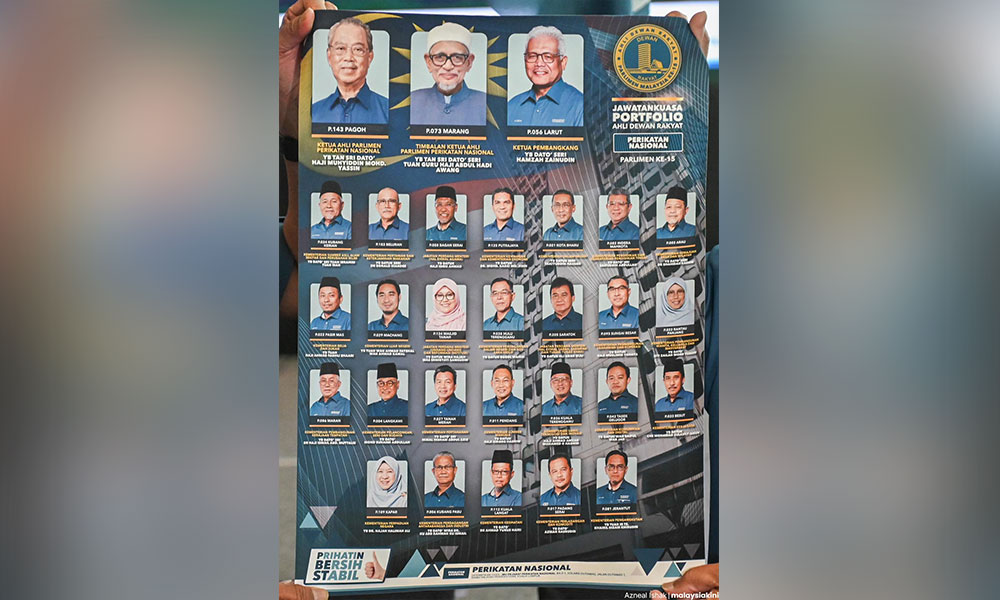

Perikatan Nasional announced its shadow cabinet line-up on Feb 2. Let’s explore eight pertinent questions on the matter.

1. Why are there no Chinese and Indian shadow ministers? Why so few women ministers?

Many people’s first response to PN’s shadow cabinet was that it cannot possibly serve a multicultural Malaysia well because it is predominantly Malay Muslims, with only one non-Muslim bumiputera each from Sabah and Sarawak, and not a single Chinese or Indian.

Such criticisms are driven by either ignorance of what shadow cabinet means and how it works, or enmity against PN.

A shadow cabinet must consist of MPs primarily from the Lower House. Ronald Kiandee (Beluran) and Ali Biju (Saratok) were made shadow ministers because they won their seats for PN.

PN did nominate a total of 24 Chinese and eight Indian candidates (19 under Gerakan, 12 under Bersatu and one under PAS) but all lost to Pakatan Harapan. If any one of them won, they would surely be appointed as shadow ministers like Ronald and Ali. Do the critics want to trade in any Harapan parliamentarian for a Chinese/Indian shadow minister from Gerakan/Bersatu/PAS?

A similar complaint is that the shadow cabinet has only three (10.71 percent) women out of 28 ministers and lower than the five (17.86 percent) in Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim’s cabinet.

This criticism is more valid because PN nominated only 15 women candidates (seven each under PAS and Bersatu, one under Gerakan) and won only six (five under PAS and Mas Ermieyati from Bersatu). Had PN nominated more women, especially in the north, it would have more women MPs to choose for its shadow cabinet.

Nevertheless, having three shadow ministers out of six women MPs gives PN an inclusion rate of 50 percent, higher than Harapan’s 33.33 percent (five ministers out of 15 women MPs).

2. Why not appoint Chinese and Indian senators as shadow ministers?

PN has not revealed the reasons why it did not appoint senators to its shadow cabinet. It has two Chinese from Gerakan including president Dominic Lau, one Indian from PAS N Balasubramaniam, and one Malay woman from PAS.

Politically, their exclusion embarrasses Gerakan and PAS’ non-Muslim supporters’ wing, showing that they are entirely ornamental. Our cabinet has ministers from the Senate. So do shadow cabinets in UK and Australia.

PN’s decision to pick only MPs as shadow ministers, however, may be justified for effectiveness because our Senate is a rubber stamp with much less ministerial and media attention, unlike its counterparts in Australia, UK and Canada.

While ministers from the Senate can attend both houses of Parliament to be questioned, shadow ministers from the Senate would be confined to the Upper House to wait for ministers to appear.

3. Are these shadow ministers competent?

This question presumes that a shadow cabinet is an option upon the availability of talents, and fails to recognise that it is a necessity to produce a division of labour amongst senior opposition MPs.

Just consider analogously the real cabinet: would a new government not appoint ministers because they lack experienced and competent MPs? Ministerial positions have to be filled primarily by Lower House MPs, whether or not there are sufficient talents. Inexperienced ministers just have to learn on the job and many still do well.

The opposition cannot change the talent pool of its MPs before the next election. With a shadow cabinet, its senior MPs get to develop policy expertise and coordinate policy positions across different policy domains.

For example, a Covid policy concerns not just health, but also the economy, human resources, education, tourism and transportation.

What if the shadow ministers sleep on the job? Then the shadow cabinet fails but it can’t make it worse for the opposition.

However, the opposition can reshuffle its shadow cabinet from time to time, just like the government can reshuffle its cabinet. Incompetent shadow ministers can be removed and replaced by better-performing opposition backbenchers.

Hence, the shadow cabinet incentivises opposition MPs to do policy work by dividing them into the front bench and back benches, like the premier league and lower leagues in sports clubs.

4. How is it different from previous attempts by Pakatan Rakyat, BN and Harapan?

Pakatan Rakyat announced 25 “front bench committees” filled up by all its 88 MPs on July 9, 2009. Pakatan categorically denied it being a shadow cabinet because it did not want to name ministers.

So, every ministerial portfolio was shadowed by three MPs, one each from PKR, PAS and DAP, and the Prime Minister’s Department was shadowed by 18 MPs. Hilariously, Pakatan called them “front bench committees” when there was no one left to constitute the opposition backbench.

Nine years later, on Sept 26, 2018, BN announced its shadow cabinet. Like Pakatan, all its 51 MPs became frontbenchers in 27 committees, with no one left behind as a backbencher. A slight improvement from Pakatan, the 51 frontbenchers were divided into 27 shadow ministers and 24 deputy shadow ministers.

On May 9, 2021, Harapan announced a line-up of committees, which was eventually expanded to 12 – only 11 for ministerial portfolios and one for mobilisation, each with three to 12 members per committee. A total of 75 names were listed: 50 out of Harapan’s 90 MPs (56 percent), one senator, nine state assemblypersons and 15 party leaders and think tankers.

The bloated structure and the “leave no one behind in backbench” mentality guaranteed the failure of these attempts.

This round, PN deserved to be credited for understanding what a “shadow cabinet” is – by definition, it must be complemented by an opposition backbench – by leaving 46 of its MPs as backbenchers.

Unlike Harapan, it did not evade the thorny question of portfolio allocation – both PAS and Bersatu get 14 seats even though PAS constitutes 58 percent of PN’s parliamentary strength.

5. Will they have weekly meetings?

Ultimately, a shadow cabinet is a coordinating device for the opposition. Like the cabinet, they must meet weekly to coordinate their policy position and collective response to current affairs.

If carried out, the weekly meeting feature will make the shadow cabinet the real centre of power, replacing PN’s presidential council. Like it or not, it would make the opposition more policy-conscious and less a mere collective of ceramah speakers.

With the institutionalised weekly meetings, the shadow cabinet will function – albeit sub-optimally – even if it is denied any resources and access to government information. Without the weekly commitment to cross-portfolio coordination, the shadow cabinet will fail, even with resources and information access.

Instead of dismissing its composition, the media and the public should press the PN shadow cabinet for its weekly meeting date and its first meeting.

6. Will it strengthen the green wave?

The dismissal of the shadow cabinet by some government politicians and supporters – preliminary non-Malays and liberals – reflects more on the latter’s anxiety about the rising green wave than the former’s shortcomings.

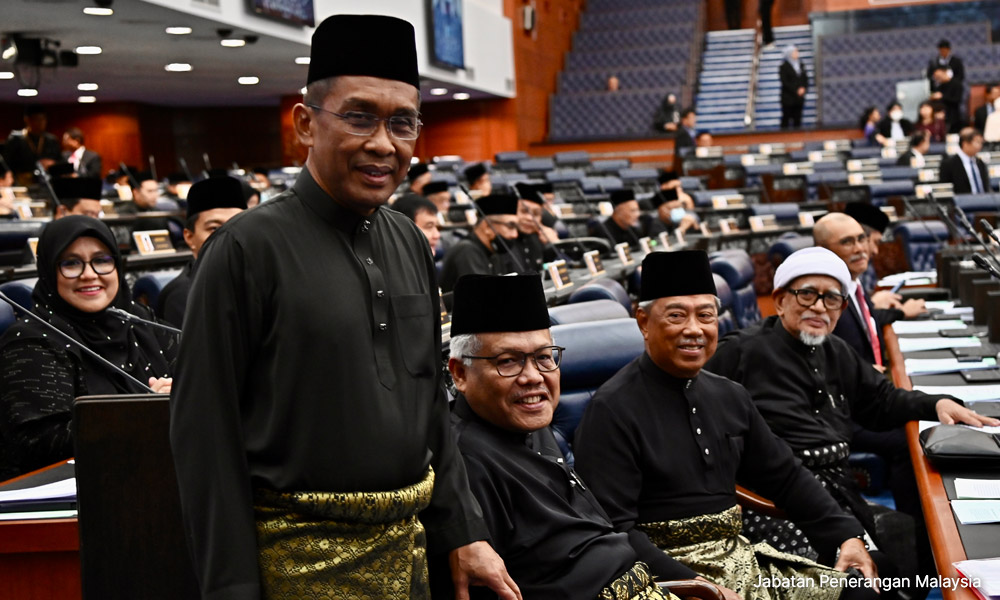

In contrast, two Malay ministers – Minister in the Prime Minister's Department (Law and Institutional Reform) Azalina Othman Said (Umno) and Domestic Trade and Cost of Living Minister Salahuddin Ayub (Amanah) welcome its formation.

Many non-Malays fear that the formation of the shadow cabinet will make the green wave less stoppable, hence any improvement in PN’s policy competence will cost the minorities more of their religious freedom.

They don’t realise PN’s advance is largely due to the Malay swing voters’ denouncement of Umno’s corruption and distrust of Harapan. As long as these two factors do not change, the green wave would march on, with or without the shadow cabinet.

7. Can it benefit the coalition government?

While the shadow cabinet might improve PN’s standing in the eyes of investors and the international community, it will also allow Anwar’s coalition government to pursue its policies with fewer distractions on ethnoreligious grounds and reduce the risk of a Sheraton Move 2.0.

With policy specialisation, PN lawmakers cannot simply fire potshots at every minister without offering their own alternative policy.

For example, Wan Saiful Wan Jan (shadow communications and digital minister) now has to compete with Communications and Digital Minister Fahmi Fadzil on 5G and internet cost, not with Local Government Development Minister Nga Kor Ming on drawing advice from Singapore’s Housing & Development Board (HDB).

Shadow local government development minister Ismail Abdul Muttalib can continue to pursue the HDB polemics, but Nga, the media and the public can ask for his superior policy in better preserving Malay reserves lands - which PN, curiously, did not pursue when in government in 2020-2022.

If the shadow ministers are to be sworn in before the king as His Majesty’s loyal opposition, they would also be politically constrained from actively plotting to bring down the government before 2027.

8. Why is paying shadow ministers a good investment for democracy?

Many Harapan supporters reject calls to pay shadow ministers a fraction of the minister’s salary, like Australia does, thinking that it would be a waste of public funds.

They don’t realise that what makes ministers expensive is not their monthly salary (RM14,907.20) but all the allowances, pensions and their entourage of aides combined. To emulate Australia, a shadow minister would be paid only one-third of the minister’s salary or RM5,000, without allowance or pension.

This amount would immediately raise the public expectation of shadow ministers and induce a more balanced comparison between the government and the opposition.

Without comparison, ministers’ underperformance or blunder tends to be overplayed without considering viable alternatives.

If PN’s shadow ministers do a good job, then they completely deserve the extra RM5,000. If they sleep on the job, the RM5,000 is then the advertisement that they would be unfit as ministers.

Saving that RM5,000 would be penny-wise but pound-foolish. Unless one is possessed by their fear of the green wave, is the merit of this small investment so hard to understand? - Mkini

WONG CHIN HUAT is an Essex-trained political scientist at Sunway University. He is a professor at the university’s Sustainable Development Solutions Network (SDSN) Asia. Mindful of humans’ self-interest motivation while pursuing a better world, he is a principled opportunist.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of MMKtT.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.