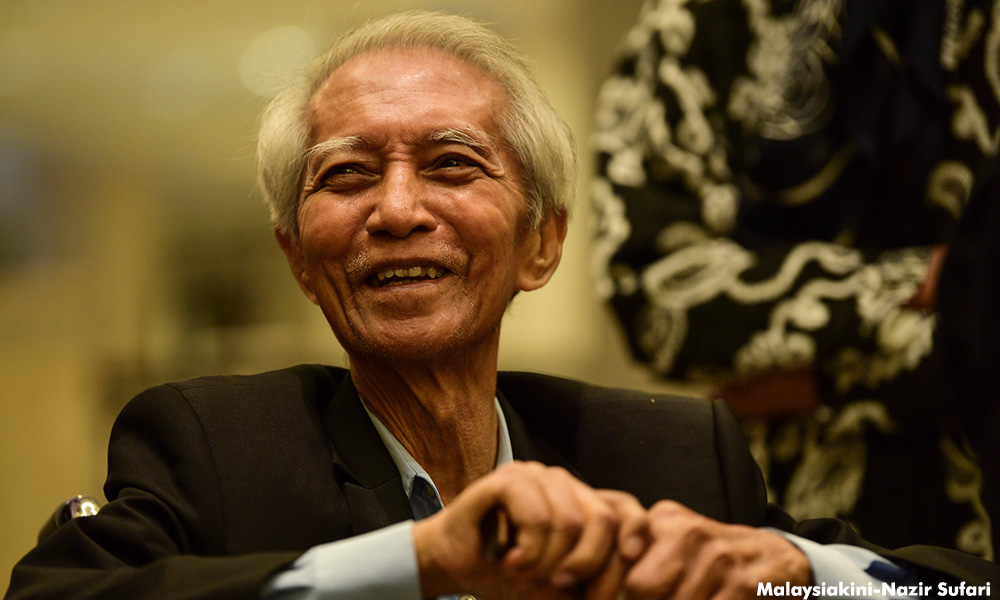

For Kassim Ahmad, a discourse has no winners or losers, only people interested in discovering their faith.

“According to government data, the objectives of the NEP have yet to be achieved. But I think the Malays have this consensus… these special privileges that have made them comfortable. They have this comfort zone where they face no challenges. Because of this, they don’t see the necessity in putting in the effort to progress. So they are weak and lack competitiveness. It is better to end something that does no good to the people anymore.”

– Kassim Ahmad

There is this meme as to the kind of Muslim the late Kassim Ahmad was. To his admirers, the persecution of this public intellectual demonstrated the fear the state had to what he wrote and said, and this made him the poster child for the kind of Islam they believed was “acceptable” in a multiracial and multi-religious country like Malaysia.

To his detractors, he was a purveyor of falsity that threatened Muslim solidarity and he was a puppet of the “opposition” whose writings and speeches would cause the collapse of Malay/Muslim political and religious hegemony.

Indeed, some opposition supporters would be perplexed of some of the things he said about certain opposition politicians and the Umno state would be perplexed at some of the positions he advocated after they had branded him a deviant and an “enemy” of Islam.

The truth was that Kassim Ahmad was a devout Muslim who believed that his faith was hijacked by interpreters who had agendas of their own that were not compatible with his own interpretation of what would lead to a liberated world.

He had many young followers of his work who often told me that what was inspiring of his interpretation of Islam was that it did not foster fear but hope and that through questioning of what they were told and taught, they would be liberated from the falsities that were all around them.

He encouraged dissent, especially on his own writings, and he was cognisant that ultimately this was a discourse that had no winners or losers, only people who were interested in discovering their faith.

Unfortunately for him, the world is a cruel place. Those who make the claim that theirs is really a religion of peace do not have the empirical evidence to support such a claim. Indeed, the persecution of Kassim Ahmad was evidence that thinking was verboten.

The duplicity, arrogance, and illegality of the Federal Territory Islamic Religious Department (Jawi) in its persecution of this religious scholar is a matter of public record. Indeed, not only was Kassim Ahmad targeted but also his long-time advocate Rosli Dahlan.

There were things he said and wrote about that a person could disagree with. Depending on your own belief system, they were roads that Kassim Ahmad walked that you would have no desire to travel on but what separates Kassim Ahmad from the petty religious bigots that persecuted him was that he would never dream of imposing his beliefs on others.

Indeed, he welcomed discourse. He welcomed the challenges his ideas inspired. He wanted Muslims to think about their religion, but more importantly, think for themselves. His was a quiet revolution of the Muslim soul.

Blind faith

This is an example of what baffled him – “Malaysia happens to be a strong upholder of hadith(s). Sometimes the so-called experts, appearing on the Forum Perdana every Thursday night, quote the hadiths more than the Quran.

“Muslim scholars, Bukhari and five others, collected many thousands of so-called hadiths and classified them as authentic or weak 250 to 300 years after the death of Prophet Muhammad. These are collections of the Sunni sect. The Syiah have their own collections of so-called hadiths.

“To my mind, these fabricated hadiths are a major source of confusion and downfall of Islam.”

If ideology and religion is the lens through which some view the world, it is understandable (for those who know anything about Islam) as to why someone like Kassim Ahmad would find succour in this religion which has been weaponised here in Malaysia and the rest of the world. A religion he thought – which is different from “believed” because he put in a great deal of effort and time into “thinking” about his religion – could be a salvation to the problems of the world.

Here is another snippet in his own words - “In the University of Malaya in Singapore, I joined the leftist Socialist Club and later joined the People’s Party of Ahmad Boestamam, and quickly became its leader for 18 years! Somehow or other, I did not feel real about the power and success of socialism. It was simply to identify myself with the poor to whom I belong.

“I was therefore critical of things I inherited from my ancestors. The first scholar I criticised was Imam Shafi’e for his two principal sources (Quran and Hadis). The book ‘Hadis - Satu Peniliai Semula’ in 1986 became the topic of discussion for two months, half opposed and half supporting me. After two months, it was banned.”

Anyone who has read what this scholar believed his religion was about, would understand that Kassim Ahmad’s sympathies for the marginalised were paramount in his belief structure. You could make the argument that his beliefs gave structure to what he eventually hoped rational Islam could accomplish.

Having the mindset of being critical of what you inherited from your ancestors is the most potent tool an adversary of state-sponsored repression could have. This was why they feared this quiet scholar who simply spoke of things that his interpretation of his religion inspired in him.

His intellectual contribution to Islam was anathema to people who believed that blind faith was true faith and his steadfastness in not disavowing what he said, his noncompliance to the diktats of the state was a wound that would not heal for those who wish to impose their beliefs on others.

When I read of how the state persecuted him, I understand why he posed such a threat. If Muslims realised that their interpretation mattered then the so-called scholars would lose their influence and their hegemony of the debate would vanish. Kassim Ahmad was a constant reminder of what would happen if people embraced a religion that they had thought out for themselves.

In a time when the Islamic world is suffering from a dearth of outlier voices, the passing of Kassim Ahmad is a great loss not only to Malaysians but to the other sparks in the Muslims world waiting to be ignited by people who choose not to subscribe to fear but who genuinely want to understand their religion.

I will end with this quote by Henry David Thoreau. Hopefully, it means something –

“On the death of a friend, we should consider that the fates through confidence have devolved on us the task of a double living, that we have henceforth to fulfil the promise of our friend's life also, in our own, to the world."

S THAYAPARAN is Commander (Rtd) of the Royal Malaysian Navy.- Mkini

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.