“Don’t be ridiculous!” is what you would say. Why not? This is because on March 6, 2025, it was reported that Malaysia’s home minister could declare any place (including a house) as a “prison” under Section 3 of the Prisons Act 1995.

This was meant to - and did spark - a heated debate: Could the home minister use his discretion to incarcerate a prisoner at a luxurious residence? Could he declare a seven-star hotel in Kuala Lumpur - or even a property in Hat Yai, Thailand - as a “prison”?

The answer is simple: No.

Why not?

Briefly, it is not a permissible form of “pardon”. That is the heart of the issue. Second, Section 3 of the Prisons Act 1995 does not authorise any “house arrest” or “home detention”. A new Act of Parliament is needed for that - and we do not have that as yet.

Third, the Prisons Act does not authorise the arbitrary declarations of certain places as “prisons”.

Let us explore why this is so.

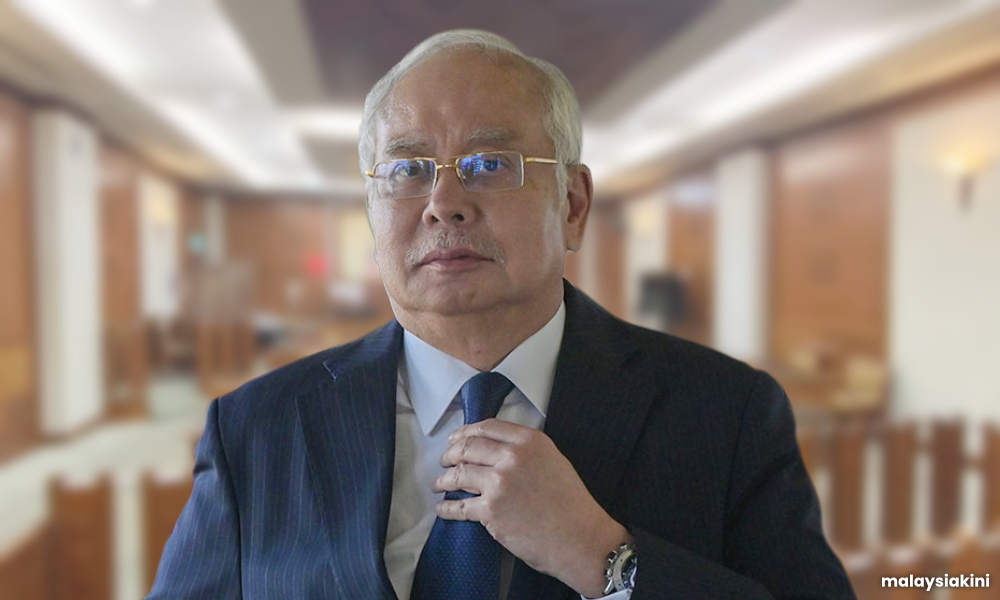

Kepong MP Lim Lip Eng MP had asked two questions in Parliament. One, if the government could declassify the meeting minutes of the Federal Territories Pardons Board. Second, if the law allowed former prime minister Najib Abdul Razak to serve his sentence at his home.

His questions resulted in the written parliamentary replies, which the press duly reported.

House arrest is already a permissible form of punishment under existing Malaysian law, with no need for new legislation, Minister in the Prime Minister’s Department (Law and Institutional Reform) Azalina Othman Said indicated.

The implication was that Section 3 of the Prisons Act 1995 would allow Najib to enjoy a residential arrest.

Is this right? For answers, we need to analyse the Prisons Act of 1995.

What does Section 3 of the Prisons Act say? Section 3 of Malaysia’s Prisons Act 1995 states:

“The minister may, …, declare any house, building, enclosure or place, or any part thereof, to be a prison for the purposes of this Act for the imprisonment or detention of persons lawfully in custody.”

The wording seems broad. But remember - the law says that even broad powers have limits. We need to understand two phrases:

“For the purposes of this Act.” (this, we shall have to discuss – and it is easy); and

“Persons lawfully in custody.” (for present purposes, that means a convict sentenced to imprisonment).

What is the purpose of the Prisons Act?

The Prisons Act was enacted to regulate imprisonment, not to create privileges for specific individuals. Its preamble states that it aims “to consolidate and amend laws relating to prisons, prisoners and related matters”.

What does this mean? It means that any “declaration” made under Section 3 must accord with the overall objectives of imprisonment as outlined in the Act and respect the punishment handed down by the courts.

What is a ‘prison’?

A “prison means any … place, … declared to be a prison under Section 3 and shall include the grounds and buildings within the prison enclosure … and used by prisoners.”

This definition makes one thing clear: a prison must function as a secure facility where prisoners are confined under strict discipline. Declaring a residential home as a “prison” would entirely contradict this purpose.

‘Temporary prisons’ have strict conditions

Section 8 allows inmates to be moved to “temporary” prisons; that too under three conditions: “overcrowding” or because of any “outbreaks of a disease”. If there are too many prisoners in one facility or an outbreak of disease renders conditions unsafe, temporary prisons may be used.

The Act also says that prisoners can be moved “for any other reason … necessary to a … temporary shelter and safe custody of any prisoner, … in temporary prisons.”

Just to be clear, “for any other reason” cannot be that one of the prisoners is a convicted former prime minister.

Even then, strict rules apply. Temporary prisons must operate as regular prisons “for the purposes of this Act.” Prisoners must return to their original facilities once conditions improve.

Their removal is strictly time-bound - limited to three months at first, and extendable up to a maximum of nine months - and no more.

Why does house arrest defeat the purpose of imprisonment?

Imprisonment serves four key purposes: retribution, deterrence, incapacitation, and rehabilitation. Central to these purposes is the deprivation of liberty and removal of creature comforts.

As Gresham Sykes noted in “The Society of Captives”, imprisonment imposes “pains” - it is the loss of freedom, autonomy, and social bonds. These are all essential components of punishment. (Gresham Sykes, Jeremy Bentham, Dr Esther FJC van Ginneke, Miranda Bevan, and Adam J Kolber, etc.)

Declaring a residential home as a “prison” undermines these principles. This allows a select group of convicts to enjoy comforts denied to other prisoners. It defeats the punitive intent behind incarceration by creating unequal treatment between ordinary prisoners and politically connected individuals.

Judicial oversight on ministerial discretion

Ministerial discretion under Section 3 is not absolute. Courts have consistently held that discretionary powers must align with statutory purposes. They cannot be exercised arbitrarily.

In Padfield v Minister of Agriculture [(968) AC 997, Lord Reid emphasised that discretionary powers conferred on ministers must be exercised in accordance with statutory objectives; arbitrary decisions are unlawful.

Similarly, in R (Anderson) v Secretary of State (2002) UKHL 46, the House of Lords ruled that sentencing decisions affecting liberty are judicial functions and cannot be overridden arbitrarily by ministers.

Malaysian courts have echoed these principles. In Pengarah Tanah dan Galian WP v Sri Lempah Enterprise (1979) 1 MLJ 135, the Federal Court ruled that executive discretion must not be arbitrary or capricious.

More recently, in Hew Kuan Yau v Menteri Dalam Negeri (2022) MLJU 1571, it was held that ministerial discretion is subject to judicial review for legality and fairness.

These cases make it clear that Section 3 cannot be interpreted as granting unchecked power to convert imprisonment into house arrest.

Deprivation of liberty remains a central principle of punishment

Deprivation of liberty itself remains broadly accepted as central to imprisonment.

Modern penal systems still rely heavily on confinement - restricting freedom of movement - as the fundamental punitive measure.

Why Section 3 should not be exploited

There is no statutory basis for house arrest under Malaysian law. Allowing such an interpretation would undermine judicial authority.

It will violate the principle of the separation of powers enshrined in Malaysia’s Constitution.

Article 121(1) vests judicial power exclusively in courts. It is the courts that have the authority to sentence convicts.

Permitting ministers unrestrained discretion to declare private residences as prisons undermines judicial independence. It allows a government to interfere with the severity of a punishment - to make it “more comfortable”.

Again, using Section 3 for house arrest creates inequality before the law.

Article 8(1) guarantees equal treatment for all citizens under Malaysian law. Favouring politically influential convicts over ordinary prisoners creates a two-tiered justice system - one for elites enjoying luxurious detention conditions and another for ordinary convicts subjected to harsher standards of incarceration.

Indiscriminate use also erodes public confidence in the administration of justice. This creates the perception - and points to the realities - of political favouritism.

The principle of the rule of law requires transparency, fairness, and impartiality in the administration of criminal justice. Any arbitrary use of Section 3 violates the “basic fabric” of the Constitution.

What can we learn from other Commonwealth jurisdictions?

In Commonwealth countries like Australia and New Zealand, house arrest is strictly regulated by a specific Act. It is also strengthened and supervised by judicial oversight, not ministerial discretion.

In Australia, Article 120 ensures uniform treatment across federal prisoners. There, ministers have no power to arbitrarily designate private residences as prisons.

In New Zealand, home detention is limited to minor offences, and it is subject to strict monitoring by probation officers.

These systems prevent abuse by ensuring transparency and accountability through judicial control, not governmental interference.

What the Madani government promised in 2024

In October 2024, the Malaysian government publicly declared that the proposed house arrest legislation was aimed at “reducing prison overcrowding” and “promoting restorative justice”, not to benefit specific individuals convicted for serious corruption offences.

Any deviation from this stated intent would constitute an improper use of legislative authority.

Conclusion

Section 3 of the Prisons Act 1995 cannot be interpreted as granting unchecked power to convert imprisonment into house arrest. Such misuse violates constitutional principles like separation of powers and equality before the law while undermining public trust in justice administration.

True service to the nation requires integrity, not privileges or excuses for corruption. Courts have consistently rejected claims of national service as mitigating factors for corrupt leaders; policymakers should do the same.

Let justice prevail over favouritism and let Section 3 serve its intended purpose - proper administration of prisons, not political convenience. - Mkini

GK GANESAN is a lawyer and an international commercial arbitrator.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of MMKtT.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.