HISTORY | The Portuguese Eurasian community in Malaysia, arguably “sons of the soil” with a heritage tracing back five centuries to Malacca, has become a forgotten part of the nation’s tapestry.

Their invaluable contributions to nation-building and Malaysia’s rich multicultural heritage are rarely acknowledged, receiving only fleeting mentions in today’s school history textbooks.

This neglect diminishes the legacy of a vibrant and resilient community - one that has blended cultures, stood the test of time, and helped shape the nation’s identity.

Origins of Portuguese Eurasians

The Portuguese Eurasians trace their origins to the early 16th century when the Portuguese captured Malacca in 1511.

Following the conquest, a small number of Portuguese soldiers, administrators and traders settled in Malacca, intermarrying or cohabiting with local Malay, Javanese and Batak women.

This union gave rise to a distinct Eurasian community that adopted elements of both Portuguese and local cultures.

Common surnames adopted by the Portuguese Eurasian community include Aeria, Almeida, Carvalho, De Costa, De Cruz, De Silva, De Souza, Gomes, Lazaroo, Lopez, Machado, De Mello, Monteiro, Nonis, Nunis, Oliveiro, Pereira, Pestana, Pinto, Rodrigues, Santa Maria, Sequerah, Skelchy, Theseira, Vaas and Xavier.

The Portuguese Eurasians also have Dutch and Anglo-Saxon ancestry, inherited through several generations of intermarriages.

According to Chan Kok Eng, in his article “The Eurasians of Melaka” (1983), Dutch Eurasians and other Eurasian sub-groups have been assimilated into the Portuguese Eurasian community and “are no longer distinguishable from Eurasians of Portuguese descent, except very tenuously by their surnames.” Common Dutch surnames among them include Cornelis, De Witt, Frederik, Goonting, Marbeck, Minjoot, Spykerman, Van Huizen, and Westerhout.

With the expansion of British rule in Malaya, the Eurasian population, particularly in large towns like Kuala Lumpur, Penang, and Seremban, grew with the arrival of the Portuguese and Dutch Burghers (Ceylonese Eurasians) who came at the beginning of the 20th century as medical doctors, surveyors, and government officials; and Anglo-Indians from India, who primarily worked as railway staff. Nevertheless, the Portuguese Eurasians predominated both in terms of numbers and cultural impact.

Settlements and occupations during Portuguese, Dutch, and British rule

Under the Portuguese administration (1511–1641), Portuguese Eurasians held key positions in trade, governance, and military service. Many were involved in commerce, shipbuilding, and administrative roles within the colonial government.

However, under Dutch rule in Malacca (1641–1824), apart from 1795–1818 when the British temporarily took control of Malacca due to the Napoleonic Wars in Europe, the Portuguese Eurasians faced discrimination and marginalisation. The Dutch, being Protestant, were less tolerant of the Catholic Portuguese Eurasians, leading to a decline in their influence.

Most of the land belonging to Portuguese Eurasians was seized and sold to Dutch officials and their descendants. Despite facing economic hardships, many continued working as fisherfolk, traders, and artisans. Others fled inland, while some sought refuge in Kedah and Phuket. According to a 1678 census, there were 1,469 Portuguese and their descendants from mixed marriages living in Malacca.

During British rule, the Portuguese Eurasians fared much better. The British authorities restored some of their land titles. They were considered as part of the colonial elite due to their European heritage and were granted privileges in education and employment. In 1871, there were about 2,000 Portuguese Eurasians in Malacca.

With the establishment of British settlements in Penang (1786) and Singapore (1819), the Malaccan Eurasian Portuguese began migrating to these locations.

In 1821, there were 12 Roman Catholics of Malacca-Portuguese descent in Singapore. By 1871, the Eurasian population had grown to 1,383 in Penang and 2,164 in Singapore, with a large majority being Portuguese Eurasians.

Towards the end of the 19th century, Malaccan Portuguese Eurasians, along with other Eurasian subgroups, began migrating to the Federated Malay States (Perak, Selangor, Negeri Sembilan, and Pahang). Their population in the FMS increased from 573 in 1891 to 1,529 in 1901.

In 1931, there were 6,937 Eurasians in Singapore, 2,348 in Penang, 2,007 in Malacca, 4,251 in the FMS, and 468 in the Unfederated Malay States (UMS), which comprised Perlis, Kedah, Kelantan, Terengganu, and Johor.

By 1957, the Eurasian population was recorded at 11,382 in Singapore, 2,428 in Penang, and 1,960 in Malacca. Additionally, there were 5,868 Eurasians in the FMS and 1,053 in the UMS.

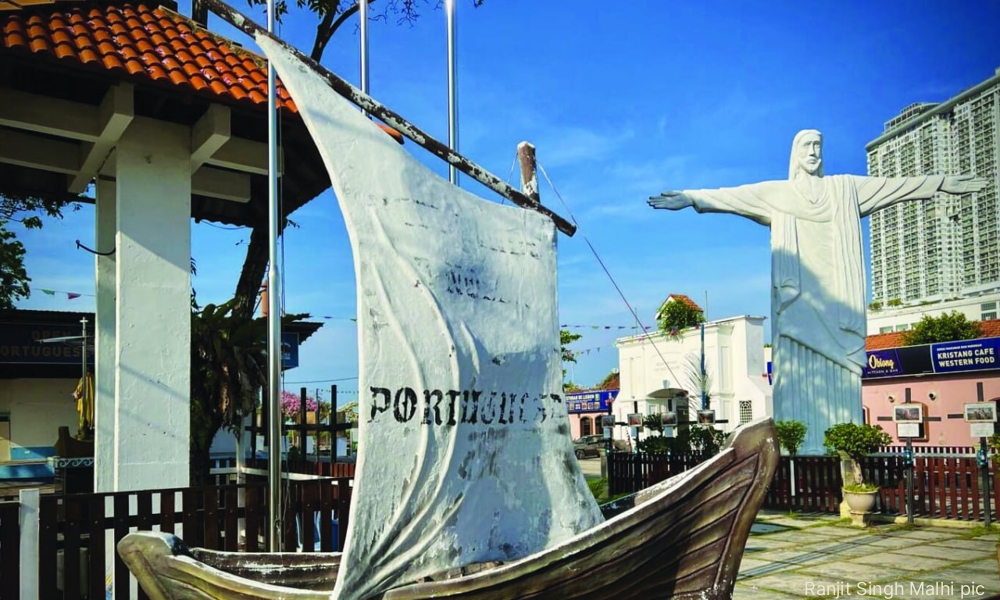

Portuguese Settlement in Malacca

The origins of the Portuguese Settlement in Malacca can be traced to the efforts of Reverend Father Jules Pierre Francois (parish priest of St Francis Xavier’s Church) and Reverend Father Alvaro Martin Coroado (parish priest of St Peter’s Church), who spearheaded the initiative to establish a settlement for fisherfolk and the poor of Portuguese descent.

Father Francois, who was then the president of the Malacca Historical Society, was influential with the British colonial government, while Father Coroado was highly respected by - and closely connected to - the Portuguese Eurasian community. In 1926, both of them appealed to the British authorities in Malacca to establish the settlement.

In 1929, a sum of $50,000 was approved for purchasing, filling, and draining the 28-acre coastal land at Ujong Pasir, Malacca to establish the settlement.

In 1933, the Malacca Portuguese Settlement Committee, comprising community leaders and the two parish priests, began accepting and reviewing applications for lots in the settlement.

The Portuguese Settlement came into existence in 1935 when the first 10 settlers moved in. Originally named “St John’s Village,” as proposed by Father Francois, the settlement holds great significance as a community hub for Portuguese Eurasians, preserving their identity and unique way of life.

It is often referred to as “Padri sa Chang” (The Priests’ Land) because the land for the village was obtained through the efforts of the two Catholic priests.

By 1948, the settlement had 76 attap huts with a population of about 450 people. The first Regidor (headman) of the Portuguese Settlement was Felix Danker.

According to the current Regidor, Oliver Lopez, former Group Chef of Resorts World Genting, the Portuguese Eurasian settlement in Malacca now has 119 houses with a population of about 1,500, including residents from three neighbouring apartment blocks.

Cuisine

Portuguese Eurasian cuisine is a fusion of European, Malay, Indian and Chinese influences, featuring bold flavours and the use of spices.

Some signature dishes include Debal Curry (a spicy curry made with chicken or pork, vinegar, and mustard seeds), Sambal Belacan Kristang (a shrimp paste-based chilli sambal with a unique Eurasian twist), Fried Brinjal with Sambal (eggplant cooked in a flavourful chilli paste), and Sugee Cake (a traditional dessert made from semolina flour, butter, and almonds).

Religion, customs and tradition

Virtually all Portuguese Eurasians are Roman Catholics, a legacy of Portuguese colonisation. Churches such as St Peter’s Church in Malacca, built in 1710, serve as important religious and cultural centres for the community.

Catholic festivals like Christmas, Easter, and All Souls’ Day are widely celebrated, often featuring processions and traditional music. Their renowned St Peter or San Pedro Festival is celebrated annually on 29 June to honour St Peter, the patron saint of fisherfolk.

Attire

Traditional Portuguese Eurasian attire reflects a blend of Portuguese and local influences. Women traditionally wear the kebaya kompridu (long kebaya), often adorned with lace and European-style accessories. This attire has recently been enshrined in Unesco’s Intangible Cultural Heritage List.

Men’s attire consists of European-style shirts and trousers, sometimes complemented by sarongs for casual wear. During festivals and performances, traditional Portuguese-style clothing - including embroidered blouses and skirts for women and colonial-era jackets for men - is worn to celebrate heritage.

Performing arts

Portuguese Eurasian culture is renowned for its rich performing arts traditions. These include the Branyo dance (“flirtatious dance”), a lively traditional dance performed at weddings and cultural events; Kristang folk songs, sung in Kristang Creole and narrating historical and cultural stories; the Farapeirra dance, which is particularly popular among the youth; and Fado music, a melancholic Portuguese genre that has influenced Eurasian musical traditions.

The famous Portuguese song “Jingkli Nona” (Fair Maiden) is closely associated with the Branyo dance.

A little-known fact is that the Malay dance joget actually developed from the Branyo dance. As noted by Mohd Anis Md Nor in his article “Blurring Images, Glowing Likenesses: Old and New Styles in Traditional Dances of Malaysia” (2001), the Branyo dance was “eventually copied by the local Malays and adapted to the Malay dance culture.”

Additionally, the Malay music genre keroncong also has Portuguese influences – the Malay musical instruments “tamborin” (tambourine) and “biola” (violin) originated from the Portuguese.

Among the prominent Portuguese Eurasian singers, musicians, and bands - both past and present - are the late Tony Franco, the late Noel Felix, the late “Papa” Joe Lazaroo, the late Finian Lowe, Royston Sta Maria, Gerard Singh, Lyia Meta, Tres Amigos (Horace Sta Maria, Camillo Gomes, and Ernest Rodrigues), Os Pombos (brothers Jude and Jerry Singho), and The Rozells (James Rozells and Kathleen Rodrigues). Os Pombos, often referred to as the “Alabama” of Malaysia, has been renowned for its country and Western music for over 40 years.

Language

The community historically spoke Kristang Creole, a Portuguese-Malay hybrid language developed during Portuguese rule.

However, with increasing modernisation and the rise of English education, Kristang is at risk of becoming an endangered language due to a diminishing number of users.

Nonetheless, there are ongoing efforts by cultural organisations and academic institutions to revive the language through classes and cultural programmes.

A renowned activist of the Kristang language was the late Joan Margaret Marbeck, also an accomplished actress and theatre director. In 1995, Joan published her first book, “Ungua Adanza” (An Inheritance) and a decade later, her second book “Linggu Mai” (Mother Tongue).

Currently, two other strong advocates of the Kristang language are Sara Frederica Santa Maria and Philomena Agnes Singho.

Sara holds weekly classes at her home in the Portuguese Settlement, teaching children the Kristang language. She also conducts online classes for the benefit of those residing outside the settlement.

Philomena, working in collaboration with the Malacca Portuguese-Eurasian Association under the leadership of Michael Gerard Singho and Universiti Malaya, published a book titled “Beng Prende Portugues Malaka” (Come, Let’s Learn Portuguese Malacca) in 2016. She also posts short videos teaching Kristang phrases on her Facebook page, “Linggua de Mai – Bibe Persempre”.

Additionally, Christine Danker, a former teacher residing in Kuala Lumpur, conducts online classes every Monday at 8pm to keep the Malacca Portuguese language alive. Her class currently has around 10 students - and the number is growing.

While discussing the evolution of the Kristang language it may be pertinent to note the deep linguistic influence the Portuguese have left on the Malay language, with around 400 Portuguese words becoming an integral part of daily speech.

Examples include “sekolah” (school), “gereja” (church), “kereta” (car), “bendera” (flag), “mentega” (butter), “keju” (cheese), “meja” (table), “garpu” (fork), “bantal” (pillow), “kemeja” (shirt), “butang” (button), "sabun” (soap), “tuala” (towel), “jendela” (window), “almari” (cupboard), and “nanas” (pineapple).

Noteworthy contributions

The Portuguese Eurasians played a significant role in the early development of the FMS, dominating subordinate positions such as clerks, technicians, and junior officers in the government and municipalities.

Some, like Tertullian Skelchy, who joined the colonial government of Selangor in 1891, steadily climbed the career ladder and eventually became the head of the Finance Department.

Sir Hugh Clifford, then governor of the Straits Settlements and high commissioner of the FMS, recognised the vital contributions of the Eurasian community.

He acknowledged that, in the early days of the FMS, Eurasians - who were heavily concentrated in clerical services - formed the backbone of the administration, ensuring the smooth operation of the British government. He even admitted that he could not imagine how the government would function without them.

According to Ronald Daus in his book “Portuguese Eurasian Communities in Southeast Asia” (1989), the second generation of educated Portuguese Eurasians became teachers and technicians and among the third generation were lawyers, doctors, dentists and engineers. Additionally, many Eurasian women worked as nurses and secretaries.

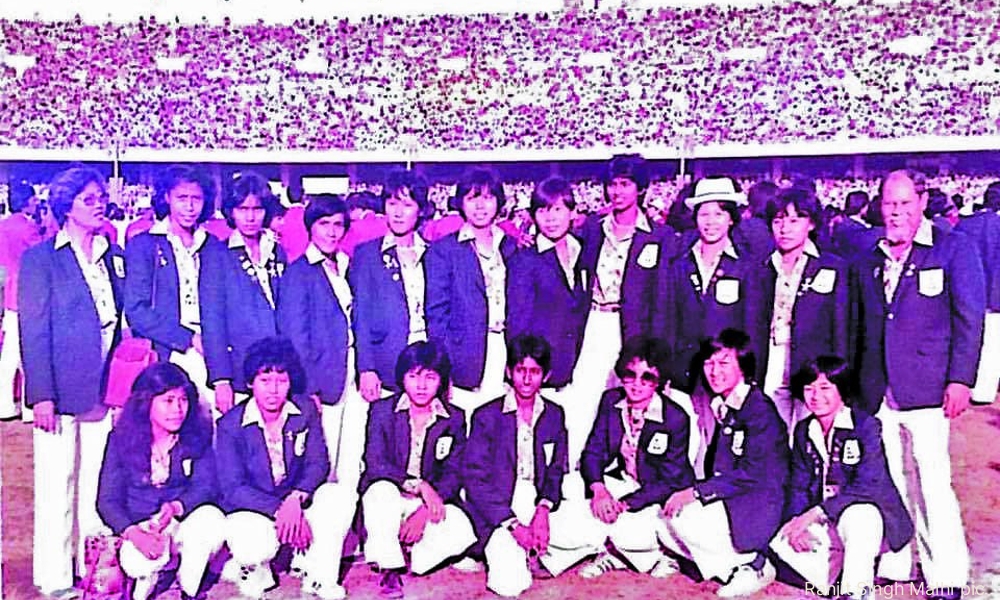

Sports

Despite their small numbers, the Portuguese-Eurasians have made outsized and outstanding contributions to our nation’s sports.

Among their enduring legacies is hockey where 18 Portuguese-Eurasians have proudly represented the nation, with an astonishing eight of them being Olympians: Lawrence Van Huizen, Peter Van Huizen, Stephen Van Huizen, Brian Sta Maria, Colin Sta Maria, Gary Fidelis, Mike Shepherdson, Kevin Nunis, Derek Fidelis, Christie Shepherdson, Henry Sta Maria, Benedict Arias, William Lazaroo, Len Olivero, Brian Carvalho, Paul Lopez, Peter Danker, and Joel Van Huizen.

The late Lawrence not only played for the national team but also coached both the men’s and women’s national hockey teams. His son, Stephen , also served as the coach for the men’s national hockey team. The late Peter Van Huizen was a double international, having represented Malaysia in both hockey and soccer.

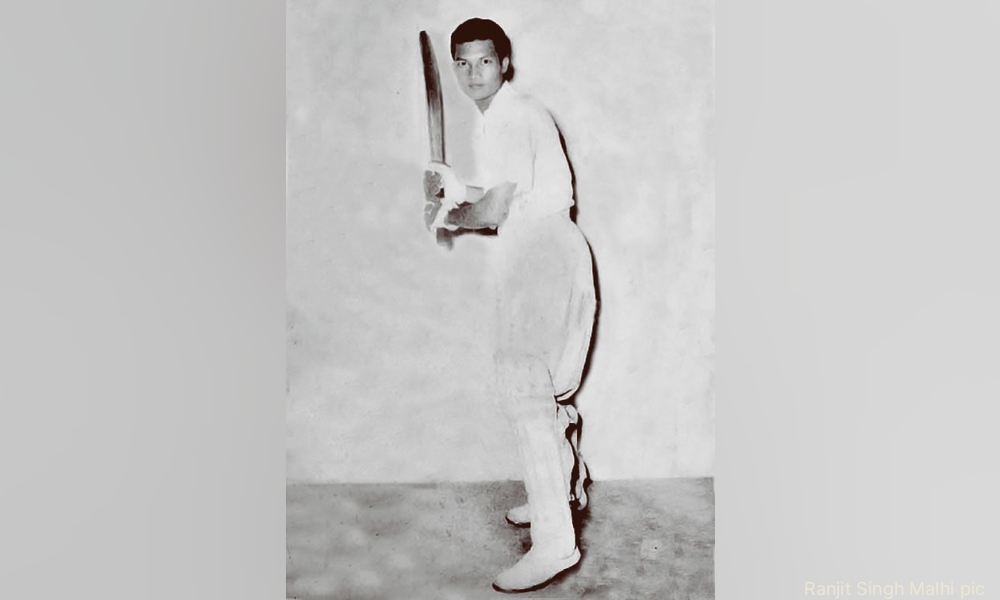

The late Mike and Christie were renowned double internationals in hockey and cricket, showcasing the athletic prowess of the Eurasian community.

Mike holds the unique distinction of being the only Malaysian to have captained both the national hockey and cricket teams. He also earned the rare honour of being the first Malayan named to the Olympic hockey all-star team in 1956.

Regarded as the finest batsman Malaysia has ever produced, Mike set a record by scoring 132 runs against Hong Kong in the Inter-Port match in 1961.

Additionally, he played soccer for Selangor as a goalkeeper. In 2011, he was inducted into the Olympic Council of Malaysia’s Hall of Fame.

Another notable sporting figure is the late Ronnie Ignatius Theseira, Malaysia’s first fencing Olympian, who is regarded as the “Father of Malaysian Fencing”. He established the Malayan Amateur Fencing Association in 1959, which was later renamed the Malaysian Fencing Federation in 1981. He served as its president until 1985.

Among outstanding Eurasian sports figures, the late Daphne Boudville stands out as a triple international. In addition to captaining the national women’s hockey team, she won the bronze medal in the 800m event at the 1965 SEAP Games in Kuala Lumpur and also represented Malaysia in women’s football in the same year.

Cecilia Nunis, captain of Negeri Sembilan’s women’s hockey team, made history in August 1955 by becoming the first woman elected to serve on the Negeri Sembilan Hockey Selection Committee.

Eurasian associations

The Portuguese-Eurasian community established several organisations to safeguard its interests and preserve its culture. The earliest Portuguese-Eurasian association was the Penang Eurasian Association (PEA), established in 1919, with the primary aim of promoting the moral, social, and intellectual advancement of the Eurasian community in Penang. Its first president was Dr Edwin W de Cruz.

The Selangor Eurasian Association (SEA) was formally established on Jan 11, 1920. SEA’s main objective was to promote the political, social, moral, and intellectual advancement of all Eurasians. By the end of 1920, it had 84 members.

The first president of SEA was Alexander Fox, with CR Martin serving as the honorary secretary. Today, it is known as the Selangor and Federal Territory Eurasian Association, with Sheila De Costa as its president.

The Malacca Eurasian Association was formed in November 1934, with a membership of 293 recorded in October 1935. HM De Souza served as its first president, while EW Howell was the secretary.

Subsequently, on Aug 27, 1967, the Portuguese Cultural Society was established in Malacca under the leadership of Bernard Sta Maria, with Mabel de Mello as the organizing secretary.

Half a decade later, in 1997, the Malacca Portuguese-Eurasian Association (MPEA) was established to preserve Kristang culture, language, and traditions.

Since 2001, MPEA’s president has been Michael Gerard Singho, who played a pivotal role in preventing Olympia Land’s bid to reclaim the seafront adjacent to the Portuguese Settlement in the 1990s.

In Perak, the North Perak Eurasian Association, headquartered in Taiping, was formed in 1938, with AS Read serving as president. A year later, the South Perak Eurasian Association, based in Ipoh, was established, with Dr MF De Silva as president and Charles Atkinson as secretary and treasurer. Today, the Portuguese-Eurasian Association of Perak exists, with Jude A Monteiro as its president.

For the record, there were also the Negeri Sembilan Portuguese-Eurasian Association, South Johore Eurasian Association, and the North Johore Eurasian Association.

To represent the broader Malayan Eurasian community in advocating for cultural heritage and social rights, the Eurasian Union of Malaya (EUM) was established in January 1947.

EUM’s first president was CF Gomes of Malacca. Its most prominent leader was G Shelley, who holds the distinction of being the first Eurasian senator. The EUM is no longer in existence.

Prominent Portuguese Eurasians

Among the prominent Portuguese Eurasians who have made significant contributions to Malaysia is Rebecca Fatima Sta Maria, who has served with distinction as the executive director of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) Secretariat (2019–24) and earlier as the secretary-general of the International Trade and Industry Ministry (2010–16).

In the judiciary, Court of Appeal judge Collin Lawrence Sequerah and High Court judge Anselm Charles Fernandis have continued to uphold the community’s legacy of excellence in public service.

In politics, the late Bernard Sta Maria holds the distinction of being the first Portuguese Eurasian elected to the Malacca legislative assembly in 1969 as a DAP candidate, a position he retained through re-elections in 1974 and 1978.

Another distinguished figure in public life is Jeanne Abdullah (born Jeanne Danker), the second wife of former prime minister Abdullah Ahmad Badawi.

Meanwhile, in the entertainment industry, Andrea Fonseka has gained recognition as a model, actress, and television host, having been crowned Miss Malaysia Universe in 2004.

Mention should also be made of Vincent Emanuel Dias, who was conferred a knighthood by the government of Portugal in 1952 for his dedicated service to the Portuguese Eurasian community. As a municipal councillor, he played an integral role in the development of the Portuguese Settlement, ensuring the preservation of its cultural heritage and community well-being.

Further contributing to the legacy of Portuguese Eurasians is CF Gomes who came from a well-established family with ties to the early Portuguese rulers of Malacca. He served as a member of the Governor’s Advisory Council and held the position of Secretary and Accountant of CF Gomes and Company.

Similarly, Maurice Nunis made a lasting impact through his dedicated public service. As a respected representative of the Eurasian community, he served as a member of the Negeri Sembilan state council and retired with distinction as the state treasurer of Negeri Sembilan. In honour of his invaluable contributions, a road in Seremban proudly bears his name.

Portuguese Eurasians have made notable contributions to journalism. Graig Nunis has made his mark as a renowned sports journalist, building a career spanning over 20 years since 1995. He worked in mainstream media and contributed to wire agencies and sports portals.

Currently, he serves as the executive editor of Twentytwo13. Other notable Portuguese Eurasian journalists include Michael Aeria, Gerald Martinez, and the late Tony Danker.

Challenges and the way forward

The Portuguese Eurasian community presently faces several challenges. First, the younger generation increasingly speaks English or Malay, leading to the gradual erosion of the community’s unique vernacular Kristang Creole language.

Second, the community is not classified as bumiputera, limiting their access to certain economic and educational benefits. Third, intermarriage and modernisation have led to diminishing awareness and practice of traditional customs and heritage.

Fourth, many Portuguese Eurasians face economic hardships, particularly those in the Portuguese Settlement, which relies heavily on tourism and fishing. Fifth, the Portuguese Settlement in Malacca faces pressures from urban development and gentrification, threatening its economic livelihood and cultural authenticity.

To ensure their survival in the long run, more heritage conservation initiatives and cultural festivals should be undertaken to keep traditions alive.

The learning of Kristang Creole should be promoted through educational programmes and community initiatives. Government support should be secured to protect the community’s heritage and rights.

Greater employment and business opportunities should be created to uplift the community’s socioeconomic status. Youth participation in cultural preservation should be encouraged through music, dance, and language learning.

The case for Bumiputera status

Since Aug 1, 1984, Portuguese Eurasians have been granted the privilege of investing in Amanah Saham Nasional (now Amanah Saham Bumiputera). However, despite their deep historical roots in Malaysia – dating back over five centuries, with Malacca as their ancestral home – their repeated appeals for full bumiputera status have been denied.

This is in stark contrast to the descendants of Indonesian immigrants who arrived in Malaysia as recently as the early 20th century yet are recognized as bumiputera. Portuguese Eurasians, whose lineage is undeniably intertwined with the land, remain unjustly excluded.

The struggle for recognition is not new. In 1947, the Malayan Eurasian community, in a memorandum to the Consultative Committee, asserted that they were just as much “sons of the soil” as the Malays.

They urged that they be classified as non-Muslim subjects of the Malay rulers and be granted access to the same higher educational opportunities and administrative privileges as the Malays (Malaya Tribune, March 7, 1947).

Almost a decade later, in March 1956, the president of the Eurasian Union of Malaya reaffirmed this sentiment, declaring that the Eurasian community considered itself “a part of the indigenous population” (The Straits Times, March 12, 1956).

Portuguese Eurasians have intermarried with Malays and other bumiputera groups for generations, sharing both bloodlines and cultural heritage.

They have played a significant role in nation-building, contributing far beyond their small numbers. As Margaret Sarkissian, a leading scholar on Malaysian Portuguese Eurasians, aptly observed, the community has achieved “a measure of national prominence that far outweighs actual numbers.” Yet, the economically less advanced members of the community struggle to sustain themselves due to limited resources and a lack of institutional support.

Even former Umno secretary-general Mohamad Rahmat acknowledged this injustice. In 1993, as cited in Gerard Fernandis’s article “The Portuguese Eurasians in Malaysia” (2000), he stated unequivocally: “There should be no problem over their eligibility. If the Chinese, who married Malays, automatically achieved Bumiputera status, then I don’t see why our Portuguese community cannot be considered Bumiputeras.”

If the concept of bumiputera is rooted in indigenous identity, how do we explain the privileged status of some Indian Muslims - who are neither native to the Nusantara nor early settlers - yet enjoy bumiputera recognition or claim it as such?

As rightly stated by the late Khoo Kay Kim, a leading authority on Malaysian history, Indian Muslims can be Malays, but not bumiputeras (Free Malaysia Today, July 20, 2017).

Two examples will suffice. First, a leading textile company of Gujarati Muslim heritage projects itself as “the leader of Bumiputera textile business in Malaysia.”

Second, and even more intriguingly, a Gujarati Muslim currently leads a prominent bumiputera retailers’ association. One cannot help but wonder: Are Portuguese Eurasians – like the Malacca Chettis – being denied their rightful status as “sons of the soil” simply because of their religion?

But, as a historian, it is not for me to speculate why the community has not yet been granted bumiputera status. I can only write based on historical facts. Perhaps, Khoo captured it best when he observed that the Portuguese Eurasian community’s quest for bumiputera status is not a matter of historical verification, but rather a political issue.

Personally, I think, it is time for the government to acknowledge and honour the rightful place of Portuguese Eurasians in Malaysia’s bumiputera framework – not merely as “honorary” bumiputeras, but as full-fledged bumiputeras.

Without official support, this historically significant community risks fading into obscurity. Ensuring their survival is not just a matter of fairness; it is a commitment to preserving a vital part of Malaysia’s national identity.

Conclusion

The Portuguese Eurasian community in Malaysia carries a rich and storied legacy, shaped by centuries of colonial rule, resilience, and cultural intermarriage.

Yet, despite their deep-rooted presence and invaluable contributions to the nation, they continue to face mounting challenges – economic vulnerabilities among the lower-income group, dwindling use of their ancestral language, fading traditions, and a persistent lack of official recognition.

However, their spirit remains unbroken. With dedicated efforts in cultural conservation, education, and policy advocacy, the unique heritage of the Portuguese Eurasians can be preserved for generations to come.

Their history is not just a chapter of the past - it is a living, breathing testament to Malaysia’s diverse and vibrant cultural fabric.

Protecting this community is not merely an act of preservation; it is a commitment to honouring people who have given so much to the nation and who deserve to have their rightful place duly acknowledged. - Mkini

RANJIT SINGH MALHI is an independent historian who has written 19 books on Malaysian, Asian and world history. He is highly committed to writing an inclusive and truthful history of Malaysia based upon authoritative sources.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of MMKtT

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.