As the reality of multi-cornered fights set in, Johoreans are assessing the buffet of candidates on offer in the coming polls.

There is interest but considerable scepticism has set in. The common refrain is: “They are all the same”, coupled with a course of confusion on who is with which party and what they stand for.

A closer look at the 239 candidates from 10 different parties does reveal that there is variety among the candidates, from traditional local warlords and businesspersons to on-the-ground social activists and local councillors.

Parties are trying to respond to calls for better and more inclusive representation, but they are facing a more distrustful public, even among their traditional political supporters and especially among younger voters.

To be fair to those contesting, many of the candidates fielded are locally grounded and eager to serve (not just themselves). They are, however, really struggling to connect to voters.

Here are some observations about the candidate dynamics in Johor compared to recent state and previous elections:

Greater inclusion

First is the greater inclusion of women. While the number only reaches 37 or 15 percent of overall candidates, women have been slated in seats they can win and their presence has already brought greater attention to the issues ordinary Malaysians care about – education, health care and a stronger social safety net.

Johor has always had prominent strong women in politics and this election is no exception. Umno was born in the state, but it is Wanita and Puteri Umno (first led by Johorean Azalina Othman) that has the strongest grounded roots in the party.

Beyond the handful of female incumbents contesting, the female candidates to look out are Wanita Umno’s Harunizah Hassan, a civil engineer contesting in Pulai Sebatang, Johor MIC Wanita chief and businesswoman Saraswathy Nallathamby in Kemelah, local activists Amira Aisya Abd Aziz and Afiqah Zulkifli contesting for Muda in Puteri Wangsa and Bukit Kepong respectively, activist Napsiah Khamis Maharan from PKR in Kempas and Marina Ibrahim from DAP in Skudai. The election has the potential to bring more women, especially younger women, into the state assembly.

Much has been made about “new faces” and the inclusion of younger candidates. Johor’s election follows recent trends of slating younger candidates and decreasing the overall age of those contesting – a long-overdue need to give voices to younger people.

What differentiates these state polls is how parties are grappling with how to “represent” young people. With the entrance of the Undi18 and previously unregistered voters, there is now more serious thought being placed on how to change policies and bring about more inclusive governance.

Previously, the focus has been on distributing benefits for the young – job fairs, sports stadiums, laptops. This time around, there is more attention to increasing wages, strengthening training, and enhancing digital connectivity for entrepreneurship and education.

Part of this is a recognition that the concerns of young people need to be treated more seriously, and their support cannot be taken for granted. These policy messages, however, have yet to reach most voters.

What is initially resonating for many young voters is that they matter, and this is causing a bit of excitement on the ground, especially compared to Malacca polls.

Different views of frogs

In contrast, the entrance of new parties and “frogs” contributes to confusion and reflects disappointment. Many of the new parties are fielding people who were attached to other parties and coalitions earlier.

Voters are having a hard time keeping up. Repeatedly they respond with the refrain that they do not know what the different candidates (and parties) stand for.

Johor’s candidate slate is full of “frogs” both in a strict definition – someone elected who has changed parties and in a less strict sense, someone not elected who has changed partisan loyalties. Rengit’s Khairuddin A Rahim changed from Amanah to PKR, for example. He was among three Amanah representatives that moved to PKR.

Well-known former education minister Maszlee Malik contesting in Layang-Layang switched from Bersatu to being an independent then to PKR.

This January before dissolution two Bersatu representatives left the party to join Umno – Mazlan Bujang and Mohd Izhar Ahmad. Neither is contesting again, but these defections add to the distrust and concerns about sustainable representation in which almost all of the parties have been affected.

Frogging is seen through partisan and coalition loyalties with it being accepted by some if the frog has jumped to the “right” side – depending on the side a person is from.

Some are trying to move beyond the “frog” label. Puteri Wangsa candidate Steven Choong is campaigning on his record of service and accessibility.

His candidacy will serve as a test to assess whether the anger over the Sheraton Move and its aftermath remains salient or whether voters are concerned with access and service in a time of economic hardship and uncertainty.

Johor's election brings to the fore one of the difficulties in assessing how to interpret the “frog” label when blanketly applied, and the impact of fluidity in changing coalition politics and the emergence of new parties.

A good share of Warisan’s and Pejuang’s candidates were associated with other parties before, as is common with new parties.

Even candidates who changed loyalties before the election are facing greater scrutiny and unrealistic litmus tests of “loyalty”. Candidates are being questioned for adjusting to the new more fluid context, accused (sometimes unfairly) of being opportunistic rather than principled.

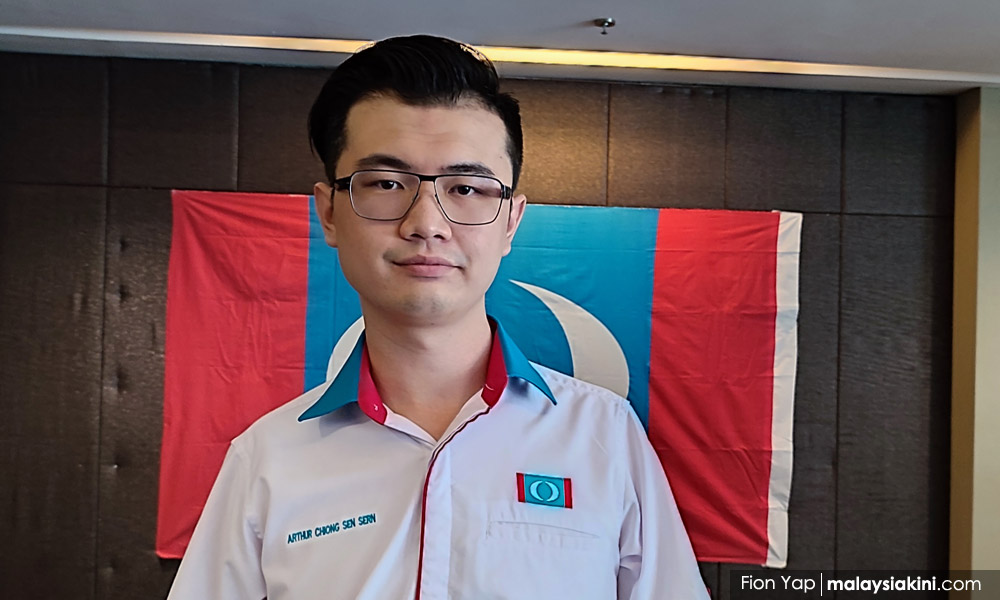

PKR’s Bukit Batu candidate Chong Sen Sern, for example, was believed to be supportive of MCA at one time, although has been aligned to PKR in recent times, and this charge is being used locally against him. Frog labels are taking on different meanings.

Rise of candidate factor

Most voters are still trying to figure out who is who and what they stand for. Many of the parties are clearly not ready for polls, with candidates arriving at some places overnight.

While more of the candidates are from or have ties to the respective local communities, quite a few do not actually live and work in the seats they are trying to win.

There is a battle over who is more “local”. Some parties are banking on the ties to local government to enhance their appeal; MCA, for example, is slating many municipal councillors such as Lim Soon Hai in Skudai, hoping that access to local government will work to their advantage.

Others are labelling candidates living outside of the actual constituency, but with ties to the area, as “semi-parachutes”.

There is an expectation at the dun level that the candidate has been present and is known in the community. Now, during Covid-19, more expect candidates to be actually living in the community.

In the Johor campaigns overall, the “candidate factor” is being stressed to a greater degree – accessibility, experience, hard-working, personality and in some cases even more locally-focused platforms. Even in campaign strategies, the focus is on winning support for the person rather than the party.

A good example of this is the contest in Rengit, where PKR’s Khairuddin, the former representative of neighbouring Senggarang, is contesting against Umno veteran Mohd Puad Zarkashi focusing on his record of service and accessibility.

From campaigns to character, the candidate factor is emerging now more important in Johor compared to GE14. Ironically, in some ways, Johor is echoing Sabah’s polls, ironic given the entry of Sabah-based party Warisan.

As in Sabah, access to greater resources also will advantage certain candidates, especially in the last week of the campaign. The economic and social impact of Covid is ever-present. The pandemic underscores calls for assistance and access to local representation.

Part of this trend to the candidate factor is also the result of a lack of clear overall messages/platforms of parties and coherence of political coalitions.

In a context of weak parties and even weaker clarity in campaign messages, every candidate effectively has to field for and promote themselves.

Importantly, even with greater distrust of politicians and confusion about them, voters remain hungry for better representation and they are looking with more scrutiny at their local candidates to get it. - Mkini

BRIDGET WELSH is a senior research associate at the Hu Fu Centre for East Asia Democratic Studies and a senior associate fellow of The Habibie Centre. She currently is an honorary research associate of the University of Nottingham, Malaysia's Asia Research Institute (Unari) based in Kuala Lumpur. She tweets at @dririshsea.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of MMKtT.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.