The results from Johor polls are in and Umno/BN has won over two-thirds of the seats, with the opposition politically marginalised in the Johor state assembly.

As the analysis of the results has started, the debate has focused on the fact that Umno/BN only managed to secure 43 percent of the overall vote in its decisive return to government. This outcome is common in first-past-the-post electoral systems, which favour those that win a plurality of votes in particular seats and exclude the representation of alternatives.

The discussion has, however, opened up the questions, whether Umno/BN has in fact increased its support and whether its victory was the product of opposition division rather than the strength of its own support. Has Umno returned to electoral safety?

A preliminary look at voting patterns comparing the Johor 2022 polls to the state results in 2018 – vote share, seat results, ethnic voting and turnout patterns, and turnout in seats - shows that Umno/BN gained support overall and among different communities, but not as much as the overall results would suggest.

What is striking about the Umno/BN results is their consistency with the past. The Umno-dominant coalition won back the traditional party faithful, but did not return to its previous vote share even to 2013 levels (54 percent).

The main findings from the preliminary analysis, however, are within the opposition, with Harapan losing support badly across different communities. The preliminary findings show erosion of support across parties and communities for Harapan. Its support level is nowhere near levels of the past.

In contrast, Perikatan Nasional held onto its support. In fact, there were gains for PN across different communities.

No Umno/BN landslide, but Harapan erosion

Let’s take each of these initial preliminary findings one-by-one, starting with vote share.

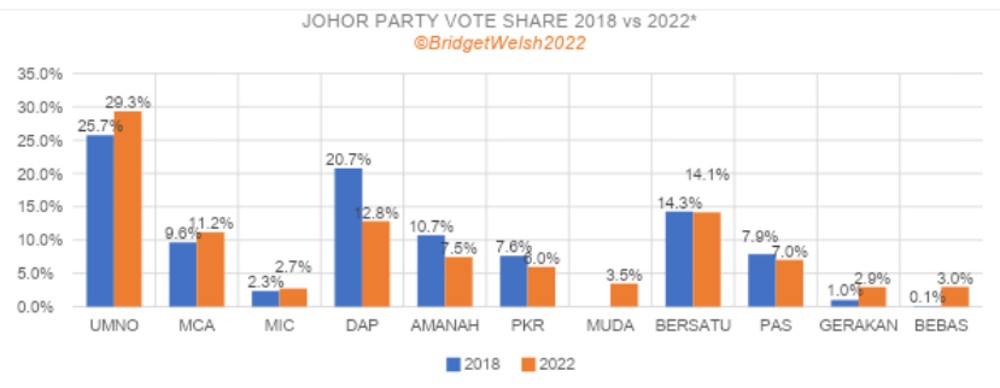

All of the BN parties gained in vote share, with Umno gaining 3.6 percent of the vote, MCA 1.6 percent and MIC, a marginal, 0.4 percent. Low, these vote share gains are not in line with a “landslide” victory.

They do show, however, that BN’s victory was across parties, and that the long defeated coalition in which both MIC and MCA have four seats has been electorally resuscitated.

Umno would not have the 2/3rds majority without its election partners, whose outreach to Chinese and Indian Johoreans was critical for the outcome.

Bersatu and PAS effectively held onto their vote share from 2018, with PAS actually losing a marginal 0.9 percent in the recent polls even as it picked up the seat of Maharani in a competitive contest. Still four-year loser Gerakan gained 1.9 percent of the vote.

The PN coalition came second in 25 seats significantly cutting into the previous support levels of Harapan. This was evident in seats like Parit Yaani, lost by Amanah by 294 votes.

To understand the electoral impact of PN in the race, in 35 out of 56 seats, the combined vote share of PN and Harapan was bigger than that of Umno/BN’s. The “landslide” victor clearly benefitted from a split opposition.

Yet the defeat was also the product of the opposition itself, notably Harapan. DAP lost the largest vote share, 7.9 percent, followed by Amanah 2.5 percent and PKR 1.6 percent.

Voters were not happy with their performance while leading the state and federal governments. Even popular hardworking incumbents such as Amanah’s Zulkifli Ahmad (former assemblyperson, not the health minister) in Kota Iskandar was ousted.

The drop in margins for the DAP seats that were won speak for themselves. For example, the “safe” seat of Johor Jaya's majority dropped to 1,922 from 15,965 in 2018.

PKR on its part performed badly in most of its seats, losing deposits and only scraping through in the one seat it won, Bukit Batu. This erosion speaks to the serious problems with Harapan's ability to garner political support under its current leadership.

The only bright spot was their loose alliance with Muda, which won 3.5 percent of the total vote competing in only seven seats, with inroads in urban and rural areas and importantly, across ethnic communities. Without the young party’s presence in the campaign, Harapan’s overall vote would have decreased further.

All Johoreans swing: Ethnic voting changes

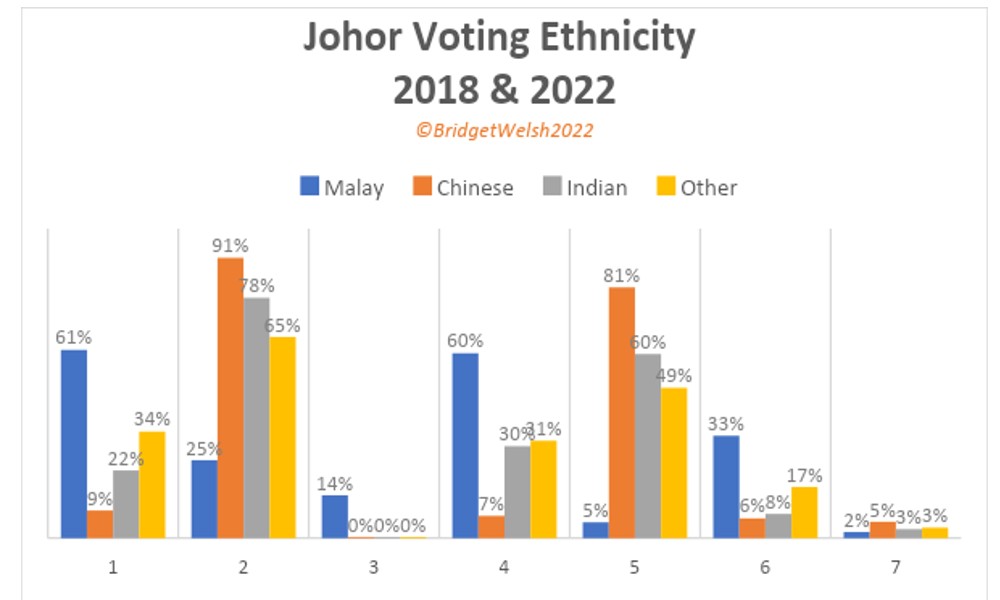

The reality of Harapan’s losses become clearly looking at the macro estimates of ethnic voting. (Please note these are preliminary estimates to be reviewed further at the polling station levels).

Harapan’s ethnic support dropped across all communities. The most apparent is the estimated 20 percent drop in Malay support, a testimony to the failure of Harapan’s leadership of Anwar Ibrahim, in particular, to win over Malay Johoreans.

Yet, there is also a drop in support among Indians of an estimated 18 percent and 14 percent among others, notably Sarawakians and Sabahans in Johor.

The Chinese support for Harapan dropped by an estimated 10 percent, repeating the weaknesses for the DAP that was also evident in Sarawak polls among Chinese voters. Harapan lost support across all ethnic communities in Johor.

By way of contrast, Umno/BN only gained in one community, Indians, by a margin of an estimated 8 percent. In reinforcing the consistency of current Umno/BN support with the past, winning only its usual supporters, there was little change among Malay support, Chinese support (2 percent estimated drop) and other ethnic communities.

Where the gains were made across ethnic communities was in PN. PN more than doubled its support among Malays, capturing an estimated third (33 percent) of this community in Johor. As argued earlier, PN is challenging Umno among the Malay electorate.

PN also picked up support among Indians, an estimated 8 percent, Chinese, an estimated 6 percent, and others, an estimated 17 percent.

The impact of resources and social assistance programmes was especially impactful in the outreach – but what comes out of the election is a stronger multi-ethnic showing for the PN coalition, yet one that does not win enough Chinese and Indian support to win seats in the multi-ethnic seats that comprise Johor’s assembly – or most of the seats nationally as well.

Staying Home: Turnout drop

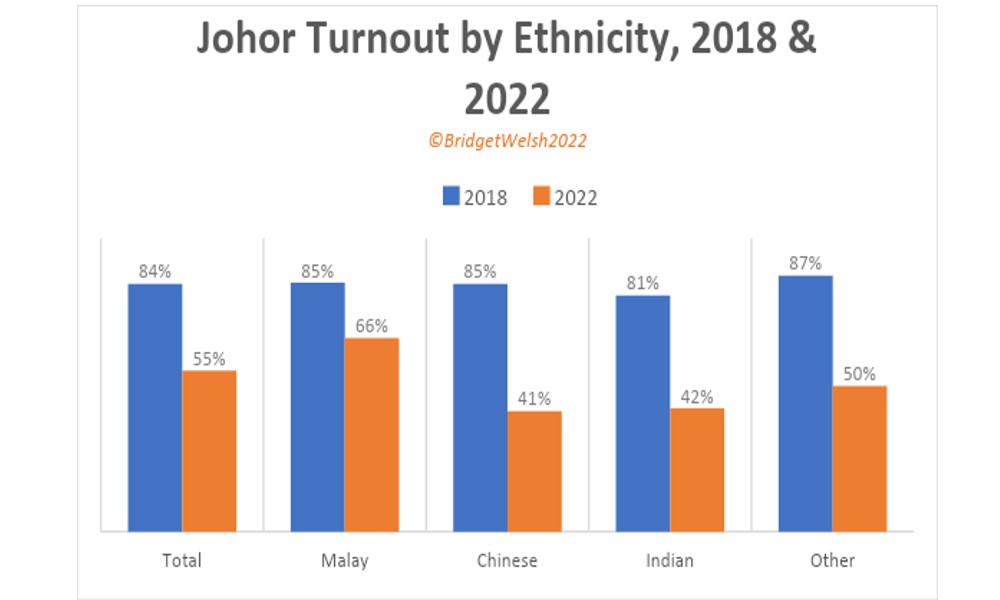

Compared to GE14, there was a drop in turnout of 29 percent, from 84.5 percent to 54.9 percent.

As this is calculated by overall share and this includes new voters and those who have automatically registered, a drop was expected. This was especially the case due to the difficulties of voters coming back from Singapore during Covid.

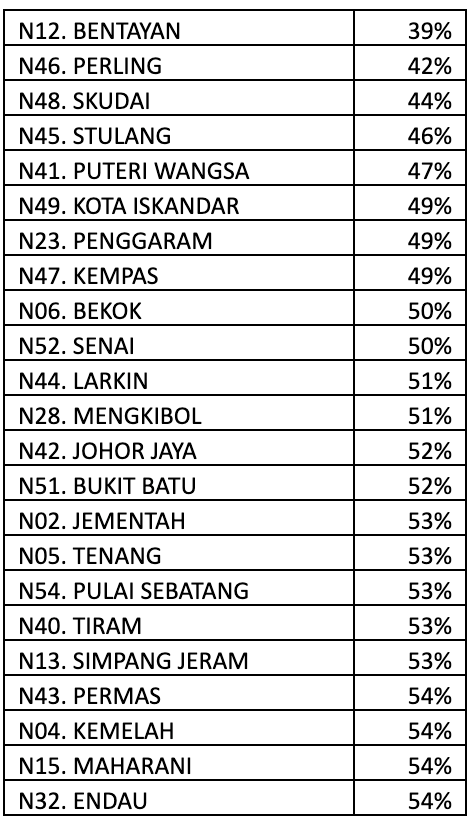

The impact of the Singapore border is evident in voter turnout drop. Over half the seats, such as Perling and Skudai to Tiram, are in the south and were affected by many voters working in the Red Dot.

Yet, there was also a drop in turnout around/in Muar such as in Bentayan, Simpang Jeram and Maharani, and in more remote seats such as Tenang and Endau. Many outstation voters did not come back.

Seats Lowest Voter Turnout Drop Johor 2022

The lacklustre campaign, Covid-19 and high costs of travel impacted the Johor election.

The results in quite a few of these seats were affected by turnout, such as Kota Iskandar and Bukit Batu.

Rural areas, especially in Felda communities, saw higher turnout levels; Sedili had 66 percent, with Sri Medan 67 percent, but these levels are far below turnout of the past.

The turnout drop was concentrated among Chinese and Indian communities, estimated at 43 percent and 39 percent decline respectively.

The drop among others was estimated at 27 percent, and among Malay Johoreans at 19 percent.

This across the board ethnic drop is now a common pattern in state-only polls, but turnout drop among voters that usually voted for Harapan in the past had a political impact.

While future analysis will look at the impact of other socio-economic cleavages using polling station data, on the ground discussions in Muar on election day suggested older and younger cohorts both opted to stay home.

Covid-19 was cited for older voters, with younger voters pointing to work obligations as well as discontent with all on offer.

To appreciate how important the drop in turnout is, one only needs to look at the seat results. Fifteen seats were won with a low margin of less than 10 percent.

Four seats were won with a margin of less than 500 votes: Bukit Batu (137), Bukit Pasir (198), Parit Yaani (294) and, Tangkak (372).

The seat-by-seat results were closer than the overall “landslide” results would suggest.

Changing fortunes

Overall, the results show that Johor was a highly competitive election and politics within the state, and by extension nationally, are far from stable. The swings in voting patterns show an electorate engaged with changes taking place, even if that choice is to disengage.

Turnout will continue to shape outcomes, and the lower turnout overall benefitted Umno/BN as they had better machinery on the ground to bring out their supporters.

The results show, however, that Umno/BN did not win over many new supporters. As Umno/BN calls for an early general election, they should take stock that their political base is not increasing.

In fact, their support is stagnant and still at a comparatively low level historically in Johor, far below it was before 2018. In particular, they are not gaining meaningful Malay support.

Umno/BN are reliant on a divided opposition to win, and, in the case of Harapan, a poorly performing coalition losing support.

They are also counting on the opposition – PN and Harapan – not being able to cross the ethnic divide to garner strong support across communities and to continue to avoid the repeated electoral calls for a leadership change. Of the two opposition coalitions, Harapan is by far in the most electoral difficulties.

The changes in ethnic voting and vote share show, however, that voters are watching, reacting and shifting to what is on offer, especially what is “new” – as shown by the gains of Muda electorally and persistent strength of PN.

Umno/BN was able to reverse its electoral fortunes in a short period.

The situation is not one where Umno/BN has returned to the political safety of the past, as the situation remains competitive and fluid. - Mkini

BRIDGET WELSH is a senior research associate at the Hu Fu Centre for East Asia Democratic Studies and a senior associate fellow of The Habibie Centre. She currently is an honorary research associate of the University of Nottingham, Malaysia's Asia Research Institute (Unari) based in Kuala Lumpur. She tweets at @dririshsea.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of MMKtT.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.