Malaysian cities have developed in a way that prioritises private transportation against mass transportation, and it’s costing homebuyers.

This is because strata residential property developers are thus compelled by regulators to provide up to two car parks per unit, driving up the cost of homes.

Developers, however, argue this is an unwarranted cost, as car parks are not all occupied.

Concurring, architect Lilian Tay said in some developments, the cost of building the car parking lots actually equal the cost of building residential units.

What this practically means is that homebuyers are paying as much for a spot to park their cars, as they do for a home for their families to live in.

“We are building car parks and not a place to live,” she said, at a conference organised by the Real Estate Housing Development Association (Rehda), in Bandar Sunway, on Thursday.

She said typically in Kuala Lumpur, about a third of construction costs go to building car parks, with basement car parks costlier than elevated car parks.

For first-time buyers who are barely able to afford to get on the property ladder, the additional cost of a car park could rule out a purchase, she said, even if the buyer does not need that extra lot.

“If you’re just affording to buy or cannot buy, (the difference in price because of an additional car park) is quite compelling,” she said.

“A car park will take 50 to 500 square feet, so you end up with a scenario where we’re building that much footprint for your car, as opposed to for your family.

“Reduction of car parks is the key opportunity to reduce housing prices,” said Tay, who is attached to award-winning firm, Veritas Design.

Compliance costs

Regulations requiring developers to provide up to two car parks per unit plus visitor parking bays were cited as compliance costs that drive up home prices, in Rehda Institute’s report launched yesterday.

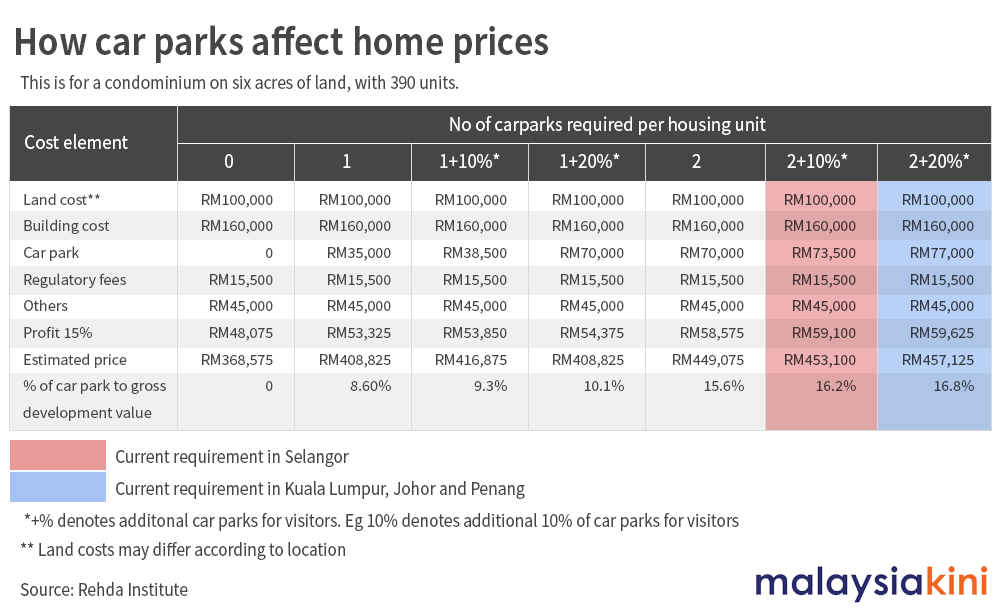

In its analysis, Rehda Institute found car park requirements can add up to RM77,000 to the price of an apartment in the below RM500,000 category. This makes up to 16.8 percent of gross development value, it said.

Developers in Selangor have to provide two car parks per unit plus 20 percent extra for visitors, while in Johor, Kuala Lumpur and Penang, an additional 10 percent extra must be provided for visitor parking.

However, requirements vary according to the type of development with requirements less stringent in lower-priced developments.

The Rehda Institute report, which analysed data volunteered by Rehda’s members, argues that in some developments, compliance costs add up to 50 percent of gross development value.

It argued that reduction in compliance cost could see a drop in home prices, at existing profit margins for developers.

It, however, did not address if developers would instead use those savings to boost their profits and not pass it down to homebuyers.

Instead of selling parking lots with residential units, Tay proposed car parking be rented on a needs basis, where only homeowners who require them will need to pay for the lots.

This also provides flexibility where parking lots can be rented for shorter durations.

“I may break my leg and need a car for a short period, so I can rent the parking lot for the duration,” she said.

She also proposed the number of car park bays be limited in inner-city housing, which is generally more connected to mass transportation, and for affordable housing to be integrated with public transportation.

Poor connectivity

Tay acknowledged that as it stands, many urban dwellers are forced to rely on cars due to poor connectivity between homes and public transportation hubs.

In Greater Kuala Lumpur, she said, development has been car-centric for the past 40 years, leaving fragmented neighbourhoods and poor walkability.

In most places, she said, it is a challenge to even walk 15 minutes due to obstacles like highways, structures or gated communities which block pedestrian access.

She said this directly impacts ridership on a mass rail, despite Kuala Lumpur boasting comparable lengths of metro rail to cities like Seoul or Singapore, where most people use public transport.

Tay, who is former Pertubuhan Arkitek Malaysia president, said transit-oriented development (TOD) as a concept was lacking even in the mass rail project.

TOD is an approach to development where urban spaces are designed to be integrated and accessible from each other and the rest of the city through easy walking and cycling connections with transit services.

“Having worked on MRT 1 and MRT 2, transport-oriented development is still a (new) concept.

“For MRT 1, it came too late. They have to run the lines and tunnels and approximate corridors and go because this portion (transit-oriented development) was not undertaken by the project delivery partner. It was a missed opportunity,” she said.

First and last mile

Meanwhile, Rehda Institute trustee Ng Seng Liong also urged the government to reconsider requirements to provide car parking lots in a strata development.

He said with rail lines stretching into the ends of Kuala Lumpur, reliance on mass transportation is only a viable option for many if local governments can ensure first and last-mile connectivity through feeder buses.

This could also ease traffic congestion which is reaching severe levels, he said.

“I am from Klang and this morning it took me one hour and 20 minutes to reach here (Bandar Sunway). If it was raining it could be up to three hours. This can be halved if people take public transportation,” he said.

Feeder bus systems already exist for MRT users and in some municipalities like Petaling Jaya, with varying success in boosting ridership in mass rail.

In 2018, the Pakatan Harapan government mulled making minimum parking requirements optional for developments closer to transit, to reduce house prices.

“As a proposal, if the requirement is made optional, maybe house prices can be brought down while at the same time more people would be encouraged to take public transport,” then transport minister Anthony Loke said. - Mkini

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.