SPECIAL REPORT | Sarawak prides itself as a state that has kept away undocumented migrants, but in its own backyard, many of its natives are stateless.

This is especially the case for the Penans, who for generations have faced obstacles in obtaining citizenship, in part due to excessive bureaucracy.

The issue is complicated by their nomadic culture and compounded by rural poverty, limited Bahasa Malaysia literacy, and inability to afford the luxury of travel to National Registration Department (NRD) offices in town.

The Penans are the last nomadic indigenous people residing mostly in Baram, Belaga, and Ulu Limbang, located more than 200km from Bintulu via rural roads.

In 2010, the State Planning Unit estimated 77 percent of Penans have settled permanently, 20 percent were semi-nomadic, while three percent are nomads.

Those living in the heartlands of Sarawak do not possess birth certificates, any identification papers, or MyKads.

The Penan Affairs Department of the Sarawak Planning Unit says there were 21,367 Penan in 2019. But most of them do not have any form of identification papers to denote they are citizens, let alone enjoy the benefits of being classified as bumiputera.

This despite their culture and practices being commodified when promoting Sarawak and Malaysia as a travel destination.

Walking for hours to register

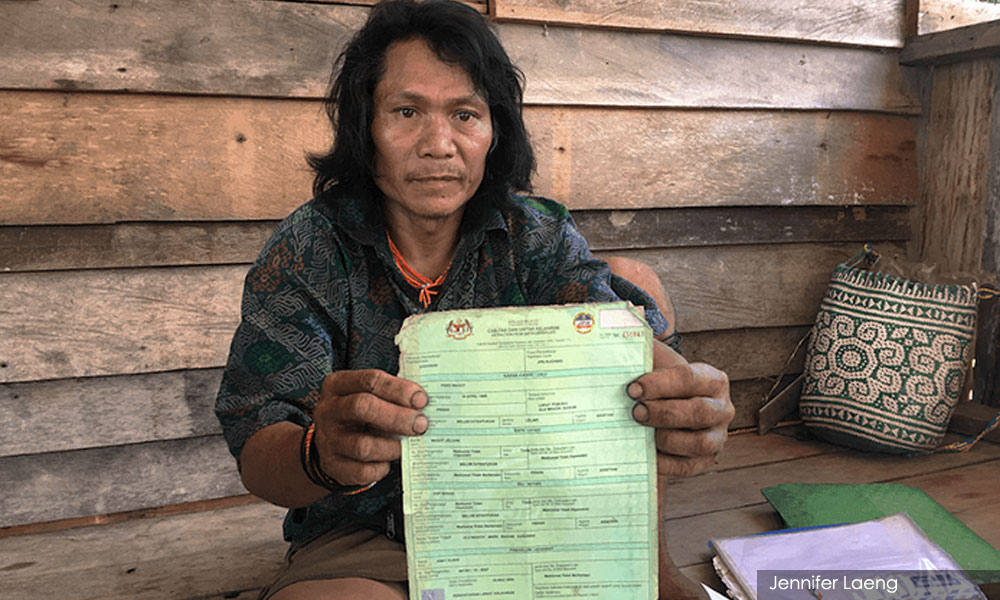

Peng Magut lives in Long Tevanga, a village at the border between the Limbang and Baram districts.

The terrain is beautiful, punctuated by the cool mountain air. But the village has no electricity, no running water, much less an Internet connection.

And without the luxury of owning a vehicle, for Peng and many others like him, it is a costly outing from the village.

Travel is expensive as there are no buses or taxis. It costs RM1,800 to charter a private four-wheel vehicle for the drive from Miri to the Baram interiors.

He said it was God-sent when a roving task force from the Miri Special Mobile Unit (UKBM) and the NRD came to the village to help Peng register his own birth for the first time more than 10 years ago. But after that, he did not receive any news about his application.

Peng, who is in his 40s, has made his application four times and after the first try 10 years ago, the next three applications saw him walking for three hours to other villages in Baram, where such registration exercises were carried out.

The last time he made a birth registration application was in 2019 but to date, he has yet to be informed of the status of his application.

“I travelled to Long Menging, Long Seridan, Long Lama, Limbang, and Pa’ Adang. We travelled to these places on foot and after all these efforts, I have not heard anything firm about my application,” Peng said in his Penan dialect.

“They would tell me that my application is being processed or... to wait for news (about the application).

“I wonder that after 10 years, what has happened to my application. They (NRD) work using computers, they should have done the work fast because we take up to two days to hunt for food in the deep jungle,” said Peng.

His wife, June Along, and their two sons Rudy and David are also waiting for news on their applications too.

While Peng and his entire family do not read or write in Bahasa Malaysia, Peng understands the importance of obtaining their MyKads.

Especially if that means being able to claim rights over ancestral land, besides a right to vote, access to education, healthcare, travel, and very basic necessities.

Awareness building

Peng’s awareness is in part because of the Penan Empowerment Network (Pena) led by Elia Bit, and their work to educate the Penan community on these issues.

“Due to remoteness, financial, and logistical issues, many of them chose not to register their birth.

“Some do not even know the importance to register their marriage especially the older generation, hence leaving their children undocumented or born stateless,” said Elia, who herself is Penan.

She said there are about 200 Penans in Baram who are either stateless or with undetermined citizenship status.

There are more than 120 Penan settlements scattered across the Baram constituency alone.

In the villages of Long Menging, Long Saliang, and Long Balau, there are at least 20 confirmed stateless Penans. But Long Mengin head Kala Konet estimates there are at least 100 more within the wider Ba’ Magoh area.

Similarly, Sarawak Dayak Iban Association Rajang (Sadia-Rajang) chairperson Bill Jugah said he has collected about 200 applications for registration of birth from the Balai Ringin, Sri Aman, and Mongkos areas since 2016.

“Most of the applications were successful. However, I do not have the exact figures because they did not inform me of their status of applications,” he said.

Jugah has also been collecting data on stateless individuals around the Sibu area.

These are persons excluded from the “official government distribution list” when he was distributing aid after Covid-19 hit the area last year.

He said another 180 stateless persons had met with him last October.

Confrontation fighters still waiting for citizenship

Meanwhile, In Lawas, some 500km away from Belaga, 80-year-old Basar Arun has been waiting for more than half a century for the government to approve his citizenship application.

Although born in what is now Indonesia, Basar had entered Sarawak through the Ba’ Kelalan border in the early 1950s for a better life.

This was before Sarawak, Sabah, and Malaya formed Malaysia in 1963.

Soon after crossing the border, he volunteered to become a border scout and served during the Confrontation with Indonesia from 1963 to 1969.

For his contribution during the Confrontation, Basar was awarded a General Service Medal with Borneo Clasp by Queen Elizabeth II.

He previously held a temporary resident card (MyKas) and was given the permanent resident (PR) status in 2013, five decades after defending Malaysia in battle.

It is not just Basar who has waited decades to be recognised as a Malaysian citizen, despite service to the nation.

Six other former border scouts - Basar Paru, Tabed Raru, Baranabas Palong @ Branabas, Joseph Pengiran, Kedimus Liling, and Sia Lupang - who served during the Confrontation are in the same boat.

All seven served as border scouts and assisted the armed forces to fight insurgents along the border area until 1974. They have been waiting for over 30 years for their applications to be approved.

They had been applying repeatedly for their status to be changed from permanent resident (PR) to Malaysian citizen but to this day, there is no light at the end of the tunnel.

Second-class bumiputera

Jugah believes that statelessness renders indigenous groups as “second-class bumiputera” and also affects the Iban, Kenyah, and Kayan.

It also impedes the indigenous from adapting to more modern life, if they choose to.

Kala and Peng said they are able to self-sustain through traditional means like hunting and gathering, but still believe it is important to be recognised as citizens.

“We began to come out of the jungle and tried to lead a semi-nomadic lifestyle in the early 1980s. Some of us have adapted to the new living outside the jungle, but some still prefer the old way of living,” said Kala.

And when they do attempt to settle down in one area, they are threatened by people who claim to own the land they are on.

Kala said there were over 20 families in Long Menging who wanted to build proper houses to live in, including himself.

But he had been receiving threats from another family from a neighbouring village. The family, from a different tribal group, claimed that Kala and the Penans were occupying their land.

“Initially, there were over 20 families here but because of the continuous threats and intimidation by those who claimed to have rights over the land, the majority of my people had no choice but to go back into the jungle. Many of them are undocumented,” said Kala.

For the organisation Lawyer Kamek for Change (LK4C), a non-profit made up of lawyers who focus on public interest litigations, there is an urgent need to establish the gravity of the situation by finding out just how many of Sarawak’s indigenous people are undocumented.

“I believe a thorough study on (the number of stateless persons) or an inquiry committee ought to be set up to study this issue,” said LK4C director Simon Siah via email.

Data not available to the public

But this is not an issue that the authorities have completely ignored.

Besides having mobile NRD units visit the rural settlements to register indigenous people, a special task force under the local Welfare, Community Wellbeing, Women, Family, and Childhood Development Ministry was set up in 2016 to assist citizenship applications for those below 21-years-old.

The task force was under the purview of Sarawak’s Minister of Welfare, Community Well-being, Women, Family, and Childhood Development, Fatimah Abdullah.

It is learnt that meetings were held every month between officials from the NRD office in Kuching and the special committee when it was still in force.

Yet, despite these efforts, up to July 2019, only 717 citizenship applications were submitted through the task force and it is not known how many were approved.

When Pakatan Harapan took over the federal government in 2018, there was a re-think of these policies.

In July 2019, then home minister Muhyiddin Yassin announced there would be a federal-level committee to handle citizenship applications, including those from Sarawak.

But the work stalled after another change of government in March 2020.

Two months ago, Fatimah said the special task force has been revived and would hold its first meeting in late April but nothing materialised.

Her office declined to comment when asked for the number of applications and their status. It also stressed that the decision on whether to approve the citizenship application lies with the NRD headquarters in Putrajaya.

When contacted, Sarawak NRD Assistant Director (Operations) Ramzi Ibrahim said such data is classified and could only be released with Putrajaya’s approval.

However, several requests for information to NRD Putrajaya went unanswered. - Mkini

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.