On Feb 21, eight years have lapsed from the completion of the previous redelineation exercise of Sabah (2017). Hence, the Election Commission (EC) may choose to start the redelineation of Sabah anytime.

When the topic of electoral boundaries is raised for Sabah (and Sarawak too), the conversation can quickly be directed to the call for one-third representation in Dewan Rakyat. However, such conversation distracts from the real issue in Sabah - current electoral boundaries that discriminate against Sabahan voters.

Overview

In August 2016, the Sabah state assembly passed legislation to increase the state seat count from 60 to 73. In the following month, EC commenced the redelineation for Sabah which altered the boundaries of parliamentary and state constituencies.

The number of parliamentary constituencies remained the same - 25 - and 13 new proposed seats showed up in the redelineation drafts.

Unlike the significant pushback faced in the concurrent redelineation exercise of Peninsular Malaysia, EC was able to complete two rounds of redelineation drafts by January 2017 (inclusive of local inquiries) and submitted the redelineation report to then-prime minister Najib Abdul Razak.

Due to the vagueness of the 13th Schedule of the Federal Constitution (which guides the redelineation process), Najib did not table Sabah’s redelineation report for parliamentary approval immediately. When a general election was called in 2018, the number of state seats contested remained at 60 for Sabah.

Only after change of federal government, then-prime minister Dr Mahathir Mohamad tabled the redelineation report in 2019 for Parliamentary approval. Seventy-three state seat count was finally used for the 2020 Sabah state election.

With the introduction of Undi18 and Automatic Voter Registration (AVR), around 485939 Sabahan voters were added into the electoral roll.

Let us examine the consequences of the Sabah’s 2017 redelineation exercise. The focus will be more at the DUN level as the alteration of parliamentary boundaries for the said redelineation exercise was limited.

Malapportionment

In 2022, the state constituency with the largest electorate was Kapayan (47605 voters) and the smallest constituency for the electorate was Banggi (9127 voters). Kapayan represents an area under Greater Kota Kinabalu while Banggi covers the largest island in Malaysia.

It is no surprise due to vagueness of 13th Schedule gave more voting power for a rural constituency like Banggi while Kapayan was placed at disadvantaged. While EC is required to equalise electorate count among constituencies within the state, an exception was given for constituencies in rural areas.

This creates opportunity for malapportionment (the inequality of voting power strength). With the introduction of AVR, there are strange twist to the malapportionment problem.

Beneficiaries

When AVR was introduced in 2018, all constituencies experienced a growth ranging from slightly over 1000 new voters (Api-Api) to over 16 000 new voters (Inanam). The constituency that experienced slowest growth in Sabah due to AVR was Api-Api (Kota Kinabalu). Api-Api represents the older part of Kota Kinabalu while Inanam is home to many new housing estates.

During the 2017 Sabah’s redelineation exercise, Api-Api was five percent above the average state constituency size of Sabah. In the 2020 state election, with a rising electorate, it became oversized (24 percent above the average).

With AVR implementation, Api-Api became 17 percent below the average state constituency size of Sabah. Inanam, on the other hand, was oversized during the redelineation exercise (68 percent above the average size) and now it 86 percent above the average size.

In another context, Api-Api’s voters have two times the voting power of Kapayan, the most populous constituency in Sabah. These constituencies are urbanised.

In the Sandakan region, we have similar situation where Tanjong Papat (which is home to older part of Sandakan) started off as equal sized constituency during the redelineation review and now became constituency with a lot of voting power.

Constituencies such as Sungai Sibuga and Elopura which is home to many housing estates witness continued or worsening voting power. All these constituencies are urbanised.

When state constituencies are examined by the median household income, malapportionment not only pit voters based on urbanisation level, but also discriminate voters on income levels.

Tindak Malaysia advocates state constituencies to have an electorate size within +/-20 percent of Sabah’s state electoral quota - EQ (average size of the state constituency).

If one were to map out the distribution of constituencies based on share of EQ and median household income, the voters who reside in lower income constituencies are beneficiaries of the malapportionment. Twenty-one state constituencies in Sabah (as of 2022) should be deemed undersized where the constituencies have too little voters.

The vast majority of the constituencies are rural in nature and record levels of prevalence of absolute poverty. Close to 60 percent of the households in Banggi are below absolute poverty.

While this gives an advantage in terms of representation for the poorer voices, small constituencies can be largely influenced by politics of money and amount of effort to swing those constituencies are minimal.

Considering nearly half of the constituencies in Sabah are deemed rural while the Sabah has the majority of its population in urban areas, malapportionment benefits poorer voters if they happen to live in rural settings.

In short, the winners of the malapportioned constituencies are voters residing in the inner, ageing core of the cities (like Kota Kinabalu and Sandakan), rural and poorer constituencies.

Losers

Primary losers of the malapportioned constituencies in Sabah are voters who reside in urban areas. However, we must make a distinction between the types of urban constituencies that benefit and lose in terms of voting power thanks to the implementation of Undi 18 and AVR.

We must acknowledge that the 2017 redelineation exercise barely addressed the large electorate sizes of urban constituencies such as Tanjong Kapor (Kudat area), Luyang (Kota Kinabalu area), Elopura (Sandakan area) and Sri Tanjong (Tawau area).

A voter in Kapayan for the 2020 elections had a voting power of 1/5 of Banggi. With the introduction of Undi18 and AVR, different set of losers emerged. Voters who are residing in Greater Kota Kinabalu and Sandakan such as Karambunai, Darau, Inanam, Sungai Sibuga and Elopura largely witnessed an erosion of voting power.

Within Kota Kinabalu (complete urban scene), voters of Luyang have voting power nearly half of the voters of Api-Api and Likas.

Another group of voters who are at the losing end of the malapportioned constituencies are the voters in higher-income constituencies. There are 25 out of 73 state constituencies in 2022 where the constituency’s median household income is higher than Sabah’s median household income level (RM4,577).

Constituencies that exceeded 20 percent of Sabah’s EQ are largely urban and high-income constituencies. However, we need to include a caveat. High-income areas like Segama in Lahad Datu and Elopura in Sandakan have significant households under absolute poverty levels, with Segama at 25.5 percent and Elopura at 19.5 percent.

If you happen to be a B40 residing in Segama or Elopura, your voting power is much lower than B40 of Likas (urbanised) or a rural B40 in Banggi (rural).

In summary, the losers of Sabah’s unequal constituencies are the voters residing in suburban and growing urbanised territory of major cities and voters residing in higher income constituencies.

For key demographics data for Sabah state assembly for 2020 and 2022, please head to Tindak Malaysia’s Github site.

Gerrymandering/violation of local ties

In August 2016, the Sabah state assembly added 13 new seats to its composition. Ideally, these new constituencies should have been created in more populous areas of Sabah and effectively address the malapportionment problem.

Thirteen new constituencies formed during the redelineation reviews of 2016 indicated a particular bias in their nature. If we were to examine the polling districts that make up the new constituency using GE13 results, it was clear that majority, if not, all the 13 new seats favoured then ruling coalition of Sabah – BN.

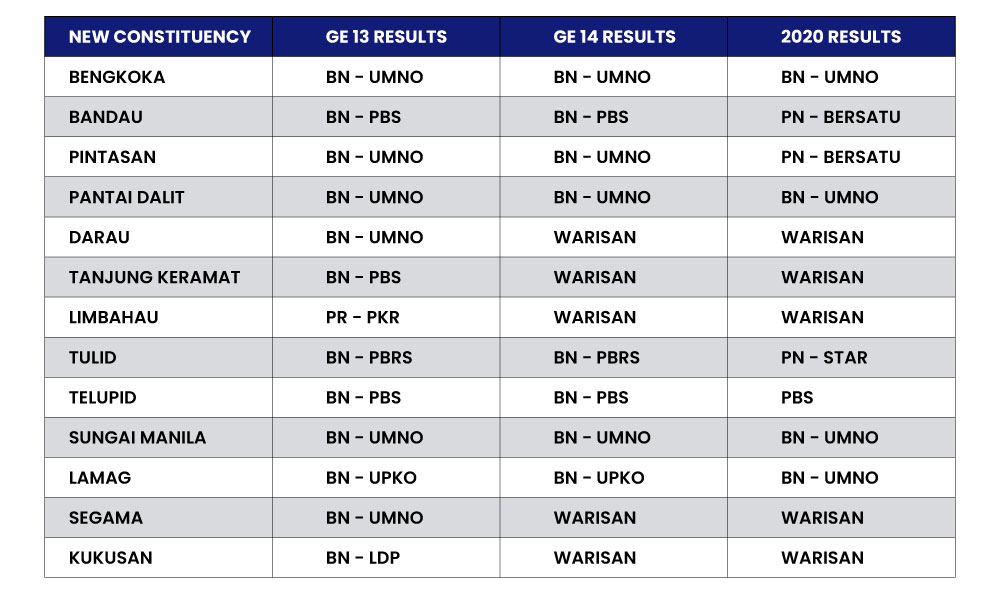

The table below shows the projected winners of 13 new seats using GE13 and GE14 results and actual winners for the 2020 election:

When the Sabah’s redelineation review as going on, a new party emerged in Sabah - Warisan (formed in October 2016). This party, led by Shafie Apdal, appealed strongly to Bajau-Suluk communities and to certain degree, Malay voters leading up to GE14 (2018). This could explain, five out of 13 proposed constituencies would have won by Warisan.

The emergence of Warisan may have resulted Sabah’s redelineation report not to be tabled under the BN government. With the change of state government in 2018, reconfiguration of alliances and collapse of Warisan-led government in Sabah, the 13 new state constituencies are no longer domain in one single coalition.

This can be seen that four state constituencies were won by BN-Umno (2020). In Sabah, redelineation exercises, historically, that uses political calculations have limited effects due to ever shifting alliances and parties.

The 2017 redelineation exercise also missed out the opportunity to rectify irregular shaped constituencies.

Let’s look at three examples. Tanjung Aru (Putatan) is composed of the mainland Sabah (home to Kota Kinabalu International Airport and Sembulan area), Pulau Gaya and islands (near and distant from the coast). The whole constituency is within the same district of Kota Kinabalu.

However, Pulau Gaya is connected to mainland Sabah via the ferry links in Likas (Kota Kinabalu). Hence, any assemblyperson or MP of Tanjung Aru/Putatan have to exit the constituency, enter Kota Kinabalu parliamentary seat and take ferry to Pulau Gaya.

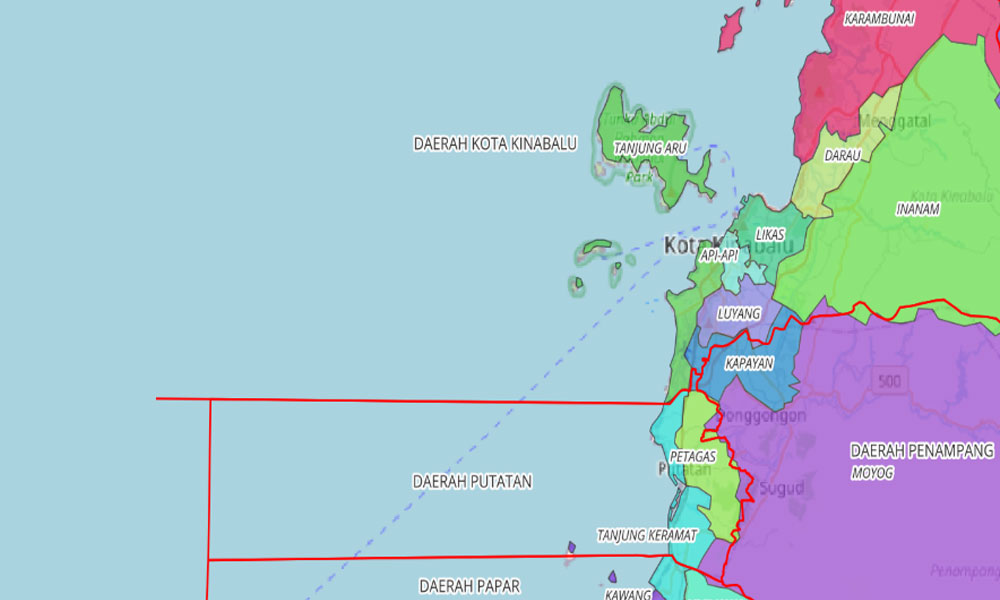

The second example would be Tanjung Keramat (Putatan). Tanjung Keramat is one of the 13 new state constituencies, and it has two parts (the northern area close to Putatan town, and the southern area which is home to the army camp and Lok Kawi areas).

In the process of creating this new constituency, Tanjung Keramat (Putatan district) included an area in Papar district (Lok Kawi area). More importantly, the southern and northern parts of this new constituency are connected viaa thin neck which hugs Jalan Putatan.

This raises the question of whether local ties within the Putatan district were taken into account for the formation of the constituency.

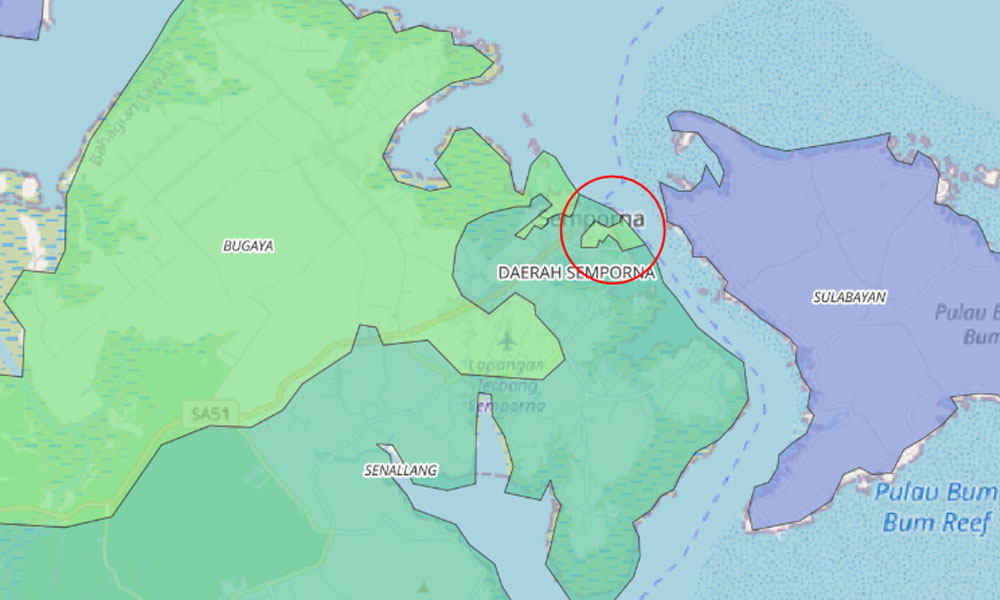

Going to the east, Bugaya, which did not experience any boundary changes during the redelineation exercises, has an unaddressed exclave. This exclave covers part of Semporna township. Bugaya of the period of 2003-2016 did not have an exclave.

However, during the stealth redelineation exercises of 2016 (involved redivision of polling districts and illegally altering state and parliamentary boundaries), Simunul polling district of Bugaya became detached and became an exclave of Bugaya.

Later in the year, the EC decided not to do anything to rectify the exclave. This is a clear violation of local ties when Simunul is completely surrounded by another constituency (Senallang) and has no connection to Bugaya.

All these examples point to that the 2017 redelineation exercise failed to create constituencies that upheld one of the principles of 13th Schedule - respecting local ties.

What can you do?

Since eight years have passed from the previous exercise, it is crucial for Sabahan voters to prepare themselves for any future redelineation exercises.

When a redelineation notice is issued via the Gazette and at least one newspaper in the constituency, there is a 30-day window for voters to study the proposal, analyse the points for objections or endorsements and mobilise 100 voters or more.

Since it’s a short period of time, it is important the mobilisation of potential redelineation objectors should take place earlier. We, Tindak Malaysia, is doing continuous recruitment of redelineation objectors. We will notify you within a month or two whether you have met our redelineation objector criteria.

Secondly, demand the state and federal government to allocate more funds and carry out infrastructure projects to improve physical and network connectivity especially in the rural constituencies.

The issue of connectivity in Sabah came to prominence during the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020 when a rural university student, Veveonah Mosibin had camped on a tree to access the internet for her studies.

One of the reasons why malapportionment is allowed in the Malaysian context is the rural constituency has been given the exception to the equalisation rule.

The 13th Schedule 2 (c) states that “the number of electors within each constituency in a State ought to be approximately equal except that, having regard to the greater difficulty of reaching electors in the country districts and the other disadvantages facing rural constituencies, a measure of weightage for area ought to be given to such constituencies”.

Some of the Sabah’s constituencies are huge in area and beset with physical communication difficulties. Addressing the “difficulty of reaching electors” is beneficial for state economy and remove the reason of exempting equalisation rule for rural constituencies.

Thirdly, for the large area constituencies such as Lamag, Labuk and Sukau, the Sabah state assembly needs to allocate dedicated funds for assemblyperson service centres to service the vast constituency.

Similarly, the Dewan Rakyat should do similar funding for MP service centres for large areas such as Kinabatangan, Beluran and Lahad Datu.

Sabahan voters should demand the state assembly and Dewan Rakyat to push for more funding for the service centres so that Sabahan voters greatly benefit from better access to elected representatives.

Fourthly, push for new equalisation limits for Sabah’s state and parliamentary constituencies. Acknowledging large areas and limited infrastructure connectivity, we propose a deviation limit of +/-20 percent from Sabah’s EQ for state and parliamentary constituencies. If there are any exceptions to be given, these exceptions must be transparently communicated to the voters and other stakeholders.

Conclusion

Now that we have established the long-term impact of the Sabah’s 2017 redelineation exercise, we need to ready to respond now till the conclusion of the next redelineation exercise. You can start registering yourself as Redelineation Objector today.

Start pushing for greater infrastructure improvements in Sabah. Demand Sabah state assembly and Dewan Rakyat to provide better support for elected representatives in rural areas.

Finally, work towards greater equalisation of constituencies. Ultimately, we want fair redelineation that respects Sabahans irrespective of ethnicity, age, class and political preferences. - Mkini

DANESH PRAKASH CHACKO is the director of Tindak Malaysia.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of MMKtT.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.