The Progressive Wage Model (PWM) could be on the verge of being adopted in Malaysia. This voluntary, incentive-based, and productivity-linked policy aims to address pressing issues such as low wages, income disparity, and low productivity.

The PWM, which was said to have improved income gaps, job quality, and productivity in sectors like cleaning, security, and landscaping in Singapore, is slated to be presented by Economy Minister Rafizi Ramli via a tabling of a white paper tomorrow.

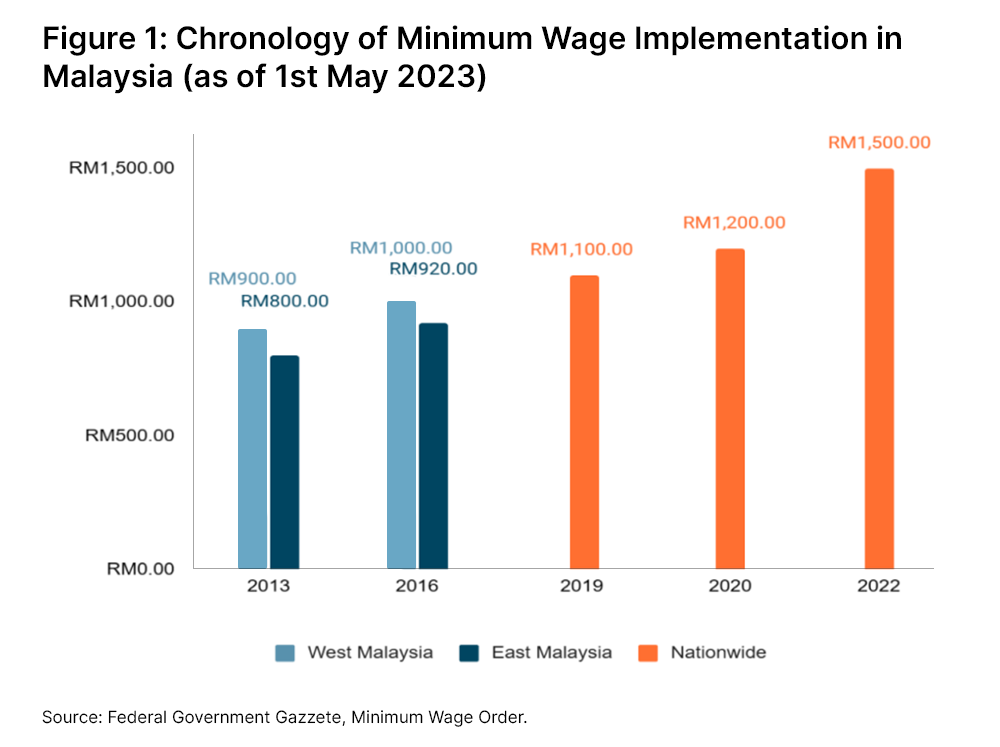

Malaysia's wage landscape, influenced by factors like recent currency devaluation, escalating youth unemployment, and heavy reliance on foreign labour, primarily relies on the Minimum Wage Model.

Despite the recent increase to RM1,500 per month with annual rises of 5.24 percent for Peninsular Malaysia and 6.49 percent for Sabah and Sarawak since 2013 recorded, overall labour productivity only managed a 2.3 percent annual increase from 2013 to 2022.

This disparity between consistent minimum wage growth and slower productivity escalation poses indirect risks of potential job losses or underemployment in the long run.

Could the PWM provide a solution or bring about a positive impact on our wage landscape?

Unlike the Minimum Wage Model, which applies universally regardless of skills and experiences, PWM allows workers to progress up the wage scale as they acquire necessary skills, and experiences, and demonstrates improved job performance.

This model is primarily implemented in Singapore as a targeted approach to selected sectors which kickstarted in three mandatory industries (cleaning, landscaping and security).

In theory, the PWM should benefit employees as it focuses on skills upgrading, productivity improvement, career advancement, and wage progression.

It provides a clear pathway for career progression and wage increases for workers in pre-specified sectors, based on their training and productivity improvements.

For employers, it indirectly contributes to long-term business profits through improved productivity, standards, and service quality.

Potential impacts, roadblocks

The main elements of the PWM stated by Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim post chairing the National Economic Action Council (MTEN) was that it will be a voluntary, incentive-based and productivity-linked model.

The Malaysian Employers Federation (MEF) remains cautiously supportive, stressing the need for the PWM to augment productivity alongside wage increases.

MEF president Syed Hussain Syed Husman asserts that the PWM must take into account the interests of businesses. He warns against burdening businesses with higher wages without a corresponding increase in productivity.

The potential success of implementing the Progressive Wage Policy hinges on pivotal factors. Firstly, its voluntary nature makes business adoption a crucial factor; widespread participation is necessary for a significant impact.

Secondly, the policy's reliance on skill enhancement necessitates accessible training programmes for workers. Thirdly, establishing clear and equitable metrics for productivity measurement across diverse sectors is essential.

Finally, government support is pivotal for mitigating possible employer resistance and ensuring policy efficacy.

In Malaysia, a significant portion of the workforce earns less than RM5,000, with 75.7 percent of the 6.45 million formal employees falling into this category.

More than a third (34.8 percent) earned less than RM2,000 as of March. Therefore it’s clear that policy interventions should be comprehensive by ensuring the PWM considers the income distribution across different sectors and income groups that have struggled with the rising living costs post-pandemic.

The voluntary nature of the PWM could lead to limited participation and impact, as employers might prioritise short-term profits over long-term benefits.

However, if a large number of firms in a sector adopt the PWM, it could raise the general wage level, potentially leading to free-riding behaviour by firms that opt-out.

Voluntary or mandatory

Mandating the PWM could ensure uniform wage standards, reducing wage disparities and improving income distribution.

However, it could also increase labour costs, particularly for small and medium-sized enterprises, and potentially lead to growth in the informal economy as firms seek to circumvent these costs.

Therefore, the decision between a voluntary or mandatory PWM involves a trade-off between flexibility and equity, and must consider the potential impacts on different sectors and firm sizes.

The government’s plan to provide cash incentives for firms adopting the PWM could encourage participation, but if adoption remains low, there’s a possibility of the government considering a longer-term incentive approach.

This could contradict efforts to cut subsidies and improve fiscal position. The government should consider direct costs, indirect costs, and revenue effects when evaluating this approach.

The PWM is expected to be productivity-linked, similar to the existing Productivity Linked Wage System (PLWS), which has been adopted by 94,014 companies as of June 2022.

The PLWS, which links wages to company or employee performance, could work in tandem with the PWM. However, clear guidelines on productivity measurement are needed due to its subjective nature. The final form of the PWM, whether it complements or replaces the PLWS, remains to be seen.

Effects on bottom line

The implementation of the progressive wage model is poised to significantly impact businesses, potentially affecting their bottom line in various ways.

Firstly, there might be increased labour costs due to consistent salary increments and a more balanced wage distribution. However, this could be balanced by enhanced productivity resulting from the policy's focus on correlating income with performance, motivating workers to be more efficient.

Additionally, the policy's emphasis on higher wages could enhance employee retention, leading to long-term indirect cost savings through reduced turnover.

If not addressed, overlooking these aspects during the policy's rollout may leave businesses grappling with unexpected cost escalations and missed opportunities for productivity and retention benefits.

Foreign labour

Will the PWM apply to foreign workers? As of 2022, there were around 2.2 million documented migrant workers in Malaysia. These workers contribute significantly to various sectors of the economy, including manufacturing, construction, agriculture, plantation, and services.

Including them in the Progressive Wage Policy could ensure they are adequately compensated for their contributions.

However, higher wages and a clear progression for foreign workers could indirectly reduce job opportunities for local workers, impacting our citizens’ employment situation as employers might prefer hiring foreign workers if they can offer the same skills at the same wage level as they have generally always offered cheaper labour.

Additionally, the potentially large number of undocumented migrants could bring about regulatory challenges when enforcing the policy.

Unofficial estimates of undocumented or irregular migrants range from 1.2 to 3.5 million, making Malaysia one of the largest migrant-receiving countries in Southeast Asia.

The decision to include foreign workers in the Progressive Wage Policy must warrant a detailed and careful approach due to the significant role they play in the lower-skilled sector.

Subsidy mechanism

The government’s initiative to implement the PWM is laudable and should be supported, but there are some important issues and aspects that need to be considered and ironed out beforehand.

Firstly, a valid and crucial question has been asked on the budgeting of this proposed policy since its inception, but the answer to it has remained elusive about the subsidy mechanism proposed in the PWM, not even the parliamentarians could get the answer they were hoping for.

We hope the government will offer more clarity in this matter during the tabling of the White Paper.

It was publicly mentioned that certain sectors would be the focus under the PWM, but the bigger question is what would happen to low-skilled jobs or sectors that are mainly concentrated in city outskirts or rural areas? They equally need the attention and help under the PWM to improve their salary structures.

The voluntary nature of the PWM, which apparently is the central or main feature of this initiative, is controversial but also crucial as it holds the key to its implementation and success.

More questions could be raised if the company opts out of it for whatever reasons and it may in turn put their workers into an unfair situation compared to peers in the same job cluster or sector.

Furthermore, the PWM does not deal with the root cause of low-skilled workers; its large presence and continuous supply of low and unskilled labour would result in low productivity and depress the market wage for the very group of workers the government has aspired to help from the first place.

Weak unions, stagnant careers

The government also may have to consider the low unionisation rate in Malaysia and the absence of a strong tripartism tradition, which is one of the main requisites for the success and sustainability of the PWM.

This could become a drawback administratively as it involves intensive consultation and negotiations as well as interventions, rendering the improvements too slow and limited, failing public expectations. Not to mention, there is also concern about malpractices or corruption along its implementation.

A more delicate question also arises on whether the PWM would encourage worker’s mobility in a particular job or sector. Since workers may choose to stay within the same job or sector with a charted pathway under the PWM, how would it affect the job market, either positively or negatively?

Some quarters also wonder whether the PWM would be able to cover informal workers or foreign workers in Malaysia and how it could help part-time workers or flexi workers, as it appears to be more bureaucratically complex and costly.

Lastly, there is genuine concern that employers would become more likely to rely on subsidies and payouts given by the government under the PWM, rather than actually reworking or improving their business model to accommodate the proposed higher wage structures.

We hope these questions and situations will be carefully considered and answered by the government in the upcoming tabling of the White Paper.

Embracing change

In the end, the PWM, proposed by Rafizi, has sparked both hope and scepticism among Malaysians. The model aims to address the country's pressing economic issues, such as high unemployment, low wages, and a reliance on foreign workers.

However, its success depends on the willingness of employers, workers, and the government to embrace change and work together.

The White Paper should place emphasis on stimulating job creation by encouraging employers to invest in research and development, adopt new technologies, and create high-value positions.

However, the current economic climate, characterised by high unemployment and risk-averse businesses, raises concerns about the widespread adoption of these measures.

Another challenge lies in empowering fresh graduates and addressing underemployment. The PWM must provide clear career pathways and incentives for continuous learning and these measures are dependent on the quality of implementation and the active participation of both graduates and employers.

Combating brain drain and reducing reliance on low-wage and low-skilled foreign workers are also crucial aspects that should be addressed in the PWM.

Offering competitive wages and career progression opportunities is essential, but it may not be enough to entice skilled Malaysians to stay in the country when faced with better opportunities abroad.

Additionally, incentivising employers to upskill their local workforce may prove challenging in industries that rely heavily on foreign labour.

While the PWM holds promise in addressing Malaysia's economic challenges, its effectiveness hinges on the collective commitment and concerted efforts of all stakeholders, including employers, workers, and policymakers.

The model's success demands a harmonious blend of innovation, productivity growth, and lifelong learning.

In a nutshell, it is essential to carefully balance the need for fair wages with the potential economic and regulatory implications. Engaging all stakeholders in discussions is crucial to ensure a comprehensive and inclusive approach that reflects the diverse perspectives of all parties involved.

Only through unwavering dedication and effective implementation can the PWM propel Malaysia towards a more prosperous and equitable economic landscape. - Mkini

EDWIN OH CHUN KIT is a researcher at think tank Institute of Strategic Analysis and Policy Research (Insap).

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of MMKtT.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.