HISTORY | Malaysian historiography of the British colonial era has been largely conceptualised in terms of official colonial narratives.

Such sources are only relevant in terms of the political and economic histories of the colonial administration. Other than being able to narrate a series of permitted versions of historical events, they shed little light on the complexities of a colonial environment and the varying perspectives on it.

Non-official accounts of the Malay Archipelago can contribute to a more complex history of colonial Malaya, particularly the region's pre-1874 intervention history. Writings by merchants, travellers, and missionaries in the 18th and 19th centuries tell us about the history that colonial officials did not record, as well as more about the history of official colonialism itself.

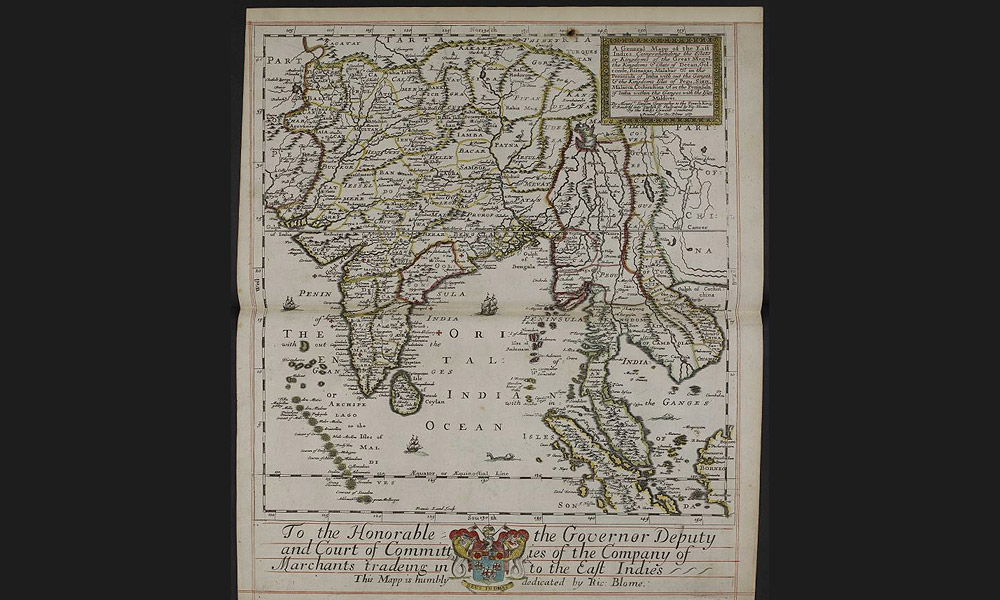

In the 16th and 17th centuries, the emergence of nation-states in Europe and the mercantile political economy heralded the age of exploration. In Asia, merchants actively sought spices, gold, and silver. This pursuit was led by the English East India Company (EIC), the Dutch East India Company (VOC), and the French East India Company.

The English East India Company, whose trading activities set the stage for British Malaya's colonial history, left a wealth of source materials for scholarship not only on imperial trade and politics, but also on local history. Known as country traders, the merchants, who included famous names such as James Scott, Francis Light, and Thomas Forrest, are generally believed to have furnished the colonial government with knowledge of the situation of the Malay Archipelago in the 18th and 19th centuries.

Especially without Francis Light, historians would have known far less about the Malay states in the 18th century. In a letter to the Governor General of India, Lord Cornwallis, dated Jan 7, 1789, for example, he provides an extensive impression of the Malay states around Penang and their economic products.

Merchants’ reports

The Malay states were pictured as greatly flourishing in merchants’ reports to the colonial government of India, which was then the epicentre of British Asian colonialism. Captain Alexander Hamilton, for example, revealed that China obtained some of its pepper and gold from Kuala Terengganu. He also noted Terengganu's regional integration. Chinese merchants were constantly present, and Terengganu rulers were forming economic ties with Siam, Cambodia, and Sambas (West Kalimantan).

Captain Joseph Jackson, another important country trader, drew a parallel between Terengganu and Coromandel and Malabar in India while stopping in Terengganu on June 14, 1764.

The extent to which the Malay rulers adopted an accommodating trading policy with a political mind would be a significant contribution to the historiography of the Malay states through the sources of English traders. While they had to conform to the Dutch monopolistic attitude by only selling products to them, the Malay rulers were said to have struck a deal with English traders who were willing to offer a higher price on some produce.

It would seem that the English traders were aware that at a time when the Malay rulers sold tin to the Dutch at price levels mandated by the latter and were unable to conduct trade with anyone other than the Dutch, the Malay rulers craftily used their link with the English to purchase firearms, for example, from James Scott.

The English traders would therefore have expected that it was through their laissez-faire policy that the rulers were able to prevent a total intervention by the Dutch and a Dutch subversion of the local economy. Yet, historians were able to see that this was not entirely true. They detected that through the accounts of British traders, colonial officials did learn that such a policy was already in operation in the Malay states.

In his article published in the ‘Journal of the Indian Archipelago’ in 1850, G Winsdor clearly listed all the ports in the Malay Archipelago that practised laissez-faire policy. Stamford Raffles himself stated that the Malay Archipelago "had long collected at certain established emporia; of this Achean, Malacca, and Bantam were the principal."

Clearly, the English traders understood that they, like other European traders before them, did not create new trade routes, but rather took advantage of existing ones that had been established long before Europeans arrived. These would include the active trade zones around Malacca, Aceh, Pasai, Bantam, Macassar, and Ayudhya in the 18th century.

Travellers’ tales

Besides traders, there were also travellers who, in either official or unofficial capacities, provided a tonne of knowledge about the Malay states. They detailed their impressions of the inhabitants, landscape, and events they observed, particularly in the Malay states of the 18th and 19th centuries.

Isabella Bird's 1883 memoir, ‘The Golden Chersonese and the Way Thither’, is a classic example of this. Although her views may appear blatantly racist by modern standards in many places, she was undeniably gifted with excellently perfected observation and characterisation skills.

In fact, when she described the inhabitants, she encountered during her stay in Malaya in 1879, Bird appears to be merely an objective observer and recorder. When describing the Malays, she viewed them as being enlightened and civilised because they lived in “houses which are more or less tasteful”, “are a settled and agricultural people”, “skilful in some of the arts” and “have a literature”.

Bird also knew that the Malays had already “possessed for centuries systems of government and codes of land and maritime laws”. She saw the Chinese as “commercial rulers of the Straits”, echoing Light's view of them as “the only people of the East from whom a revenue may be raised without expense and extraordinary effort of government”.

Pertaining to the ‘Klings’, the Indians of the Coromandel Coast, Bird described them as being “active and industrious” and were “splendid boatmen”. Bird even recognised the role of Yap Ah Loy as being “the creator of the commercial interests of Selangor” and “a most successful administrator in the populous district entrusted to him”.

Regarding JWW Birch's assassination in Perak, Bird never failed to register her thoughts. To her, this was due to the British failure to honour and manoeuvre in accordance with local sensibilities.

There was also George Windsor Earl, a British captain, colonial official, lawyer, linguist, antiquarian, and writer who toured the Malay Archipelago extensively. His account of his voyages around Southeast Asia, including Terengganu and Singapore, is published in 1837 as ‘Eastern Seas’. He documented these countries' abundant natural resources and commerce, as well as the multicultural local population.

He also wrote several articles for the ‘Journal of the Indian and Eastern Archipelago’. By conveying useful insights about the region and the affairs of local inhabitants in whom he had a deep interest, his writings to the journal formed an important corpus of colonial knowledge. They could all be viewed as stimuli for the advancement of Western colonisation in Southeast Asia.

Howard Malcom, an American educator and a Baptist minister, is another important traveller. Among other observations on local sensibilities, his accounts show how piracy was a form of economic culture. According to him, the Malays regarded piracy as honourable, and many of their princes openly took part in it. He also revealed the Malay Archipelago's economic diversity by detailing the types of products collected by local traders through a long-established free trade culture, such as camphor by the Bataks, pearls by the Sulus, and bird nests by the Malays.

Colonial missionary sources

Another type of historical source is those produced by Christian missionaries as part of their mission to Christianise Malaya's natives and immigrant population. The London Missionary Society, which was founded in London in 1795 with the goal of propagating Christianity to all people and nations, publishing and distributing religious texts in the vernacular, and teaching children and youth to read and write in school, was one notable example.

Missionaries were encouraged to write Christian books, propaganda and text. The London Missionary Society of Malacca, founded in 1815, produced sources in the form of religious and non-religious publications through its ‘Mission Press’. Such sources, which were mostly circulated in the form of tracts, broadsheets, and books, are especially useful for explaining not only the operation of cultural colonialism but also local responses to extraneous materials.

Rev Thomas Beighton's (1790-1844) controversial publications such as ‘Comparison of the Religion of Jesus with the Religion of Mohammed’, ‘The Rise of Christianity’, and ‘Spiritual Lessons’ are insightful in determining the extent to which civilising activity was intrinsically colonial. As Milner pointed out in his book, ‘The Malays’, such missionary sources can be viewed in the context of the 19th-century “ideological assault waged by the Europeans”.

Colonial missionary sources also offer perspectives other than official views on historical events. One good example is John Henry Moor, Master of the Free School of Malacca, who obtained permission from the Resident Councillor of Malacca to publish the ‘Malacca Observer’ from September 1826 until October 1829. Moor appeared to disagree with the government mission in Naning, which sought tribute from the Minangkabau people of Naning, a Malay state near Malacca. Moor's opinion cost him the job. This explains official colonialism and Christian missionaries were obligated to undertake colonial responsibilities.

To conclude, it is evident that merchants, travellers, and missionaries have made significant contributions to the historiography of Malaya and the Malay Archipelago. Despite the fact that most of their accounts reflect a raw colonial attitude, they can all be considered historical sources for the study of the Malay Archipelago. In any case, the non-official accounts paint a vivid picture of the unfolding of informal colonialism, alongside formal colonialism. - Mkini

SIVACHANDRALINGAM SUNDARA RAJA is a professor at the Universiti Malaya’s History Department. He is a well-known scholar in the field of Malaysian economic history, with numerous local and international research publications to his credit.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of MMKtT.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.