HISTORY: TOLD AS IT IS | Sept 7, 1981, was perhaps one of the most significant dates in Malaysian history after Aug 31, 1957.

On that day, the Malaysian government led by Dr Mahathir Mohamad, who had only been in office for two months, executed a coup to remove some of the final vestiges of British colonialism off the face of the country.

This was when the government, through Permodalan Nasional Berhad (PNB), surprised everyone by purchasing 50.41 percent of the share capital of Guthrie Corporation Limited, one of Malaysia’s largest British rubber and oil palm conglomerates, on the London Stock Exchange. The entire operation was completed in a matter of a few early morning hours, and was hence known as the ‘dawn raid’.

The raid was undeniably a political success on a never-before-seen scale. The Malaysian government's acquisition of a “colonial” corporation – the origins and establishment of which were part of the colonial economic policy of depleting economic potentials – has also been hailed as a triumphant event.

After centuries of colonisation, independent Malaysia (then, Malaya) was constrained to settle for the colonial economy, which was mostly a commodity-producing one. Plantation and mining companies owned and operated by companies registered on the London Stock Exchange from the British era remained key economic movers.

Launched in 1970, the New Economic Policy provided the first nationalised context for re-examining the roles of foreign-owned plantation and mining companies after years of a Western-friendly attitude. Restructuring ownership of corporate shareholdings was a major policy objective. For this, the Malaysian government established the PNB in 1979 under Mahathir, then deputy prime minister.

Plans were established to purchase reserved shares of approved companies in the private sector, as well as shares held in trust by other government agencies. PNB had even invested extensively in Guthrie, though it was thought that the latter was still characteristically colonial.

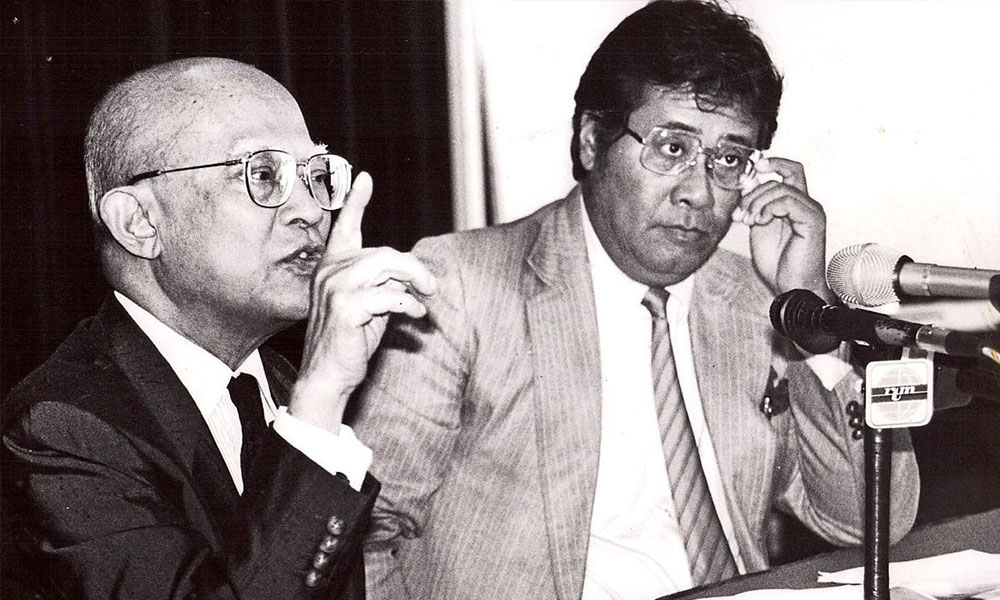

The former, for example, was not consulted on many of Guthrie’s investment decisions. Sensing this, Mahathir, right from his days as the minister of trade and industry, and several key personalities (including Ismail Mohamed Ali, the first Malaysian governor of Bank Negara Malaysia and then PNB chairperson, and Tengku Razaleigh Hamzah, then finance minister) hatched a plan of buying Guthrie.

A few months after Mahathir became the country’s fourth prime minister, the plan was executed. It was mainly led by Ismail and Abdul Khalid Ibrahim, then PNB chief investment officer. When the raid was over, PNB had taken over Guthrie Corporation’s assets, which were largely in the plantation industries of rubber, oil palm, and cocoa.

PNB also purchased 58 percent of the ownership in Harrisons & Crosfield, which was actually valued higher than Guthrie on the London Stock Exchange in 1982. It eventually held 82,000 hectares of plantation rubber, oil palm, cocoa, and coconuts and employed 18,000 employees.

Huge feat

It was a huge feat, particularly for a newly decolonised, industrialising nation, to have manoeuvred so strategically and stealthily to reclaim its economic stakes from the ‘neo-colonialists’. But, behind the pride, there was another reality of the affected employees, namely the wage-earning plantation labourers, the majority of whom were Indians.

In the post-independence period, the plantation community was already one of the most economically and politically disadvantaged. In the 1950s and 1960s, there was the problem of plantation fragmentation, which resulted in the layoff of thousands of Indian labourers. Those who decided to remain in the estates had to accept reduced wages.

Another issue exacerbated their situation in 1969 when the government’s work permit policy required non-Malaysian citizens to seek work permits for employment that could only be given to jobless Malaysians. Many Indian labourers had not applied for citizenship owing to apathy or ignorance, despite the fact that many of them were born in Malaya.

As a consequence, approximately 60,000 of them were forced to leave Malaysia, while more than 50,000 chose to remain in the estates. Those who stayed were filled with dread and uncertainty, afraid they might be deported if their contracts were not renewed.

In 1970, 46.5 percent of Indian labourers worked on estates, with the remaining 24.8 percent working in non-skilled employment. When compared to other ethnic groups, Indians had a comparatively high rate of unemployment. Between 1970 and 1975, the number of estate workers fell from 148,000 to 127,000, while poverty grew from 40 percent to 47 percent.

After the May 13 riots, Indian labourers were the economically weakest community, accounting for barely eight percent of the Malaysian population. In short, even well into the 1980s, the economic well-being of these labourers remained unchanged.

In the midst of these, the raid was a giant pail of salt poured into their economic wounds. The Indians had hoped for security in the form of better wages and working conditions with PNB’s takeover of foreign-owned plantations. Estate workers hoped that with a change in ownership and management, the new officials, who were all Malaysians, would be more compassionate.

However, the new management was solely concerned with increasing profits and keeping wages low. They also began hiring workers from Indonesia, Thailand, and the Philippines. Since the plantation owners complained about labour shortages, the government became more lenient in permitting large numbers of Indonesian workers to enter the country. By 1980, they accounted for some 20,000 to 30,000 out of the total 167,000 estate workers.

For the record, the estate workers were treated way too authoritatively. There have been reports of Malaysian managers penalising workers who exhibited a strong sense of independent spirit. The workers were not permitted to draw media attention to their work conditions.

A rubber tapper from an estate in Sungai Petani gave an interview to a Tamil daily (Tamil Nesan), which was published alongside his photograph. As a consequence, management suspended the employee for three days. When his son applied for a job after the rubber tapper retired, the estate’s contractors were told not to hire him since it would serve as a lesson to others.

Another incident occurred in an oil palm estate in Kluang, Johor, when a worker argued with the manager about water shortages faced by estate workers. The worker was fired with 24 hours’ notice.

Estate workers displaced

The estate management also sold plots to developers, profiting millions of dollars by displacing workers. During the construction of Putrajaya, Malaysia’s proud administrative hub, estate workers were served with redundancy notices with no prospect of compensation or relocation. The workers were dissatisfied, and as a result, they were labelled as troublemakers.

Finally, they were promised low-cost housing, a temple, and a Tamil school in the vicinity of Dengkil. In reality, they were only allocated 400 flats on three to four acres (1.2 to 1.6 hectares) of land.

Rubber tappers residing on Guthrie Property plantation lands (formerly owned by Highlands and Lowlands) were denied basic socioeconomic needs in the early 1990s after the properties were purchased by PNB in the 1980s.

Some 150 families who had worked for the plantation enterprise for several generations as rubber tappers and oil palm harvesters were affected by the conversion of the lands for property development. They were told to vacate their quarters on the two plantations because of government land acquisitions.

Attempts were made in 1997 to alter the laws in order to prohibit management from retrenching workers without paying compensation, but nothing came of it.

The dawn raid’s political and economic success came at the expense of the plantation workers. It took no account of the fact that Indian labourers had been working on their plantations for many years. The Malaysian management was, at times, adversarial, resembling or far worse than the colonial officials.

When estates were sold, the amount given to plantation employers in termination compensation was insignificant in comparison to the large profits made from the sale. Many were compelled to work more than two jobs to make ends meet, did not own their own homes, and lived in deplorable basic living circumstances. They suffered not just economically, but also socially since some of the younger generations were pulled into unlawful activities.

Despite its nationalistic pride, the ‘dawn raid’ was perhaps a socially irresponsible operation. -Mkini

SIVACHANDRALINGAM SUNDARA RAJA is an associate professor at the Universiti Malaya’s History Department. He is a well-known scholar in the field of Malaysian economic history, with numerous local and international research publications to his credit.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of MMKtT.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.