Prague is about 1,200 km west of Kyiv. If Vladimir Putin is pushed to nuke Ukraine's capital, radioactive dust from the fallout will likely poison all living things in Central Europe and beyond. Think Chernobyl.

Should I return to the safety of Sydney? No, unless my son and his young family are able to leave Prague with me.

Prague's proximity to Kyiv brings an unimaginable nuclear blast conceivably closer to home. The locals are constantly reminded of this possibility. At noon each first Wednesday of every month, air raid sirens wail for two minutes from strategically located loudspeakers.

That's part of Czechian public life – much of it spent commuting daily in the underground Metro. Sections of the mass transit network, built in 1974, also serve as bomb shelters.

There's a long history to Russian intervention in this Slavic landlocked nation – until December 1989 when hundreds of thousands mobilised against the Soviet Union at Wenceslas Square in what became known as the Velvet Revolution.

The peoples' protests ended 40 years of one-party Communist rule. Hence was born the democratic Czech Republic or "Czechia", as it's named in the UN list of member nations.

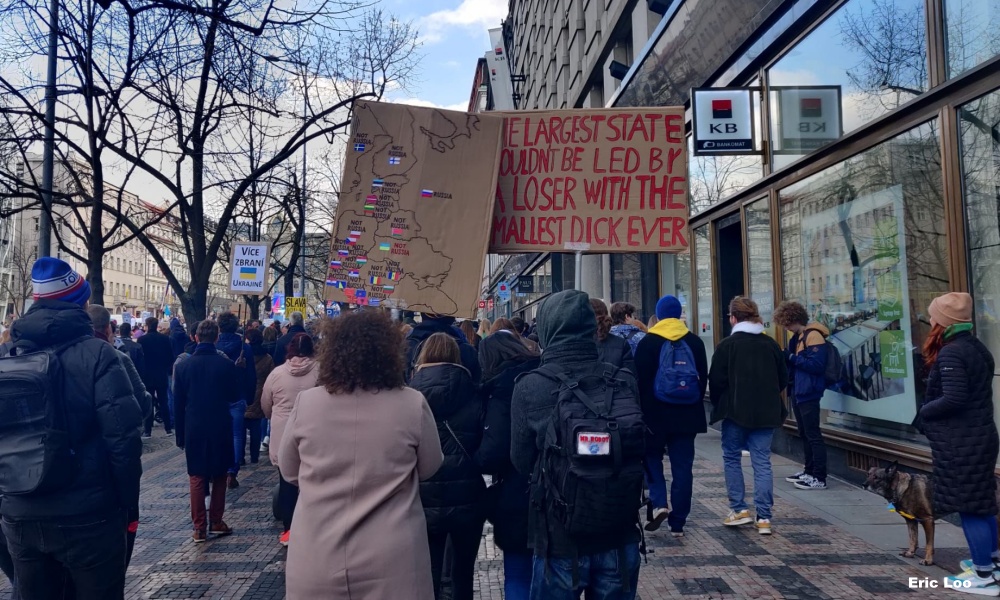

On the afternoon of Feb 27, I was among the mass of anti-war protesters at Wenceslas – oblivious to a possible Covid cluster. Many, non-masked, were draped in yellow and blue Ukrainian flags. I didn't need to understand Czech to feel the seething hatred for Russia and mockery of a Hitlerised Putin.

Burnished in the public mind is this dark portrayal: Vladimir Putin is a cold-blooded dictator intent on killing to restore a Soviet imperium.

The Russian-Ukraine conflict could as well be framed as Putin's mission to reclaim Russian lost glory, depending on what you have read and viewed.

Russia's military campaigns are couched in claims and counter-claims as documented in Nato's report, although Putin had in the past expressed interest in joining Nato.

Here's one perspective why Russia feels betrayed by Nato's phased expansion eastward in spite of Putin's continual opposition. And, another from an ABC correspondent embedded with pro-Russian separatists in Donetsk, eastern Ukraine, who reportedly shot down Malaysia Airlines flight MH17 from Amsterdam to Kuala Lumpur on July 17, 2014.

Insidious form of cyberwarfare

Reading the commentaries from Pravda, Russia Today, and even Al Jazeera, US arrogance and hypocrisy is as clear as Putin's ego-driven murderous attacks on his weaker neighbours - as depicted by American media and their allies.

The current conflict has indirectly exposed latent racial streaks among leaders and media outlets in the West. This is evident in their compelling compassion for the Ukrainians but painfully absent for the hapless fleeing the Taliban when the US withdrew its last troops from Afghanistan in August 2021.

Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison had even announced that his government would fast-track visa applications from Ukrainians, even as refugees and asylum seekers – many from Afghanistan, Pakistan, Iraq, Syria and Sri Lanka - are left languishing in immigration detention centres managed by private contractors.

The "whiteness" of war victims seemingly evokes greater compassion from Western-oriented leaders. This harks back to former Liberal prime minister John Howard's infamous Pacific Solution to deter the arrival of (dark/brown-skinned) boat people or "queue jumpers" on Australian shores.

My article, however, is less about the history of wars, population displacement or covert racism among governments. It is about another insidious form of warfare in cyberspace – disinformation, "alternative truth", digital manipulation, deep fakes, and so on. This is where readers play their role.

Readers need to be ever vigilant against falling for, and sharing, fake footage and 'alternative truth' from pro-US and pro-Russia outlets with few fair ones in between. How we differentiate the "good" nations from the "axis of evil" is essentially influenced by what we choose to read, share and reshare. It's easy to take blindingly opinionated sides in times of crisis.

Like their readers, journalists are swayed by what they have witnessed, notwithstanding their professional creed. They work on presumptions and sieve for digestible sound bites. Their field experiences delimit their interpretations of ground realities. Journalists frame their stories based on their assessment of explanations from particular political sources.

Even as journalists are trained to report impartially, they can only report part of actualities. Selective choice and intuitive news decision is part of journalistic work. Which, in itself, delimits what journalists know what they ought to do but could not – not all the time. This is where readers come into the truth-seeking mission.

With today's virtual access to news from anywhere anytime - the onus falls on readers to go beyond their established media outlets to fill the credibility gaps by verifying with, for instance, Bellingcat and other fact-checking websites. (A caveat: fact-checkers are as vulnerable to mistakes as journalists are on the frontline).

Journalists are as inclined as their readers to see international conflicts as a battle between "good" (the 'West') and "evil" (the 'non-West'). As former US president George W Bush infamously quipped to justify his unilateral attacks on Iraq after 9/11: "You're either with us or against us." The victorious (re)write the history.

And, let us not forget the late General Colin Powell's speech to the UN about taking out Saddam Hussein and his weapons of mass destruction. We know now – and many independent bodies suspected then – that there were no WMDs. The unilateral strikes on Iraq and other terrorist-laden nations came with heavy human costs.

The relentless message from the Western hemisphere though is this: the US, with its democratic ideals, is the only "righteous" nation that can save the world from itself. That has been the message unchallenged since the UN established its permanent headquarters in New York City in 1956.

Ultimately, Western democracies are as accountable as the non-West for committing human rights abuses and shirking steps to redress social injustices. None are faultless. - Mkini

ERIC LOO is a former journalist and media educator in Australia and parts of Asia.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of MMKtT.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.