Jawi has been the main script of the Malay language in the Malay Peninsula and the Malay Archipelago for hundreds of years before the coming of the British. It replaced the old Malay writings of ‘Rencong’, ‘Pallava’ and ‘Kawi’ that was used widely within the Archipelago during the heyday of the Malay Kingdom of Srivijaya in the seventh century AD.

When Islam was embraced by the majority of the Malays, Jawi script was introduced and is evident in the Kuala Berang Inscription of 1303 as well as in the Laws of Malacca and Maritime Laws of Malacca narrated in the fifteenth century AD.

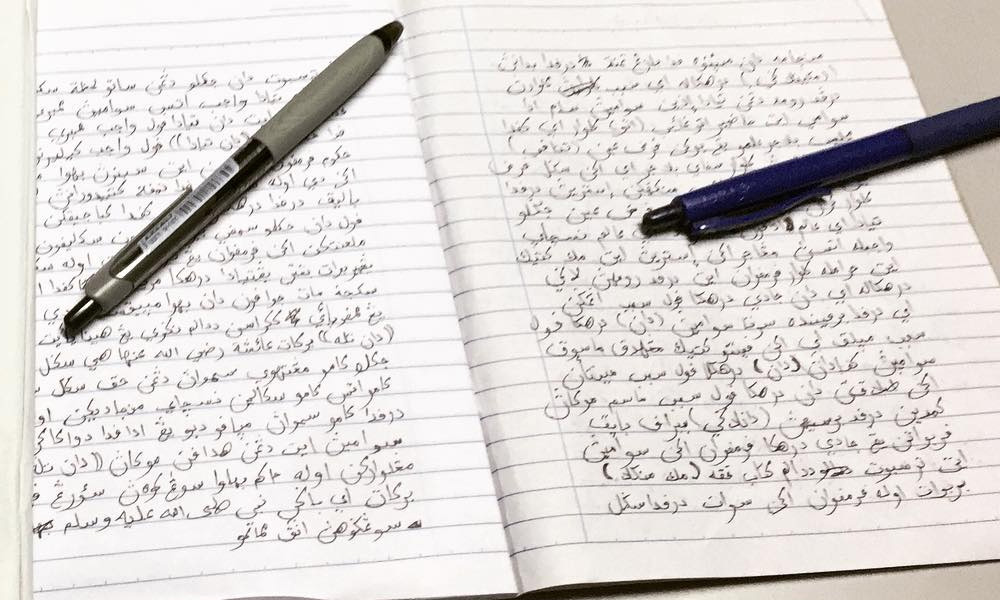

Jawi is not a language, but the Malay alphabet modified from Arabic script, like that of Persian and Urdu scripts.

Malay is the national language of not only Malaysia, but also Brunei, Singapore and Indonesia (as Bahasa Indonesia). It has been used as the lingua franca and the main medium of instruction for knowledge and trade as well as international communications within the archipelago for centuries. This was made possible through the application of the Jawi writings.

The Dutch and the British communicated through Jawi scripts to reach out to sultanates of Johor, Aceh, Banten, Pontianak, Mindanao, Brunei and other kingdoms sprawling all across the Archipelago during colonial times.

It remains now as one of the symbols of the nation engraved in the national and state emblems and ringgit notes, among others. It was also used in the Declaration of Independence signed by our Father of Independence, Tunku Abdul Rahman in 1957.

Recently, ‘Khat Jawi’ was planned to be inserted as one of the topics in Year Four Bahasa Melayu subject. However, this was strongly opposed mainly by Chinese associations like Dong Zong and Jiao Zong, citing ‘Islamisation’.

Prime Minister Tun Dr. Mahathir lashed out at these associations claiming that they were ‘racist’ and ‘disliked the Malays’.

It is indisputable that the members of Dong Zong and Jiao Zong regard themselves as Malaysians. However, if they really are Malaysians at heart, don’t they realise that they are in fact insulting the sanctity of one of the symbols of the nation?

When Malaya was made part of the British Empire in the nineteenth century, the British brought in Chinese and Indian immigrants to toil British-owned mines and plantations scattered all over Malay Peninsula.

The non-Malay communities in Malaya at that time, particularly the Chinese and Indians realised that citizenship rights were crucial for the interests of their communities. Upon independence, these immigrants were accorded citizenship rights as long as they respect the special rights of the Malays, Malay as the national language of the independent Malaya, Islam as the religion of the Federation and the acknowledgement of the sovereignty of the Malay rulers, all of which are embedded in the Federal Constitution.

While the Rohingyas in Myanmar were denied citizenship rights, the Chinese were not accepted in Vietnam and Cambodia, and the Tamils in Sri Lanka were sidelined by the Sinhalese, millions of non-Malay immigrants were granted citizenship rights of the newly formed sovereign State of Malaya in 1957.

This gracious acceptance of the Malays towards the non-Malays was acknowledged by the then President of the Malayan Indian Congress (MIC), Tun VT Sambanthan in 1965 and the late Tun Tan Siew Sin, the third President of the Malaysian Chinese Association (MCA) in 1969.

Unlike Thailand and Indonesia that banned the usage of languages other than Thai (through the thesapiban system) and Bahasa Indonesia (through Suharto’s New Order) respectively, Malaysia adopted a different method by allowing minority groups to practice and preserve both their ancestral language and culture. Nevertheless, Malaysians should always realise that the national language of this country is Malay.

Malay is made the national language of Malaysia as prescribed by Article 152(1) of the Federal Constitution. Contrary to popular belief, the term used in the Federal Constitution is not ‘Bahasa Malaysia’ but ‘Malay’. Section 9 of the National Language Act 1963/67 mentioned clearly that the official script for the Malay language is Rumi with the condition that the usage of Jawi is not prohibited.

It is very shameful that there are Malaysians born and bred in this country not being able to converse well in the national language. There are Malaysians who got agitated when they are labelled as ‘pendatang’ or ‘immigrants’. However, this stigma would not go away unless all Malaysians improve their mastery of the Malay language.

How could one differentiate themselves with a Chinese, Indian or British national if one could not uphold the national language? If Bangladeshis and Nepalese migrant workers could learn to speak Malay, why would it be difficult for Malaysians themselves to learn and speak it properly?

Now, the Jawi script, which is part of the cultural heritage of the Malay language, is being ridiculed by those who consider themselves Malaysians.

There are unwarranted arrogant comments in social media stating that the Malay language is useless and the Jawi script has no market value. According to Foreign Tongues, the market research translation agency based in the United Kingdom, Malay is in fact, the sixth most-spoken language in the world with 281 million speakers.

Jawi on the other hand is upheld and preserved by our neighbouring country, Brunei Darussalam, one of the richest nations on Earth.

Education is not just about training students to find jobs, but also to teach them self-belonging as well. How could one inculcate love towards the national language without learning the origins and importance of the language itself?

Brunei has been successful in inculcating this in the minds of its people. If Brunei could do it, why can’t us, Malaysians?

Malay is the nation’s language, a symbol of pride and unity of all Malaysians. Jawi script is a national heritage that is supposed to be respected by all. Prime Minister Tun Dr. Mahathir Mohamad is right in reiterating the importance of learning ‘khat Jawi’ for all Year Four students.

It's time for all Malaysians, particularly members of Dong Zong and Jiao Zong, to emulate the spirit of ‘I’m Malaysian, not Chinese’ expressed by the Finance Minister Lim Guan Eng on May 12, 2018.

As Malaysians, let us respect the sanctity of the national language and the Jawi script - both protected by the Federal Constitution and the National Language Act 1963/67.

MOHD HAZMI MOHD RUSLI is a lecturer at the Faculty of Syariah and Law, Universiti Sains Islam Malaysia. He is also a visiting professor at the School of Law, Far Eastern Federal University, Vladivostok, Russia. - Mkini

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.