“We have wasted our time for 60 years trying to find our way, not just for the nation but how far we progressed in our goals.”

– Tawfik Ismail

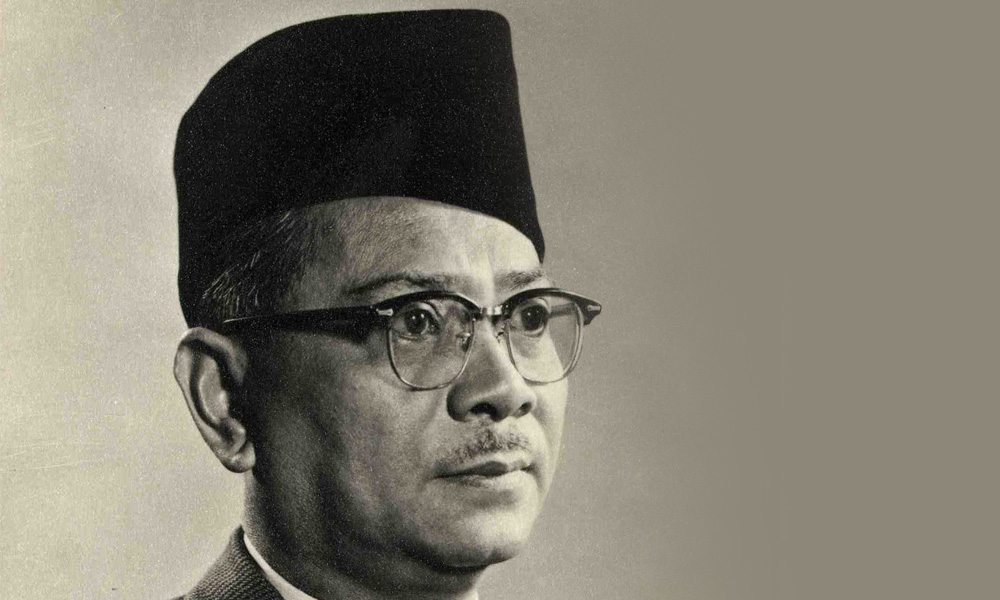

In this extensive interview, Tawfik Ismail, the eldest son of the late Dr Ismail Abdul Rahman, shines a light on his father’s legacy.

Ismail (above) is always characterised as a “reluctant” politician which basically means, the clash between one’s ideals and the realpolitik of the job. The political turmoil we are witness to today, are the chickens coming home to roost, of political plays back in the day.

Tawfik is cut from the same cloth as Ismail and the big question is, will history repeat itself, for a son, whose personal and political views mirror that of his father?

As someone who has left and returned to the political arena, what kind of politician do you think your father Ismail was and could his "moderate" approach survive in Umno today?

It was his memory and observation of politics in Australia as a student after the restrictive colonial restrictions he experienced in Johor Bahru, and the local Malay palace politics that was a feature of his family’s service in Johor that moulded his approach to government.

Those early impressions, and the exposure he was given by Gerald Templer (the British supremo in Malaya), he wrote in his letter to Tunku Abdul Rahman that the “most crucial and formative period for Malayan politics (was) the period from 1954 to 1955” in which he helped craft some important policies which included Land Development Ordinance of 1956 which gave birth to Felda, gave him an invaluable advantage in working with the bureaucracy because post-independence, those who worked with him became the implementors of the new government’s policies.

Because of Abdul Razak Hussein’s illness and the anticipation that my father would have taken over, it may be correct to assume that the Razak-Ismail policy direction from 1970 till his death in 1973 was tailored for an Ismail succession.

If he had succeeded Razak, it would be my speculation that a succession plan would have been effected, and that would have concentrated the minds and energies of those chosen to lead to compete for the laurels of leadership, and they would have needed to impress a prime minister of intelligence, experience and integrity whose goal would have been the achievement of the New Economic Policy (NEP) within the 30 years that he had set for the nation.

The NEP would have been implemented differently than it has been and most certainly certain political personalities we are now used to seeing would not have been in charge. The Malaysia Agreement of 1963 would have been reviewed in 1973, by him as was planned, and perhaps Singapore might have been made a closer ally because of the respect Lee Kuan Yew had for him, and tycoons like Robert Kuok would not have divested, instead, they might have increased their investments and brought in foreign investment in greater numbers.

He might have capitalised on his extensive Western contacts in Europe and the United States built on his diplomatic experiences. As he wrote to Tunku, he spent a lot of his time explaining to the US government and business the conditions in Malaya and impressed upon them the need to bring capital in for investment to counter communism.

He influenced a fair number of industries to locate in Malaya over the years since his ambassadorship. Incidentally, A&W established its outlet in Kuala Lumpur in the 60s due to his encouragement.

He was chairperson of Guthrie, Nestle and Malayan Banking during his retirement from politics in 1967 till his recall in 1969 and multinationals would have been confident enough to see a prime minister with business experience in charge to encourage their home office to invest more.

He and Razak were close to Lim Chong Eu in Penang and would have made Penang a rival to Singapore as a destination for investors.

He might have been able to govern the country with less of the Arabism that was a feature of the Dr Mahathir Mohamad-Anwar Ibrahim years. Unlike most of his contemporaries, his exposure to Middle East politics during his service as a permanent representative to the United Nations would have tempered any adoption of Arab thinking that might have permeated the government machinery.

That and the succession plan he and Razak had planned would have made the government more secular and focussed on material progress.

Given the strong Islamic flavour of Malay politics now it would be speculative to imagine how he would govern Malaysia.

Why has the Malay political establishment since the beginning been wary and at times even hostile, to the political views of Ismail?

I am not aware there was any hostility.

I thought they applauded him when he said the MCA was neither dead nor alive. I think the Malay phrase he used was, Hidup Malu, Mati Tak Mahu.

Could you describe the attempts to diminish the legacy of Ismail, which some would argue began with the controversial manner in which your father was laid to rest?

When he passed away, it was very sudden and a shock to everyone, and there was speculation he didn’t die a natural death but was poisoned. Perhaps the Royal Malaysia Police should reopen their files and investigate since in retrospect it might even be likely that Razak’s health secret was leaked and there would have been leaders who were ambitious enough to contemplate the most drastic action to move to the top.

After he passed away the government made plans to build a memorial but until now absolutely nothing has been done.

A Malayan Banking director had once told me there was to be a scholarship to honour his name as a chairperson of the bank but till now nothing has been done.

There used to be a Tun Dr Ismail Atomic Research Centre (Puspati) and that has disappeared. The government refuses to amend the name of Jalan Tun Ismail to Jalan Tun Dr Ismail so people are confused as to whether it is named after my father or Mahathir’s brother in law.

The Umno building, which my father had responsibility for funding its development, and the house he lived in, is on that road. On the occasion of his 100th birthday in 2015, I wrote to Najib about these matters and regrettably nothing was done. I even wrote to Pandikar Amin Mulia as a speaker requesting a special doa in Parliament to remember him, but my request was ignored.

As a former member of Umno, I would argue a legacy member, has your father’s role in Umno been a benefit or a disadvantage?

I had a track record of setting up the nation’s first mini money market in Penang in 1979/1980 and for delivering on time, in fact, six months ahead of schedule, and below budget Mahathir’s first privatisation project TV3 in 1984.

So I was a known commodity to the Umno Leadership. In Johor, there was some resistance to my membership in Johor Bahru where I was born in September 1951, but I prevailed and won the election at the branch level for youth and the main committee and a few years later to the youth and division committees and a seat as a delegate to the general assembly.

Naturally, I was seen as a threat to the incumbents but as I stood only for committees I was not a serious threat until I became a member of Parliament in the new constituency of Sungei Benut and stood for vice head of the division.

Of your father, Kuok said this: “In my opinion, he was probably the most non-racial, non-racist Malay I have met in my life. And I have met a very wide range of Malays from all parts of Malaysia. Doc was a stickler for total fair play, for correctness; total anathema to him to be anything else. Every Malay colleague feared him because of this, including Mahathir”. Could you give an example of how your father embodied this particular quote?

He once told me a doctor must never lie to his patient. Whatever he did his intention was to cure and treat the symptoms and prescribe a treatment no matter how harsh if the result was recovery.

He did this to great effect in the first few days of the May 13 riots when he went hard and fast on the rioters, and did it with tact by sending in the Sarawak rangers to black areas affected by the riots so that race would not be a factor in keeping the peace.

When he was tasked with the Home Affairs Ministry he had the security and safety of the nation in his hands and he did his best to exercise that responsibility without malice or allow personal feelings to cloud his judgement.

He chose the most remote and least developed constituency to represent in Parliament. Chong Ton Sin of Gerakbudaya will attest to the humane treatment he was accorded when detained by my father.

In fact, Chong was so impressed by the library he was forced to read that he decided to make books his career. When Chong first met me, he shook my hand and embraced me and thanked my father for his experience.

My father was always careful in investigations and cleared the late Harun Idris from any blame for the 1969 riots.

In managing the internal security of Singapore, he was always careful to go through the Special Branch reports carefully before committing his childhood friend James Puthucheary to detention.

Could you elaborate on Ismail’s role in the independence movement, something which has been overlooked because of his time in government?

My father’s involvement in the independence movement was influenced by his family’s involvement in Malay nationalism and by his own personal experience with Australians where he was treated as an equal and accepted as a friend even though he was not white.

It made an impression on him that his countrymen could be as good as they could be destined to be given the chance and opportunity, what Australians call “being given a fair go”.

This made him different in temperament from his colleagues who went to England and returned as brown Englishmen.

Ismail referenced the kind of “money politics” that was endemic in the system even in his book, about Malaysia’s first year in the UN? How did Ismail navigate through the Umno system while still retaining his beliefs that politics is building a country and not building a political career?

It was difficult before independence and after to find any person willing to stand for office. Who would want to spend months representing a constituency like Mersing in the 50s and 60s with no tarred roads and no highway?

And spend a whole day driving there from dawn till almost sunset, and campaigning for weeks during school holidays because that was when the Umno machinery of teachers and housewives were free to act?

Money wasn’t the consideration then, and people cried begging not to be nominated as delegates to the annual party convention in Kuala Lumpur.

If anything, it was the extended family system that threw up politicians and leaders from among a clan and my father’s clan fielded a number of representatives for Johor and the funds were all family derived.

Incidentally, his father in law defied the sultan’s decree and voted for Johor to go along with independence.

My father and grandfather, I am proud to say, are two of the signatories in the independence document.

Why was the perception that Ismail was “controlling” Razak pervasive in the Malay political establishment?

As leaders who were close to each other and bound by loyalty to Tunku, my father and Razak were of one mind when it came to nation-building and loyalty to Tunku was an important factor because only Tunku had the stature to maintain unity and inspire a nation.

If Razak was behind a plot to oust Tunku, my father would never have agreed to be his deputy, so deep was my father’s love for Tunku. Razak who always did Tunku’s bidding would have confided any frustrations he had to my father as he knew my father had Tunku’s ear.

In the days after the 1969 riots, my father’s strength of character and ability to implement hard decisions and credible personality made him a close confidant of Razak and especially after Razak was diagnosed with his terminal illness, my father’s counsel became more valued and with a view that my father would succeed him.

Razak’s policies were also my father’s, so to an observer, it seems like my father was the strong man, but I think the reality was two patriots who trusted and were strong partners agreed to work together, unlike prime ministers that distrust their deputies and suspect them of backstabbing.

Seasoned political operatives have described how Ismail was considered by the non-Malays as a stabilising force in the contentious days after May 13 riots? Why did Ismail believe in the primacy of Parliament when there were forces around him that were pushing for Malaysia to take a darker path?

You have to recall that models of governance were either totalitarianism ala USSR and China or guided democracies like Indonesia and Thailand or an anarchic, free for all democracy like the Philippines.

Malaysia is a hybrid unlike any other country with its territories spanning the South China Sea, its religious and cultural populace, and a small armed forces establishment. Parliamentary democracy is the best safety valve for that kind of diversity.

Imperfect though it may be, democracy is also more marketable to investors than a dictatorship, and it allows for management talent to be identified and groomed because when played properly, it is meant to bring out the best.

Ismail when referring to the ultras who were demanding the resignation of the Tunku said this: "These ultras believe in the wild and fantastic theory of absolute dominion by one race over the other communities, regardless of the constitution... Polarisation has taken place in Malaysian politics and the extreme racialists among the ruling party are making a desperate bid to topple the present leadership." Does not the history of the past decades demonstrate that Ismail’s outlier beliefs have no place in mainstream Malaysian politics?

Unfortunately, the change in values occurred when the succession plan didn’t go according to schedule when my father passed away, and when Umno’s membership character changed from village teacher dominant to small business dominant and money politics took root.

The demographics of the nation changed too, with more Malays becoming urbanised and vocal in redressing economic imbalances.

Religion became the lubricant with the Iranian Revolution successfully overthrowing old ideas out the window.

Ironically it was the secular and liberal attitude of the original Umno leadership that gave space to parties like PAS and DAP to propagate their message and religious personalities to take advantage of the system.

In order to harness the Islamic wave to suit political ends, the constitution, Rukun Negara, and culture were made insignificant by an uncaring and ill-disciplined political establishment. - Mkini

S THAYAPARAN is Commander (Rtd) of the Royal Malaysian Navy. Fīat jūstitia ruat cælum - "Let justice be done though the heavens fall."

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of MMKtT.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.