SPECIAL REPORT | When former air force technician Safwan Saleh started a side project of re-selling custom watches, he did not envision he would soon start his own clothing brand, Petak, in 2016.

The brand, featuring Safwan’s exclusive designs, started off only with an online presence, but soon he was generating enough business to open a brick and mortar store in Cyberjaya.

As the business grew, the entrepreneur had planned to open three more outlets by the end of 2020. And then Covid-19 hit, and expansion plans turned into a game of survival.

To keep his business afloat, the 34-year-old said he attempted to apply for a loan from Tekun Nasional, an agency created in 1998 under the Entrepreneur Development and Cooperatives Ministry for bumiputera businesses.

The facility offered a maximum of RM50,000 loan but “red tape” and offers to use a “cable” to guarantee a loan of RM20,000 soured the experience.

“This was in March this year... I was given a contact number by my company secretary who said, ‘just give it a shot’.

“There was too much bureaucracy. I did not follow up with the next steps because they told me I am only eligible to get RM20,000 (from RM50,000),” he said.

Safwan is one of many bumiputera entrepreneurs who, a generation after the New Economic Policy, are wondering if the help promised through affirmative action policies would reach them.

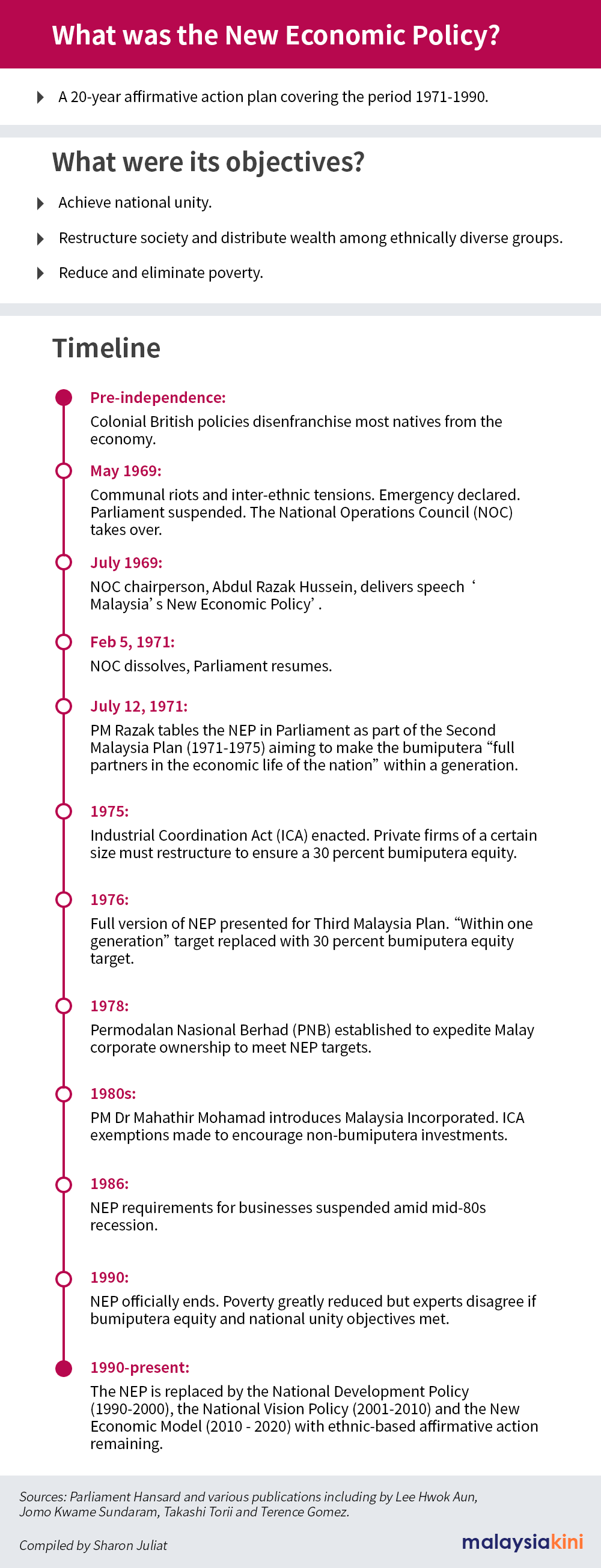

Tabled in Parliament 50 years ago as part of the Second Malaysia Plan on July 12, 1971, the NEP was promoted as a 20-year strategy to reduce overall poverty rates and restructure societal imbalances attributed as a trigger that sparked the 1969 race riots.

Although it formally ended in 1990, it laid the foundation for race-based affirmative action which continues in national policy to this day.

Reduction in poverty, a growing Malay middle class

Looking back 50 years, one of the measures many supporters of the NEP have used to show its success was the decline in national poverty rates, particularly among the bumiputera.

In 1970, about half of the national population lived in poverty. Among the three major ethnic groups, the bumiputera - made up of Malays and the indigenous population - were the most poor, with 65 percent of the segment living in poverty.

In 1990, at the end of the NEP, only 15 percent of the population were impoverished while just a fifth of the bumiputera lived in poverty.

The Malay middle class also expanded in the same period, making up 12.7 percent of the middle class in 1971, and 27 percent in 1990.

But for entrepreneurs like Safwan, today it feels like he is part of a “forgotten (bumiputera) middle class”, with wealth disparity within the bumiputera community seemingly expanding.

“We hear of the government announcing large amounts of funds (to assist bumiputera entrepreneurs) but when we try to apply, it is a different story,” he said.

While the NEP was first envisaged as a means to ensure that “within one generation”, to be “full partners in the economic life of the nation”, the target eventually set down on paper was that of corporate equity - something far from the sights of small bumiputera entrepreneurs.

When the full-fledged NEP was presented in the Third Malaysia Plan in 1976, the target set was for 30 percent bumiputera equity, alongside 40 percent in non-bumiputera hands and 30 percent foreign.

The 30 percent target was lofty, with bumiputera corporate equity at only two percent in 1970. Experts believe the target has not been achieved to date.

In fact, Ideas-Yusof Ishak Institute Malaysia Studies programme director Lee Hwok Aun said the figure peaked at 23.4 percent in 2011, but it reduced to only 16.2 percent in 2015 - and this includes equity held in the hands of individual bumiputera and trust agencies. (See chart below)

Bumiputera states are still poor

One researcher who has diligently studied the NEP and its predecessors, and its impact, is Universiti Malaya political economy professor Edmund Terence Gomez.

He said over the years, instead of bridging the gap, the NEP has created “spatial inequalities” with higher poverty recorded in Malay-bumiputera dominant states.

“If you look at the poorest states in this country, they are Kelantan, Terengganu, Kedah and Sabah. These are all bumiputera-dominated states.

“If the NEP is still around now, it would have been 50 years of NEP or NEP-like policies targeting the bumiputera. So why are the poorest states still bumiputera-dominated states?” Gomez questioned.

The economy is also very much concentrated within the central territories of Kuala Lumpur and Selangor, which contributed to 40 percent of the annual GDP in 2018, while bumiputera-majority states like Kedah, Kelantan, Pahang, Sabah and Sarawak were far behind, Department of Statistics data shows.

Gomez attributed the numbers to unequal access, where allocations intended for the poor were “hijacked” by others in more privileged positions, in what he terms “crony capitalism”.

“People who needed help didn’t get it and that’s why now we have this problem of disparity that we talked about,” he said.

The impact of corruption on the bumiputera agenda was raised in Putrajaya’s Shared Prosperity Vision 2030, a policy document that set out the national agenda just like the NEP.

In it, the government noted the disproportionate contribution of bumiputera small to medium enterprises (SMEs) when contrasted with the amount of contracts awarded to this group in 20 years up to 2015.

Government data recorded RM1.1 trillion procurement for development, supplies and services under the 7th Malaysia Plan to 10th Malaysia Plan, with over 50 percent allocated to bumiputera companies.

And yet, in 2015, bumiputera SMEs contributed less than nine percent of the annual GDP.

While crediting the success of affirmative action in education, Gomez said the same could not be said for bumiputera participation in business, citing only one or two prominent names among Malaysia’s Top 50 companies.

Unity still wanting, divide now also intra-ethnic

He said the NEP also seemed to have missed the mark on its other main goal - to foster national unity.

A perpetuation of race-based policies beyond the NEP has, however, led to ongoing debates on rights and identities, according to Gomez.

“There is a sense of marginalisation among some segments of society,” he said, adding that this has driven an estimated three million Malaysians to live overseas, many of whom are professionals.

“Some of those who have left, interestingly enough, are people with wealth, education and they moved abroad,” he said.

He said the feeling of marginalisation is not just inter-ethnic between the bumiputera and non-bumiputera, but also within the bumiputera community.

“Among the bumiputera, it is because they lack access to rights meant for them but were hijacked. Class disparities have then emerged within the bumiputera community,” he said.

This then also led to distrust and strained inter-ethnic ties, he said.

The abuse of NEP, he said, has contributed to the decline of public institutions including schools, universities and government agencies, leaving the poor - unable to afford private alternatives - with a lesser choice.

Rebuilding inter-ethnic trust by moving to a needs-based policy

Fifty years after the NEP was introduced, there is still very much a lack of an “evidence-based” approach in measuring the impact of policy, including race-based affirmative action, UM’s International Institute of Public Policy & Management (Inpuma) executive director Shakila Parween Yacob said.

It has made it difficult to dismantle race-based policies, and foster trust among the different ethnic groups, she said.

She said decades of abuse of affirmative action within the bumiputera community had led to severe strain on inter-ethnic ties, especially when fuelled by political interests.

This seemed to diverge from the inclusive vision of Malaysia espoused by Malaysia’s founding fathers, which had led to the NEP’s initial success, she said.

“I believe we must not come up with blanket race-based policies anymore. It has to be evidence-based.

“If someone asks, ‘Why do we need to help the Malays?’ then we can say, ‘Here, these are the data. This is what is happening in Kuala Terengganu’. So that builds trust among ethnic groups,” Shakila said.

Since the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic, she noted how existing wealth gaps have grown larger, with lower-middle-class families suffering a loss of income and pushed into the lower B40 category.

“This reverses the success we see happening through the NEP, especially among Malay communities,” Shakila added.

Moving away from a race-based policy to a needs-based policy would also address the criticism that the NEP and its legacy had further marginalised non-bumiputera communities in need.

Having spent decades working with the marginalised communities of different ethnicities, Parti Sosialis Malaysia deputy chairperson S Arutchelvan believes Malaysia needs to shift to needs-based affirmative action regardless of ethnicity.

He said the introduction of the NEP in 1971 to restructure the unequal society left by the British colonial government was the correct system at the time.

In fact, Arutchelvan argued, the controversial education quota system which many non-bumiputera feel unfairly penalises them and made it harder for them to enter university, had helped many underprivileged Indian students, too.

“If it was strictly merit-based, most of the top seats would go to the Chinese ethnic group (who were more economically privileged at the time), and most Malays and Indians would have suffered,” he said.

Now, decades after Independence, he said, moving away from ethnic-based policies would ensure everyone who needs help has a higher chance of getting the assistance needed.

“This would ensure assistance for a majority of Malay-bumiputera while the Indians, Chinese and other ethnic groups will get a fair share of the cake without feeling alienated,” Arutchelvan said.

But doing so will require major political will, which may be in short supply in a society where identity politics remain centre stage, and ethnic-based political parties the main actors.

Quotas still important, but the objectives must be clear

One objective of the NEP was to eliminate the identification of sectors and industry with a particular ethnicity. In other words, Malays are not just destined to be fishermen and farmers, they could be anyone they want to be.

It was to this end that racial quotas were set in various sectors including education and business.

How might similar quotas be used today to eliminate similar identifications of certain ethnicities with certain occupations, or to ensure diverse representation in other sectors?

Economist Muhammed Abdul Khalid believes it would be “hypocritical” to object against racial quotas to advance bumiputera participation in certain areas - like a quota for bumiputera women in the workforce.

Conversely, the same argument can be put forth for quotas to ensure non-bumiputera participation in other areas, like the civil service which is now dominated by the bumiputera, Muhammed was quoted as saying by local magazine Svara.

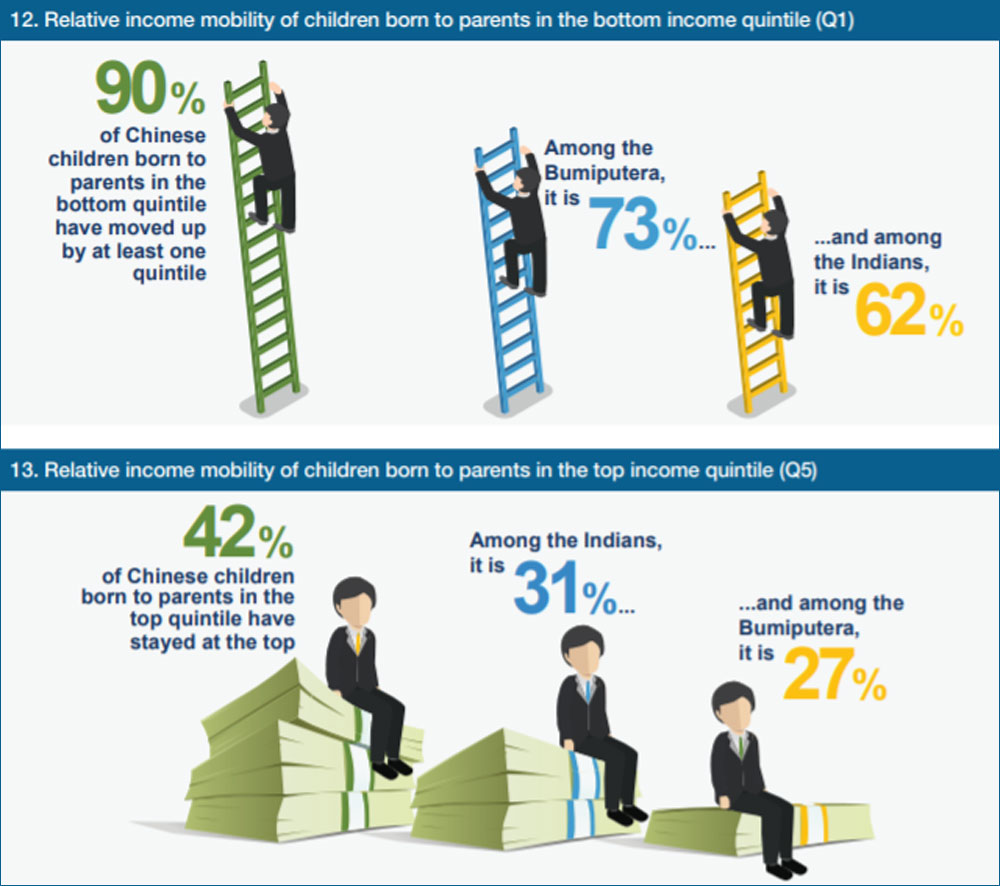

In 2016, while at think tank Khazanah Research Institute, he co-authored a study on socio-economic mobility and found that 73 percent of bumiputera respondents born to parents in the bottom household income quintile, said they were better off than their parents.

This may indicate that pro-bumiputera affirmative action has contributed in some way to assist the worst off in the community, and it was not entirely captured by the elite class.

However, the same study found that a lower proportion of Indians in the same category reported to be better off than their parents.

Muhammed said among improvements that could be made to ensure equitable outcomes for all is to make scholarships available to underprivileged Malaysians regardless of race and to bar bumiputera-only scholarships for the wealthier among them.

He also proposes stricter measures to ensure government contracts are not awarded to “Ali Baba” companies owned by a rentier class of bumiputera, whose contribution was just to lend their name to a non-bumiputera company to bid for jobs.

Within Putrajaya’s Shared Prosperity Vision 2030 is a 10-year roadmap with a familiar goal - to restructure the economy and ensure equitable distribution of wealth.

It also targets that bumiputera SMEs, like Safwan’s company, will contribute to 20 percent of the annual GDP by 2030. Like the equity targets set by the NEP in the early 1970s, this is an ambitious target, from just nine percent in 2015.

For bumiputera entrepreneurs like Safwan and small businesses like Petak, however, 2030 may be too far ahead to see.

His goal today is the same as other SMEs, bumiputera or otherwise: he just hopes to survive the pandemic in one piece. - Mkini

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.