In 1998, the then-Umno Youth chief, Ahmad Zahid Hamidi claimed that nepotism and cronyism were practised in awarding some privatised projects.

Immediately, then-premier Dr Mahathir Mohamad released the list of people awarded privatised projects.

“There are literally hundreds of them, and quite obviously, they are not cronies of us (Mahathir and his deputy, Anwar Ibrahim),” he said.

This was more restricted information than a breach of the Official Secrets Act, as details of these companies’ beneficiaries could be discovered through searches at the Companies Commission of Malaysia.

Three days after Parliament was dissolved on Oct 10, 2022, then-caretaker prime minister Ismail Sabri Yaakob admitted that he had declassified the report detailing Putrajaya’s investigation into former attorney-general Tommy Thomas’ book so that it could be used as political “bullets” to attack Pakatan Harapan.

“I have given you bullets. In Thomas’ case, we exposed (the report) by the special task force. I have given lots of bullets here.

“I asked the de facto law minister to publish it on their website, to detail what was done and what mistakes Thomas made.”

The process involving declassifying government documents is simple and not protracted, especially when it is done for political expediency.

However, in other circumstances, the civil service and its officers must be severely scrutinised for their competency, efficiency, and urgency.

The methodology is simple. The requisitioner writes to the ministry’s secretary-general or a government agency’s director-general detailing the documents that must be declassified and stating specific reasons for the request.

Then, he or she will initiate a letter to the respective minister citing the request, after which a working paper will be prepared for cabinet approval.

Najib and Irwan’s DNAA

Usually, the cabinet rubber stamps the approval, mainly when such documents are used to prosecute alleged wrongdoers.

Therefore, one must agree that the Attorney-General’s Chambers had no control over the documents that needed to be declassified for the trial of former prime minister Najib Abdul Razak and former Treasury secretary-general Mohd Irwan Serigar Abdullah.

Both were charged with criminal breach of trust (CBT) involving RM6.6 billion in alleged payments to the Abu Dhabi government’s International Petroleum Investment Company (IPIC).

Both were granted a discharge not amounting to an acquittal by the High Court last week after the prosecution admitted it had failed to hand over related documents to the defence.

It has become a practice for the AGC to maintain stoic silence when asked to comment on an issue or being criticised for its actions or inaction.

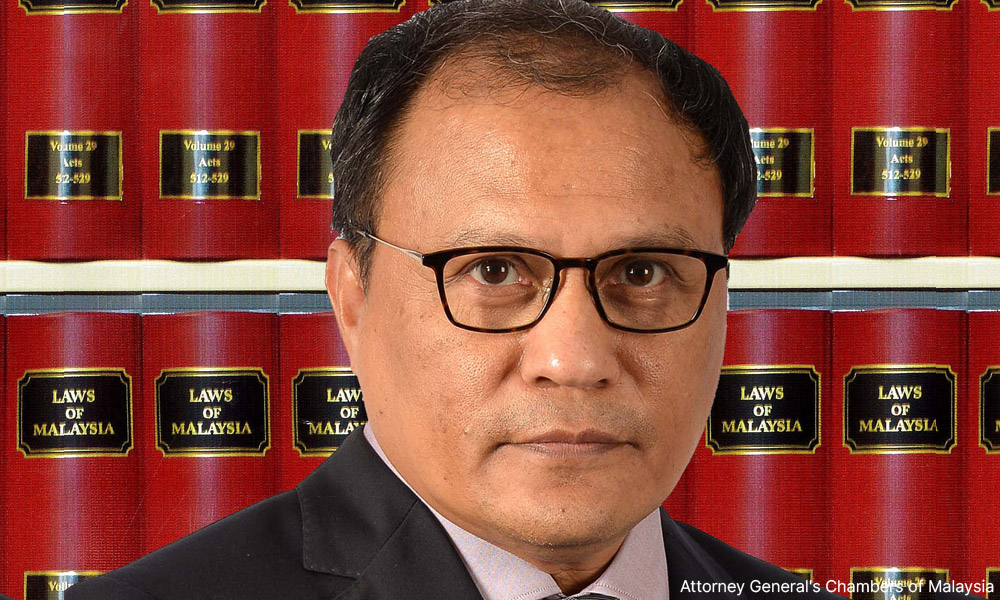

When the AGC applied for DNAA in Zahid’s case last September after his defence was called, then-attorney general Idrus Harun did not explain the decision.

Instead, it was Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim who came to the fore, speaking on his behalf.

He said the charges were so flawed that they bothered Idrus’ conscience, who wanted to set things right before he left office.

Anwar, who previously denied interfering in the decision as it was within the powers of the AG, said that the charges against Zahid were “questionable” and not carried out professionally.

“Was it 47? Every cheque is a charge. So, the charge is questionable. Every cheque issued is a charge by itself, which does not necessarily seem to be professionally done,” he said when asked about the dropped graft charges during a session at the annual Milken Institute Asia Summit in Singapore.

But Anwar failed to explain that the law requires every cheque to form a separate charge.

Anwar also repeated Zahid’s claim that charges had been brought against him in 2019 because he refused to fulfil then-prime minister Mahathir’s demand to dissolve Umno.

What went wrong?

So, in the case of Najib and Irwan, what went wrong, and who was responsible?

The documents are from the Finance Ministry (which included the Minister of Finance Incorporated), the Energy and Water Transition and Transformation Ministry, and the Transport Ministry (which involved the Land Public Transport Agency, previously known as the Land Public Transport Commission, which falls under the Road Transport Department).

So, the questions are: Did the AGC submit the request to declassify the documents from these ministries after the duo was charged on Oct 24, 2018?

Were these requests ever tabled for the cabinet to approve?

While using Thomas as a punching bag has become savvy, what about his successors?

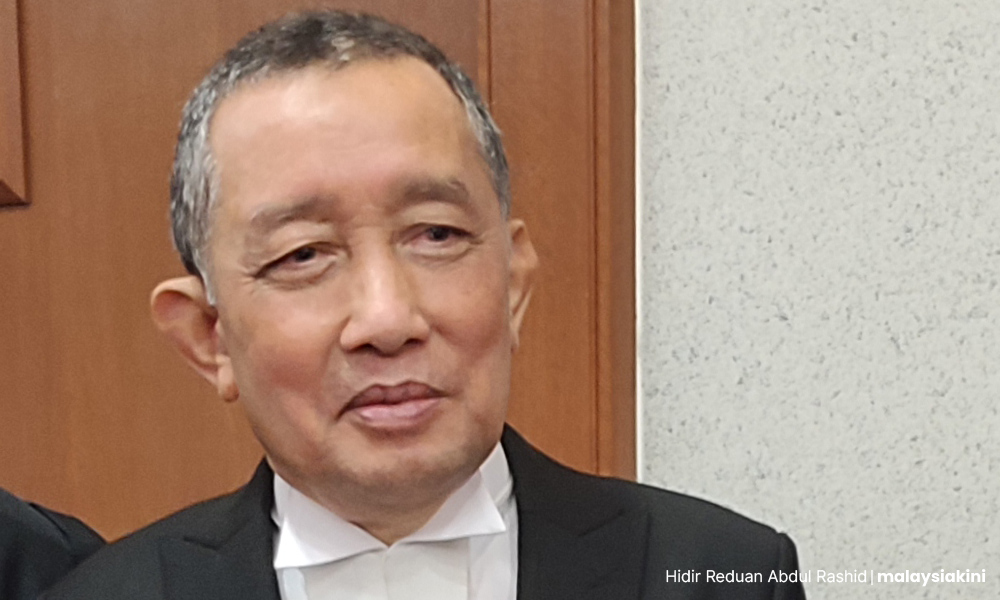

Since March 1, 2020, there have been four attorneys-general – Engku Nor Faizah Engku Atek, Idrus, Ahmad Terrirudin Mohd Salleh, and now, Mohd Dusuki Mokhtar.

Which of these ministries acknowledged receipt of the request or responded? Were reminders sent? Or did they ignore the requests?

Shouldn’t the buck stop with the finance minister, who has been shouting himself hoarse for the past two years to compliment his fight against corruption?

What about the chief secretary to the government? Isn’t this a damning condemnation of senior civil servants? Isn’t this a classic case of “they cannot even organise a drink-up in the brewery?

Or is it a show of the much-talked-about deep state within the system?

Unless the AGC speaks up and points the finger at the erring parties, can we assume that one or more parties had orchestrated the delay? - Mkini

R NADESWARAN is a veteran journalist who writes on bread-and-butter issues. Comments: citizen.nades22@gmail.com

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of MMKtT

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.