The Johor polls was the first time Undi18 voters were able to participate. Throughout the campaign, attention centred on their mobilisation and participation, compounded by the excitement generated with the maiden entry of Muda.

How did the youth vote? For that matter, how did other age cohorts participate in the election?

With data from over half of the seats (32) and nearly two-thirds (63 percent) of the overall polling stations, this analysis looks at generational voting in the Johor 2022 state election.

It begins with the usual caveats, the need to appreciate that the findings by age cohorts are statistical estimates drawn from a robust and representative, but not a fully comprehensive, sample of the results.

The findings confirm broader voting trends emerging in voting after the 14th general election (GE14).

These include a strengthening of Perikatan Nasional (PN) among the young, an erosion of support for Pakatan Harapan by those who voted for the coalition in 2018, less partisan loyalty among younger voters, dissatisfaction of the youth with the Anwar Ibrahim-led coalition, and a persistent dependence of Umno/BN on the support of older voters.

A generational lens in understanding voting in Johor shows how Malaysia’s political landscape is becoming more competitive and uncertain.

As young people in greater numbers who are included in the electoral roll gain more power electorally, they are bringing with them greater electoral volatility and uncertainty in electoral outcomes.

Cross-generation disengagement

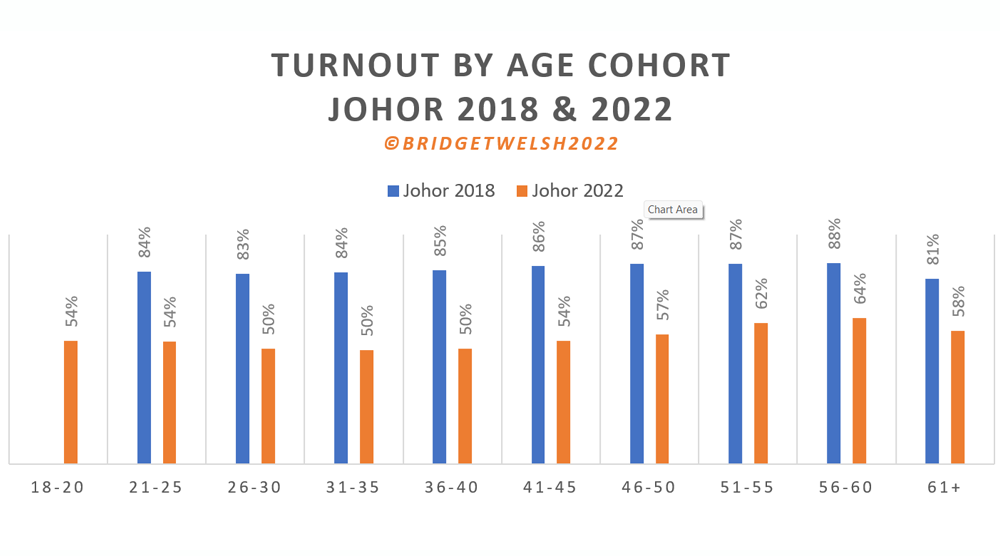

Let’s turn to the Johor analysis, starting with turnout. The data shows that turnout dropped across age cohorts compared to GE14, averaging around a one-third drop for most cohorts. As such, turnout decline should be seen as a broader phenomenon, not tied to just one group/cohort.

There was some variation in turnout levels by age. The majority of Undi18 voters voted. More than half (54 percent) of Undi18 voted, similar to those between 20-25.

As data showed in Malacca, the youngest voters are as politically engaged as the rest of Malaysians, if not more so. The outreach to this community in initiatives such as Undi18 did have an impact, increasing participation, but clearly, more voter education and outreach to younger voters are needed.

Outreach should extend beyond Undi18. The most voter disengagement begins after 25. It is between 26 and 40 years old, where there was the most drop in turnout. Many of these younger, but not youngest, Johor voters were outstation.

Yet, this pattern was evident in Malacca as well, suggesting this drop in turnout is more than just the distance of voters to the polling booth.

Dissatisfaction with political parties is also evident. Younger voters between 25-40 years, those socialised in an era of weaker political parties, are more disengaged than similar voters in these age cohorts were in earlier elections.

While many are fatigued and others disappointed in the transformation of national politics, many are not as connected to electoral politics compared to the past.

As ages rise above 40, there was more participation in the state election, with those in their 60s turning out to vote the most. Those over 60, who comprise over a fifth of Johor’s electorate, were less inclined to vote compared to those in their 60s.

Here the concern with the Covid-19 effect is evident. Yet, elderly voters had the lowest drop in turnout compared to GE14, only 23 percent, highlighting the persistent importance of this core ‘older’ group in shaping electoral outcomes in states like Johor.

Divided Undi18

How then did different age cohorts vote? Who did they vote for? Let’s look at Undi18.

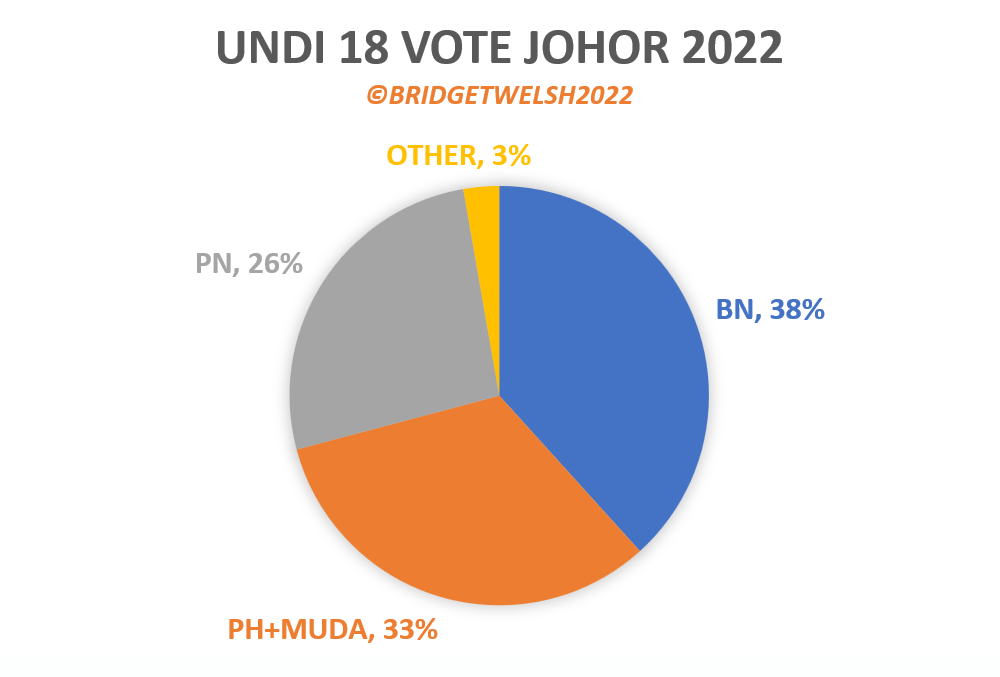

The findings suggest that Umno/BN captured the lion’s share of the new voters, an estimated 38 percent. This was followed close behind by Harapan+Muda at an estimated 33 percent. PN captured over an estimated quarter of their votes, 26 percent – a significant increase from what PAS received in GE14.

This division among younger voters in who they voted for reflects the national trends of a divided electorate. It is particularly divided among voters under 45, the overwhelming majority of voters. As opposed to GE14, it is not a polarised electorate but one divided into three.

A key feature that has changed since GE14 and is clear in Johor is the misperception that Harapan captures the most youth support. Despite bringing in the vote for 18 to 20-year-olds in Parliament, Harapan did not win beyond a third of their loyalties in Johor.

On its part, Umno/BN also did not return to the loyalty levels shown by the youth pre-2013, as it is only capturing a plurality rather than a majority of younger voters.

The Undi18 vote, and the rest of the youth vote, remains divided, to be captured and won given the pattern of the young changing their partisan loyalties.

Gaps and gains in the middle

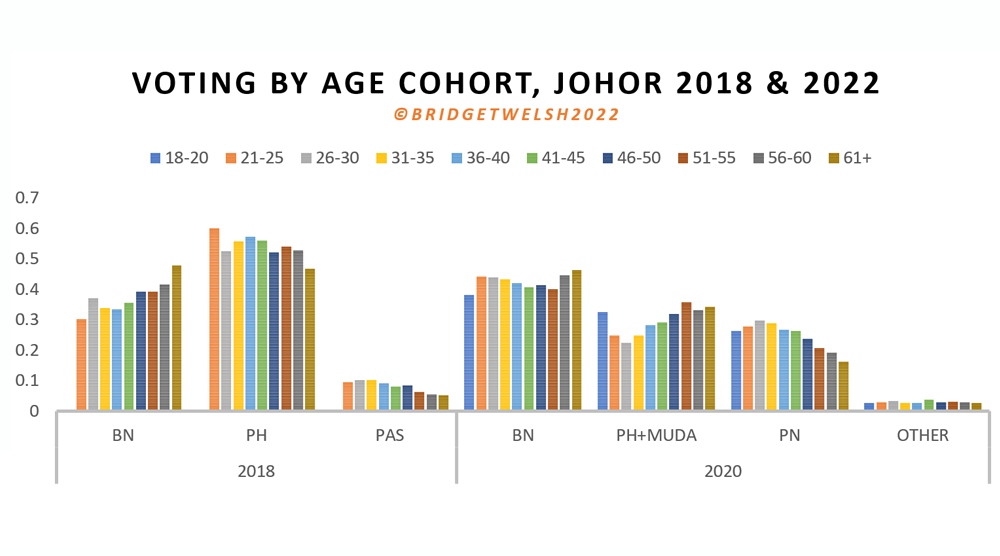

Harapan’s decline in youth support is another striking finding. Harapan’s youth decline in Johor is concentrated among those 25-40 years old, the same group that is not turning out to vote.

The largest decline is among 25 to 30-year-old voters, a whopping drop of an estimated 35 percent in support.

First-time voters in GE14 left Harapan in droves less than three years later, with this extending to those through their 30s, an estimated average 30 percent drop. The level of youth support in Johor for Harapan is lower than that of the Malacca polls.

These 25 to 40-year-old voters are moving primarily to PN, which now has its core support in Johor (and Malacca) among younger voters.

Among voters 25 to 30-years-old, PN increased its vote share by an estimated 20 percent, with similar increases in voters up to 45 years old.

Not to be left out, BN also made gains among these 25 to 40-year-old voters in Johor, with the highest gain of an estimated 10 percent from those in their early thirties (31-35 years). The youth vote for BN remains fluid.

Muda’s modest youth boost

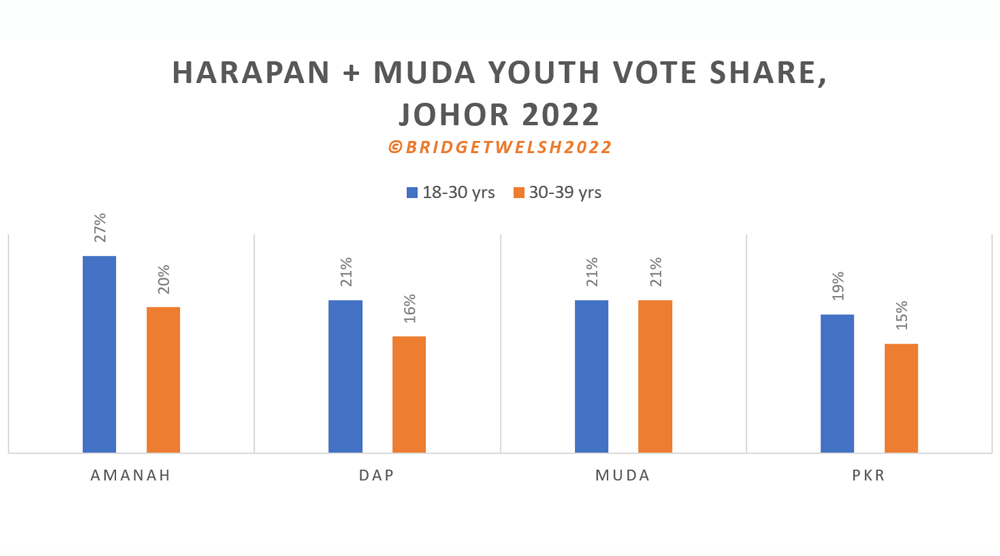

The findings also show younger voters are attracted to different actors within the opposition. Bersatu won more support than PAS in Johor, for example.

In Harapan’s Johor results, detailed below, Muda provided a boost for the coalition with the support of voters under 21, and also secured more votes than Harapan component parties from voters in their 30s.

Findings suggest Amanah won the most youth votes, followed by Muda, then DAP, and finally PKR.

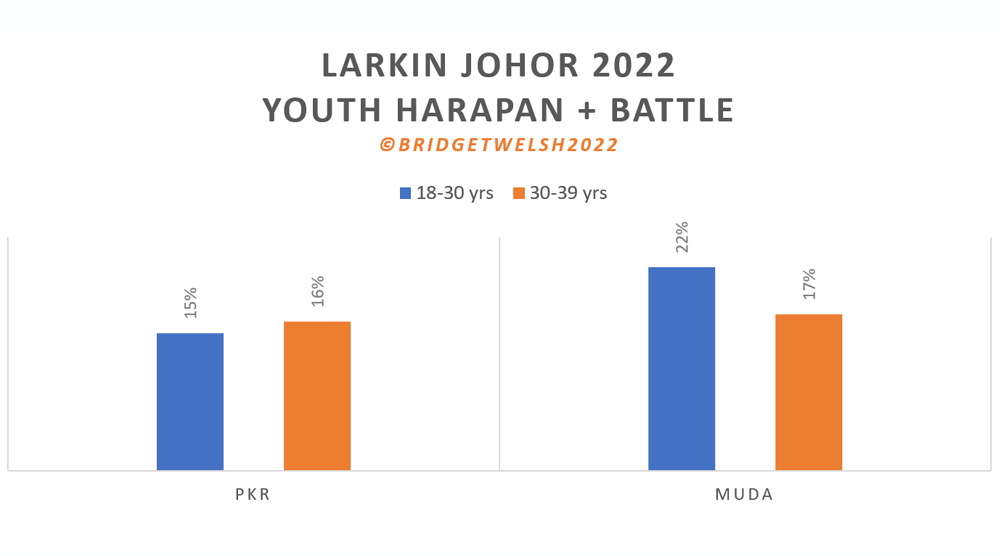

A look at the Larkin battleground seat, where PKR and Muda competed against each other is illustrative.

Both parties won support from younger voters, but Muda won more, especially among voters under 30 - an estimated 22 percent for Muda to an estimated 15 percent for PKR.

The youth are divided in their support even among the opposition options, suggesting not only their weaker party loyalties but a willingness to be selective, waiting for reasons and inspiration to vote.

Elder BN advantage

While the contest for the youth is intense among parties, there is more consistency among older voters; the Johor findings suggest that the elderly are less likely to change their support.

This advantaged Umno/BN, who won over 45 percent of those in their 60s and above. While not a majority of the elderly, without this high support of the elderly, Umno/BN would not have won the high number of seats it secured in the Johor outcome.

When looking at Umno/BN’s political base, its composition is concentrated among its long-time loyalists, who overall have remained faithful to the coalition, especially in Johor where Umno has strong roots.

In contrast, PN did not manage to win over older voters, less than 20 percent, although Harapan held on to a third of more senior voters. This lack of elderly support is a serious gap in both coalition’s electoral support, especially PN.

Looking ahead, parties across the political divides have their work cut out for them. No one coalition secured a majority of any of the different age cohorts.

Despite Umno/BN’s elderly advantage, there is no secure age cohort vote bank. Even Harapan’s support among voters socialised during the ‘reformasi’ generation, now in their late 50s, are changing their vote away from Harapan.

The fluidity and the division of the vote in Johor, especially the youth vote, shows that none of the parties should be over-confident of victory going into GE15. - Mkini

BRIDGET WELSH is a senior research associate at the Hu Fu Centre for East Asia Democratic Studies and a senior associate fellow of The Habibie Centre. She currently is an honorary research associate of the University of Nottingham, Malaysia's Asia Research Institute (Unari) based in Kuala Lumpur. She tweets at @dririshsea.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of MMKtT.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.