I am in full support of khat being taught as part of Malay language education in national schools.

Before I began my undergraduate studies, I decided to enrol in a one-day introductory workshop on the Jawi script, its history and romanisation of the Malay language.

I recall the wide-eyed amazement of the facilitators, who were young Islamic studies scholars.

“It’s rare for non-Malays to come by our centre these days unless they are researchers from abroad. We are happy that you have decided to join us today,” one of them warmly said.

For me, it was always very fascinating to find out more about the overlap between the Malay and Arab worlds because of its rich intellectual and cultural diaspora.

My interest in Jawi started developing since my schooling days. This was because I realised that many prominent Malay intellectuals, dating back to as far as the 13th century, wrote their contemplations in Jawi.

Yet, this indigenous philosophical tradition had been rendered quite invisible in our everyday conversations about Malaysian intellectual history.

It was from this workshop that I learnt various scholars have concurred that Jawi writing is a product of the legacy of Islam and the Arabic language spreading across the Malay Archipelago.

The inability to separate Islam from Jawi stems from a commonly held notion that Arabic remains superior to other forms of language in the region due to its status as the language of the Quran.

The most popular held notion about the origins of the Jawi script is the one propounded by the venerated Islamic philosopher, Syed Muhammad Naquib Al-Attas.

According to him, Jawi was directly derived from Arabic, introduced by Arab missionaries of Hadrami origin without any intermediaries such as Persians and Indians.

It was from this moment on, I found myself determined to learn more about Malaysia’s past through Jawi manuscripts. During my second year in university, I enrolled in a module titled 'Understanding the Malay World', taught by my mentor, Sumit Mandal.

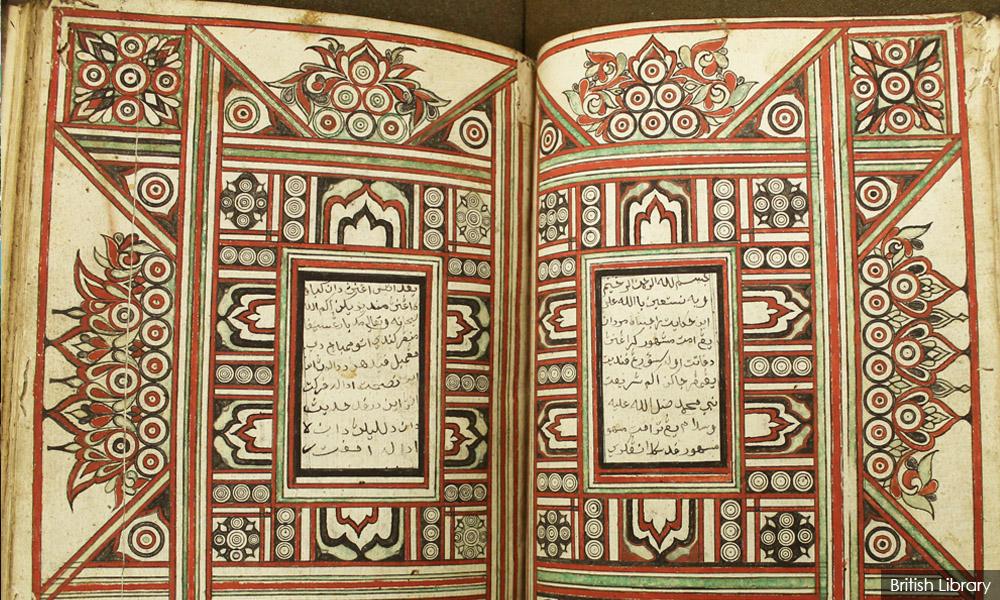

Eager for me to practice my newly acquired reading skills and knowledge of Jawi, he encouraged me to undertake a research project on a Malay manuscript of my choice. I selected the title Hikayat Syah Mardan.

The purpose of my study of this text was to explore intercultural connections that go beyond the modern-day borders of Malaysia and Indonesia.

As I furthered my study of this 17th-century Malay manuscript, it dawned on me that the understanding of the Jawi script and its origins I was previously taught was not set in stone.

In fact, there is a vast amount of literature that continues to challenge the exclusive 'Islamic' nature of literature written in Jawi.

Through a detailed analysis of Hikayat Syah Mardan, I discovered that it was quite difficult to pin down the tale’s origins to a single place.

Similar narratives and characters have been found in places like India and Indonesia, Thailand and Vietnam, making this manuscript a testament to more complex social dynamics taking place in the Malay world during this period.

An even more interesting discovery was that this hikayat demonstrates how Hindu-Buddhist motifs take centre stage in creating an effective narrative about its protagonist’s spiritual advancement.

This led me to conclude that pedagogical Islamic teachings that were being expressed in Malay society were dependent on older, persisting literary conventions that belonged to the Hindu-Buddhist history of our nation.

Without them, profound lessons of courage, humility, wisdom and love would have been lost in translation.

These findings forced me to reconsider the extent to which Malay manuscripts are exclusively framed within the conventions of the Arabic language, and monolithic Islamic ideals.

Was Hikayat Syah Mardan an anomaly in the vast array of Malay literature? Surprisingly, it isn’t!

Southeast Asian historian Ronit Ricci’s examination of The Book of One Thousand Questions revealed that notions such as “creeping Islamisation” or “Arabisation” do not truly capture the transformative process in religion and culture that took place in Southeast Asia.

Instead, she uses the word “Arabicised” to describe how Arabic influenced local languages by “combining with them rather than by replacing them.”

Ricci demonstrates this by showcasing variations of the book in Javanese (Serat Samud), Malay (Kitab Seribu Masalah) and Tamil (Ayira Macala).

Through her study, it became evident that the literary tradition of Southeast Asia was “richly interconnected both with a distant past and with a local present” in order to create and maintain a shared sense of identity between Muslims and non-Muslims alike.

Yet, it appears that such a conception of traditional Malay literature has become marginalised.

As pointed out by novelist Faisal Tehrani (photo) in a recent lecture, Islamic literature in the corpus of Malay language works are given greater prominence to the point they have become synonymous with national literature, relegating other genres, including more hybrid works to the side.

This has resulted in Malay literature being divorced from its equivocal origins in the past few decades.

With this in mind, the amount of negative feedback that the Education Ministry has received on this proposal over khat, or Jawi calligraphy, has been pretty... khat-astrophic.

If one were to take a glance at Facebook comments, many users write about how the Jawi script belongs to Arabic culture, rather than a Malaysian one.

A great deal of sentiment is rooted in the idea that this move is in tandem with the “creeping Islamisation” that continues to plague this country.

Even groups such as coalitions in support of Chinese independent schools, Dong Zong and Jia Zong, have voiced their dissatisfaction, and were reported to have mobilised Tamil schools to take a similar position.

It might be easier to dismiss the fear of khat to be as irrational as the fear of crosses. But in reality, there is a persisting historical context that informs the controversy that this issue has garnered.

The miseducation of khat is inherently a part of Malaysia’s colonial legacy of language management to bring order to our multilingual society.

In her book Taming Babel: Language in the Making of Malaysia, historian Rachel Leow highlights that the strategies employed by British administrators left a lasting impact on the social and political landscape of 20th century British Malaya.

As Bahasa Malaysia transitioned from Arabic to romanised script, the production of texts would also be shifted from manuscript to print form, for the ease of regulating the development of the language.

The same had occurred with Chinese languages, resulting in incessant tensions in Malaysia’s communal relations.

This would be further exacerbated by the “mentality of crisis” in postcolonial Malaysia, which wrangled with shaping Malay identity.

Evidently, these events led to the continuous absence of recognising the plurality of languages in Malaysia, underpinned by a deep resentment of a diverse society.

It is certain that a lot of work needs to be done by the government of the day to adequately address the shortcomings of Malaysia’s national education system, especially because it has cost us racial harmony.

But as a young Malaysian who loves learning about history, I would like to remain hopeful about how this move can inspire agency among a younger generation of Malaysians to dig deeper into our history without the need of a handful of historians and linguists.

In making 'Malaysia Baru', perhaps it is time to seek a sense of belonging that goes beyond what we have been told and ask ourselves - can we khat out all this fighting?

NETUSHA NAIDU is the co-founder of Imagined Malaysia, an NGO dedicated to the promotion of historical education among young Malaysians. She is currently pursuing her post-graduate studies in Southeast Asian history at St Catharine’s College, University of Cambridge. - Mkini

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.