Throughout GE15, the mantra of both BN and PN has been stability, as they call on their voters to support them.

As the campaign reaches the final hours, it is worth reflecting on stability, the sources of instability in Malaysia and, importantly, what will strengthen the country as it moves forward.

Umno/BN: Lacking stability

Sadly, refusing to reform itself, and putting a leader (Ahmad Zahid Hamidi) tainted with corruption charges as its de facto prime ministerial candidate, Umno/BN has done the coalition no favours in this election.

Instead of rebranding, as it tried to do in Malacca and Johor with elected success (led in that effort by the currently side-lined Mohamad Hasan), the party has relied on its traditional base of support in the campaign, concentrated among older voters, and funded by its business allies, who believe that investing in the party will protect their financial interests.

Umno cannot get away from the fact that it has significantly contributed to political instability in Malaysia in the last decade.

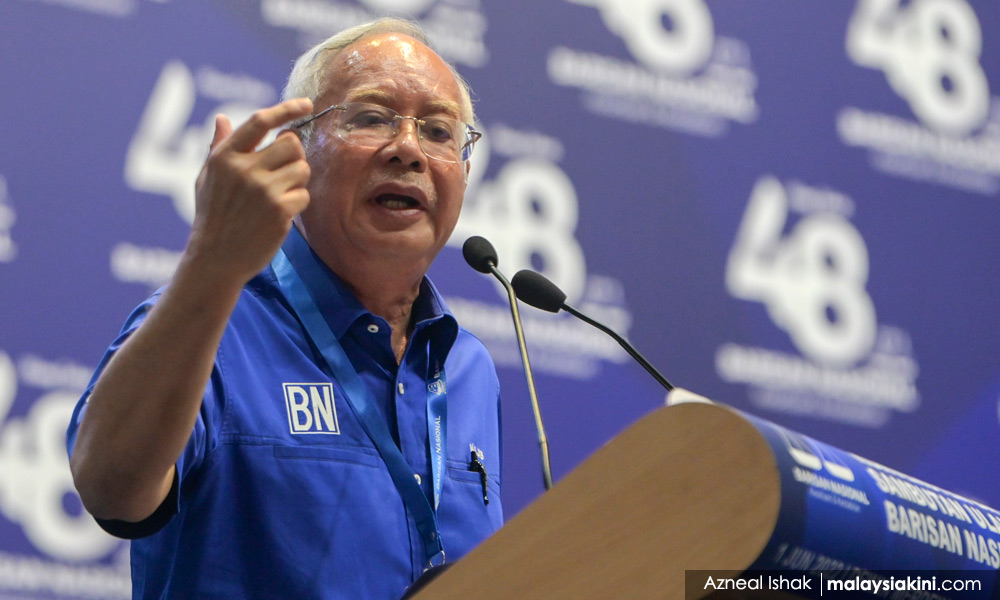

Former premier Najib Abdul Razak’s greed in the 1MDB scandal split the party and negatively impacted the country’s reputation. 1MDB contributed to Umno being ousted from power in the last election.

Rather than reform through party polls in 2018, corrupt practices and hierarchical feudal culture kept incumbents in power, where for the past few years, they have (not surprisingly) focused their efforts on protecting the elites of the party. These personal priorities of legal cases and removing charges/pardons were made clear at the onset of the GE15 campaign.

Umno adopted a range of tactics to return to power after its electoral defeat in 2018, from first forming the Muafakat Nasional alliance with PAS to heightening racialised politics.

At the same time, Umno/BN fostered ‘deep state’ resistance to policies inside the system, opposing political reforms. For months, Umno/BN worked to create a narrative that further polarised the electorate along racial lines.

Leaders such as Najib who resigned initially, returned back to positions of power and were profiled by the party, further stymying the rise of younger leaders and needed new leadership in Umno.

History will debate the architects of the 2020 Sheraton Move for decades to come. Few questioned that Umno was involved and benefited as it returned them to power.

When it proved dissatisfied with being in a coalition as a partner rather than fully in charge, it pressured Muhyiddin Yassin’s government initially for more/higher positions and later for his resignation. While here too many decisions were made by different individuals, again, Umno was a pivotal player that led to the change of government in August 2021.

Although from Umno, Ismail Sabri Yaakob who assumed power was never given the space to set his own leadership. It was Pakatan Harapan’s memorandum of understanding that served to stabilise his leadership.

Ismail Sabri failed to take the time to clean up Umno. Yet, he faced relentless pressure and ultimately gave in by calling the early GE15 polls. He faces a battle to reassert his leadership after GE15.

Umno’s internal divisions have been on display this campaign, and these differences will continue to contribute to political uncertainty. Until Umno has new leadership, meaningful rebranding and moves forward, it is locked in a destabilising role.

The old adage that problems in UMNO are Malaysian problems remains relevant.

Re-polarisation by PN

If Umno’s internal issues have reverberated nationally, it is Perikatan Nasional’s tactics in this GE15 campaign that will leave scars.

In the last week of the campaign, PN, cloaked in similar conservative BN blue, unveiled an ugliness in hurtful remarks about non-Malays/Muslims.

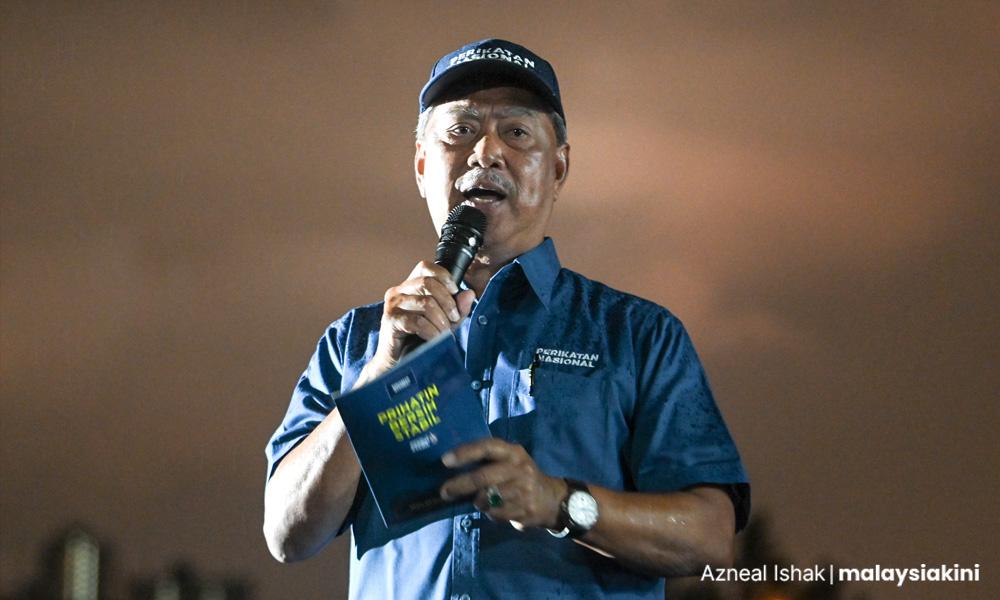

Some may think these are so frequent that they are par for the course in Malaysian politics. Yet two red lines were crossed – one was a call for violence at a party state government-funded event and another was remarks uttered by a prime minister candidate, a man who is supposed to represent all Malaysians.

Usually, these types of remarks are used to rise within parties, or in quiet engagement rather than in public speeches. That the very public remarks used disinformation to feed conspiracies as well as were divisive is especially worrying for a national leader.

Malaysia remains scarred from its racialised politics. The scars run deep across communities. The mobilisation of race and religion divides and feeds sentiments of fear, displacement and anger – long emotions in campaigns that all sides have used to various degrees. This last emotional PN swing will shape voting.

The irony of these sets of remarks is that during Muhyiddin’s PM leadership in 2020-2021, his lack of strong political support forced him to reach out, to be more inclusive.

Sadly, he has abandoned this more inclusive approach in the PN GE15 campaign. A situation where Malaysia is polarised, and divided does not shore up national stability.

Concretising promises

On its part, Harapan is fighting to win seats. Unlike in the past with Mahathir at the helm, it now has more of a shared reformasi outlook in the coalition. While personality differences are there and some egos are over-inflated, there is common ground and less open party/coalition conflict compared to 2018.

The coalition wrestles with three issues for stability. The first is winning Malay support. It needs to secure a core share of Malay votes, which have increased as the campaign has progressed. The question will be whether rural and semi-rural areas also support the coalition.

An obsession with the issue of Malay support undercut Harapan 1.0, as it was Mahathir’s myopic focus. The issue now is to be confident with a limited base of support that provides ground to work from and programmes/communication that addresses the challenges faced by the Malay community, including those in Felda/Felcra areas too long neglected.

A key Mahathir failure in Harapan 1.0 was his austerity in the social safety net, which eroded support garnered in GE14. At this current time of vulnerability, new programmes are needed for all communities that strengthen the social fabric. It is only through actual programmes to resolve divisions that the impact of the rhetoric of displacement can be reduced.

Another dimension of stability involves proper respect for Borneo. Stability comes from recognising meaningful measures to address long-standing inequalities and neglect.

Harapan’s manifesto has the most measures of all the coalitions in this regard, but promises need to be concretised, as mindsets also need to evolve. Borneo is not just to borrow support (to get the numbers); it is to deliver the support needed.

A third challenge is to showcase the confidence that it can manage the economy, especially the business community. Ultimately, stability in Malaysia comes from economic management. All three coalitions vary little on actual policies and approaches to the economy.

Harapan 1.0 undercut itself with a focus on stopping projects, a perceived vengefulness, and undercutting funds into the economy. This sort of approach was destructive and until now, resentment resonates among some voters who felt their areas were ‘punished’.

An ‘us versus them’ opposition mentality of the past will not be the right approach to strengthen Malaysia as it faces strong negative global recessionary headwinds ahead.

So far, the Harapan campaign – at least from its manifesto and campaign – has shown it has learned from its experience in government and the punishment from voters in two state polls. Whether it keeps learning will be important ahead.

Rocking Malaysians

From internal coalition cohesion, identity politics, inclusion and management of the economy, the sources of instability are present. Campaigns can promise but it is delivery that will matter.

Yet, the last few years have shown that Malaysia is strong despite the changes in government and that its people survived in spite of its politicians. (Much) more can be done to make them thrive and survive better.

Nevertheless, the foundation of stability in Malaysia comes from its people, the deep devotion that Malaysians have for their country, from all walks of life. The dreams of a stronger country are checking the excesses of those in power, and reinforcing what I expect will be the highest turnout in history in any election in terms of overall numbers of voters.

No country in the world (to my knowledge) has so much commitment to vote, from overseas ballots being amazingly organised to the long (and expensive) trips home.

While nostalgia has been important in some coalition campaigns, the main driver underscoring this election remains a focus on a better future – one which Malaysians are working to achieve.

The GE15 campaign has reaffirmed citizen empowerment, voters willing to change political loyalties reflect on their political choices, and they will go to the polling station after one of the most testing times in national history.

Whatever happens tomorrow, ordinary Malaysians are the rock protecting their future. - Mkini

BRIDGET WELSH is an honorary research associate of the University of Nottingham, Malaysia’s Asia Research Institute (Unari). She is also a senior research associate at the Hu Fu Centre for East Asia Democratic Studies and a senior associate fellow of The Habibie Centre. Her writings can be found at bridgetwelsh.com. Check out her Kerusi Panas podcast series.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of MMKtT.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.