MP SPEAKS | On March 16, a movement control order was issued in response to the Covid-19 pandemic. This was followed by advisories and frequently asked questions (FAQ) factsheet issued by the National Security Council (NSC).

I wondered how this information is communicated to the people in my constituency, particularly vulnerable groups with limited or no access to the usual communication channels. This may include the elderly population, children, people with disability and Felda dwellers.

My concern intensified upon learning that some individuals in my Pengerang constituency have been affected by Covid-19. Furthermore, Pengerang being the location of the Rapid Petronas project, we lost lives due to an industrial fire and explosion in the same week. Not a good week for the rakyat of Pengerang.

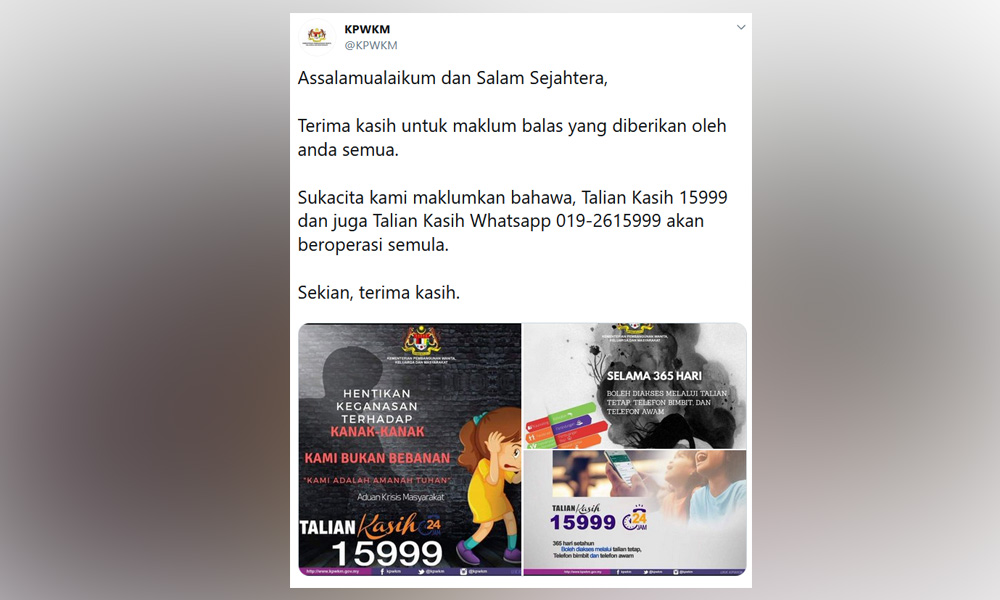

Imagine my distress when the Ministry of Women and Community Development (KPWKM) issued a statement that Talian Kasih would cease operation with immediate effect. Talian Kasih is a hotline and WhatsApp reporting platform which enables the public and victims to report cases of violence and abuse.

This decision was quickly overturned (within a few hours) as netizens, opposition leaders and myself came down hard on the ministry, highlighting an even more urgent need to protect vulnerable groups in times of crisis.

I highlighted that the movement control order specifically excluded the cessation of essential online services. As a firm advocate for vulnerable women and children, I believe this short-sighted decision could have been avoided if all stakeholders had a clear understanding of national guidelines and standard operating procedures for pandemic control and response.

It is not too late to ask ourselves some very difficult questions. To what extent is the government machinery liable for any failure, intentional or unintentional, including being negligent in carrying out its duties? How do we answer to legitimate expectations of the public?

Most Malaysians do not understand the complex relationship between ministers (political appointees) and public officers (duty-bearers for the implementation of government policies). Perhaps this expression, which I am used to hearing, sums it all - “Ministers come, ministers go... we stay”. Hence, while the public is always quick to judge and criticise ministers/politicians for the failures of policy implementation, little do they know or realise that ministers rely on the full support of the public officer machinery to deliver what is promised to the public.

As a member of Parliament and a legal practitioner, I am duty-bound to explain a sensitive legal issue to the public (and perhaps gently remind present ministers in office).

“Tort of misfeasance" is a legal terminology which applies to people in public office, not only to government servants but also for members of the administration, which include ministers as per article 160 of the Federal Constitution. It is a tort remedy for harm caused by acts or omissions that amount to:

- Abuse of public power or authority by a public officer who either a) knew that he or she was abusing their public power or authority, or b) was recklessly indifferent as to the limits to or restrains upon their public power or authority;

- And who acted or omitted to act a) with either the intention of harming the claimant (targeted malice); or b) with the knowledge of the probability of harming the claimant, or c) with the conscious and reckless indifference to the probability of harming the claimant.

In short, misfeasance is “intentional tort”, and the common denominator for “intent” is bad faith (source: Misfeasance in Public Office by Mark Aronson).

KPWKM's sudden announcement on March 18 reminded me of a Netflix crime documentary titled The Trials of Gabriel Fernandez. The documentary highlighted the failure of a government and social system in protecting the rights of a child. When children are denied access to a safe platform for reporting abuse and legal protection, we fail as a nation.

Case in point, the documentary established the failure of a government to effectively respond to a case of child abuse which eventually resulted in the loss of life. Despite multiple reports made by different parties to social services and the police, the system chose to believe the perpetrators and failed to take action. In the end, the perpetrators were charged while duty bearers escaped the consequences of their liability for failing to protect the child.

The documentary resonated deeply in my advocacy and support for the rights of children. As a lawmaker, I am constantly reminded that in ensuring protection for our children, accountability is required at all levels. We are all duty bearers and custodians of children –politicians, family, community, civil servants, law enforcement, legal practitioners, teachers et cetera.

In this time of crisis, let us not forget the vulnerable groups in our society. Let’s not make irrational decisions without looking for alternative solutions. And let’s extend our call for support to civil society groups when our hands are full.

AZALINA OTHMAN SAID is Pengerang MP and former law minister. - Mkini

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.