but ahead as the crisis deepens, more long-term thought will need to be given to proactive policies for recovery. The government needs inputs from experts in different fields, including civil society. A critical group that should be included is the private sector, who are most familiar with challenges to supply chains.

Crises are often unfortunately opportunities for further graft. Given the long history of corruption in Malaysia, in setting up programmes, adequate checks need to be put in place to assure that the crisis does not become an opportunity to line pockets. The practice of padding margins with kickbacks by suppliers needs to be minimised – not just in face masks. Civil society and the media will be watching, but leadership on these matters can be set from the top. Supplies need to reach those who need them.

Priorities and social safety nets

Debate has already centred on the various solutions to address those facing hardship. Focus is on two main initiatives to manage the shocks – social assistance and employment retention.

To start with, it needs to be recognised that Malaysia is in a difficult revenue position tied to the losses from graft, notably 1MDB, and reduction of GST which undercut available funds further. New taxes and levies cannot be introduced at this time. Ultimately, Malaysia will have to borrow funds to meet the needs ahead and try to do so on as favourable terms as possible. With low global interest rates, the current international context is a good time to borrow, with a range of options from different international financial institutions (IMF, ADB, World Bank) to the market.

To date, the two stimuli packages have primarily reallocated funds rather than tapped new spending, with the exception of additional costs of healthcare - costs which will increase further. Expectations for support need to be tempered with a realistic appreciation of the financial constraints the government faces.

In all measures, there will inevitably be prioritisation. The allocations should be needs-based, as a failure in inclusion will spill over into tensions in society. The face of poverty, loss and hardship is the same across communities.

Attention will have to be on the right timing to implement programmes to maximise their impact. Past practice has shown that cash transfers such at BSH (formerly BR1M) are spent quickly and do not last beyond a month. It would be a mistake to think this crisis will be over quickly, so some funds should be kept in reserve to manage coming shocks.

We have learned from other crises that in implementing social assistance, an analysis of how people spend their money is useful. Globally, experts are currently asking whether the funds will actually be able to stimulate the economy in this period of lockdown, so care should be taken to spread out relief measures.

Given the new context of lockdown, new ideas can be adopted for the implementation of programmes. Announcements of funds deposited in accounts, for example, could lead to a run to the banks and worsen health effects, contributing to a longer lockdown period.

This happened earlier with the lack of coordination between universities and the police over the lockdown. Bank personnel are already on the frontline. Forging a partnership with groceries in the form of cash vouchers could help to keep some social distancing in place. Collaborating to develop IT applications to manage funds would further potentially reduce risks.

The moratorium on loans and credit cards is a good initiative to date, yet this does not include those who are in the informal sector and do not have credit cards. Clarity on whether interest payments will be exempt during the six-month period would be helpful. Some banks, such as HSBC, have waived interest in this period and offer more protection to clients.

In contrast, the initiative offering RM500 withdrawals from the EPF funds has not gone down well, as it has been seen cynically as the government furthering the burden on people. It illustrates the need to have a more inclusive stimulus, one in which the government considers a range of measures – believed to be coming this week. One measure being used is tax rebates on business and individuals, which could offer relief, as well as delays in the payment schedule.

Now is the opportunity to forge stronger partnerships with the private sector. While Malaysia may not be able to afford the salary payments adopted elsewhere, there are opportunities to work with companies to keep employees employed – many of whom are working in safe social distance environments, safer than those at home. Rethinking how a lockdown can include employment in safe environments will be critical for Malaysia’s economic recovery. This period is also an excellent time for training programmes – which can be subsidised and operated from home, to allow for job transition and skill development.

Studies by the Malaysian Institute of Economic Research (MIER) are already pointing to a potential loss of two million jobs, with others pointing to higher figures if these numbers include the service sectors. Labour markets in Malaysia are fragmented and heavily dependent on cheap migrant labour. The crisis offers an opportunity to evaluate the effectiveness of past policies and to move towards new policies that reduce that dependence.

The focus of crisis management has rightly centred on health, security and livelihoods. One other area needs greater protection – the telecommunications sector. Along with water, electricity and food, the provision of the internet/social media in businesses and for individuals has become a lifeline in this period of increased isolation and uncertainty. This area is an arena for subsidies, as well as an opportunity for the strengthening of the infrastructure.

While Malaysians understandably expect more from their government and deserve more, Malaysia compares favourably to many responses elsewhere. More, however, can be done – a critical part is generating ideas and stimulating discussion. Malaysia’s greatest asset remains its people and these suggestions were written with this in mind.

BRIDGET WELSH is a Senior Research Associate at the Hu Feng Centre for East Asia Democratic Studies, a Senior Associate Fellow of The Habibie Centre, and a University Fellow of Charles Darwin University. She currently is an Honorary Research Associate of the University of Nottingham, Malaysia's Asia Research Institute (Unari) based in Kuala Lumpur. - Mkini

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.