KINIGUIDE | The education system in Malaysia is complex and shaped by its multiethnic and multicultural society, historical element, the current social environment as well as education policies.

When the controversy surrounding the implementation of khat or Jawi calligraphy lessons for the primary school syllabus broke out, different segments of society came out with mixed views.

Chinese schools education group Dong Zong hit the headlines when Prime Minister Dr Mahathir Mohamad labelled it as "racist" for opposing the addition of khat lessons for vernacular schools.

Is Dong Zong indeed a racist group as claimed by the premier? What exactly are the Dong Zong and Jiao Zong groups? What do they stand for?

In an effort to promote deeper multiracial understanding, this instalment of KiniGuide will focus on these Chinese schools education umbrella groups and on mother tongue education in the country.

What are Dong Zong, Jiao Zong and Dong Jiao Zong?

In the early days of Malaya, Chinese schools were set up by the Chinese community, particularly through their guilds, via donation drives. School management boards were then set up to establish, manage and operate the schools.

Founded in August 1954, the United Chinese School Committees’ Association of Malaysia, or Dong Zong, is the umbrella body for all Chinese schools management boards in the country's 13 states.

While the individual Chinese school management boards were established under the Education Act, Dong Zong and its affiliate members were created under the Societies Act.

Jiao Zong, which is the United Chinese School Teachers' Association of Malaysia, was established in 1951, four years earlier than Dong Zong.

Jiao Zong was created in response to the enactment of the Education Ordinance based on the Barnes Report which proposed the use of English and Malay as teaching mediums to replace mother tongue education in Chinese and Tamil vernacular schools.

Jiao Zong had advocated that all races should have an equal right to their mother tongue education.

Both Dong Zong and Jiao Zong are the highest Chinese schools education NGOs in the Chinese community. Collectively, they are known as Dong Jiao Zong.

What is a Chinese primary school or national-type primary school?

Soon after the Chinese migrated and settled down, they set up the first Chinese schools with the earliest being established some 200 years ago.

These schools were later incorporated into the national education system in the 1950s.

The Razak Report in 1956, which outlined the nation's educational policy upon independence, recognised the existence of multistream education and allowed for the adoption of mother tongues as the teaching mediums in schools.

The report also classified primary schools into two categories - standard primary schools and standard-type primary schools, both of which became the prototype of the national school and national-type school.

Since then, Chinese and Tamil primary schools have adopted a common curriculum set by the government.

As of 2018, statistics from the Education Ministry showed that out of 7,985 primary schools in Malaysia, 16.26 percent or 1,298 were Chinese primary schools. A total of 518,543 children studied in Chinese primary schools and this constituted 18.78 percent of total primary school pupils in the same year.

Ministry statistics also showed that there were 1,298 Chinese primary schools in 2018 compared with 1,346 schools in 1970, a reduction of 48 schools. Similarly, there were 133 fewer Tamil primary in 2018 compared to 2017. However, the number of national schools jumped by 1,601 schools between 1970 and 2018.

Why the persistent fear that Chinese schools education will be abolished?

The existence and number of Chinese schools are closely related to the government's education policy.

While the Razak Report allowed for multistream education, Clause 12 of the report stipulated the government's "ultimate objective" was to "bring children of all races under a national education system in which the national language is the main medium of instruction".

The report also said that progress towards this goal cannot be rushed and must be gradual. It was this that sparked a deep fear in Chinese schools education NGOs for the future of Chinese schools.

After an uproar by the Chinese community, then Education Minister Abdul Razak (above) decided to not include the words "ultimate objective" in the Education Act 1957.

As such, multistream education comprising national and national-type schools remained in the Education Act 1961. However, Section 21(2) of the Education Act 1961 allowed the education minister to convert national-type primary schools to national primary schools.

This controversial provision was only abolished 35 years later after Najib Abdul Razak took over as the education minister.

Over time, due to migration into cities and urbanisation, there was a need to construct new Chinese schools in urban areas. Existing schools were crowded with some schools having more than 3,000 students.

However, Chinese schools education groups often found that it was challenging to obtain approval for their applications to build new Chinese primary schools.

The scenario in rural areas was completely different where Chinese schools saw a sharp decline in the number of enrolled students. Some schools were reduced to a few dozen students and had to struggle for survival while others had to close outright.

There was also a situation where schools located in densely-populated city centres had to move out to residential areas due to congestion or development.

Under these circumstances, a new (and strange) terminology - "shifted Chinese primary school" - came into being. The term refers to the movement of micro-sized schools (schools with less than 150 students) from rural areas to urban or semi-urban areas as well as the relocation of schools from city centres to residential areas.

Some of these school chose to retain their original name while others renamed themselves. That's why some may find a school that relocated from Imbi to Cheras (in Kuala Lumpur) still called SJK(C) Imbi.

What is a "Chinese independent school"?

Before 1961, the government gave financial aid to multistream secondary schools regardless of their medium of instruction. However, the Education Act 1961 stated that only Malay and English-medium schools could continue to enjoy such allocations.

Once again, Chinese schools education groups objected and as a result, then Jiao Zong president Lim Lian Geok was stripped of his citizenship and his books banned.

Some schools then made the tough decision to toe the government line and become national-type Chinese secondary schools.

Others, however, decided to try and survive on their own so that they could continue mother tongue education and eventually these became known as "Chinese independent schools".

The reason for the Unified Examination Certificate (UEC)

And so, when the Education Act 1961 came into force, the government ceased to provide funding to vernacular secondary schools.

Under such circumstances, the Dong Jiao Zong began to take a prominent role amongst the Chinese independent schools in a capacity similar to the Education Ministry.

Dong Jiao Zong had to create a curriculum for these independent schools. In 1975, it introduced the Unified Examination Certificate (UEC) standardised tests.

As of 2018, there were a total of 60 Chinese independent schools with an enrollment of 66,723 students or three percent of Malaysia's secondary students. Non-Chinese students comprised less than two percent of the student population in these Chinese independent schools.

Of the 3,003 secondary schools nationwide, a total of 2,426 are national secondary schools.

What are students taught in Chinese primary schools?

Some may be curious about what is being taught in the national-type primary schools. In fact, all Chinese and Tamil national-type schools use the curriculum set by the Ministry of Education's Curriculum Development Division.

The curriculum for both national and national-type schools are similar, the difference being in the time spent on each subject. For example, the learning period for English and moral education (or religion studies) in the national-type primary schools are shorter than those in national schools.

In national-type schools for which Tamil and Chinese languages are the core subject, the pupils will spend five to six hours per week on the language.

National schools that teach additional languages allocate two hours for such classes. The additional languages taught include Arabic, Chinese, Tamil, Iban, Kadazan or Semai.

Do Chinese independent school adopt curricula from China or Taiwan?

Some may think that the founders of Chinese secondary schools had adopted curricula from China or Taiwan but this is not so.

Dong Jiao Zong has been setting the school curriculum and conducting UEC tests for junior-middle (equivalent to government schools' Form 1 to Form 3) and senior-middle (Form 4 to Form 6) students.

For their UEC examinations, junior-middle students have to take eight subjects for their examination (some are optional) while there are 22 subjects (including compulsory and optional subjects) in the senior-middle examination.

Bahasa Malaysia is a compulsory subject for both junior-middle and senior- middle students. Beside learning Bahasa Malaysia, Chinese and English, junior-middle students also study mathematics, history and geography.

Upon entering the senior middle level, students will choose which stream they want, either science, arts and commerce, commerce or others.

Controversy often arises over the history subject taught in Chinese independent schools as some question which history is taught to the students.

Junior-middle students are taught the history of Malaysia, Southeast Asia, South Asia, China and Europe as well as ancient civilisations and religions.

Senior-middle students have to study the history of Malaysia and her neighbouring countries in Southeast Asia. This includes the prehistory of the region, the acculturation of Chinese and Indian ancient civilisations, the advent of Islam in Malaysia and the emergence of the sultanate of Malacca.

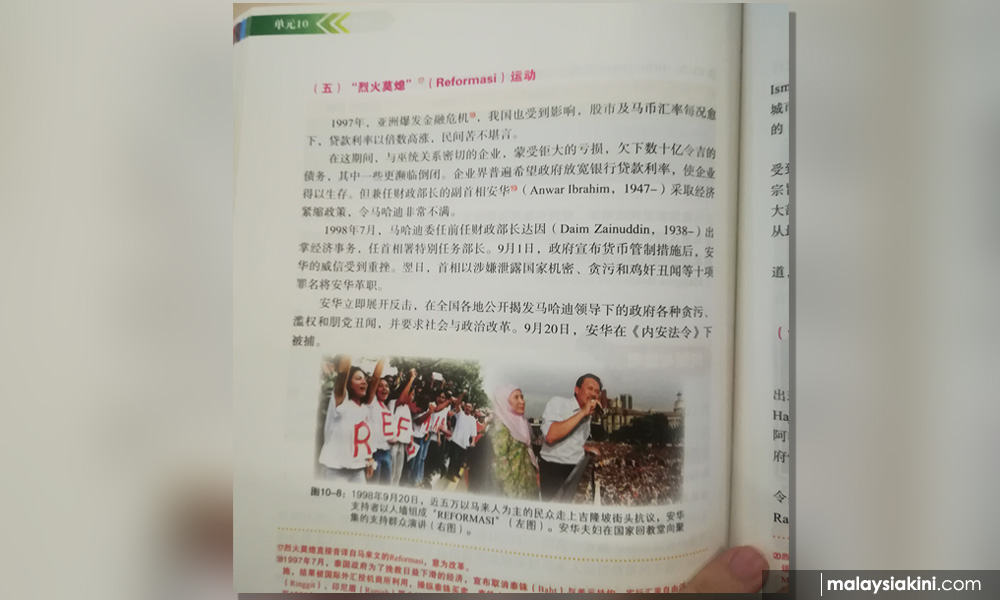

The students also have a chance to learn about the modern history of Malaysia, including the PKR's reformasi movement in 1998 following the sacking of then deputy prime minister Anwar Ibrahim, the electoral tsunami in 2008 and the 1MDB scandal.

It's worth noting that although Dong Jiao Zong sets the overall education policy for Chinese independent schools, each school is given the autonomy to manage its administration and affairs as well as the arrangement of the curriculum.

This, however, has led to a disparity in the Chinese independent schools system.

For instance, some schools will only teach the UEC syllabus while others teach the syllabi of both UEC and the Sijil Pelajaran Malaysia (SPM). Besides that, there are schools teach both syllabi but focus more on the UEC.

Why is there a culture of donation for the maintenance of Chinese schools?

Often, families who send their children to a Chinese school will be asked by their children to donate for the maintenance of the school. Why has this happened when Chinese schools are part of the education system?

There are two types of Chinese primary schools:

- Full-subsidy schools which received a full government allocation (with the school land belonging to the government).

- Partial-subsidy schools which received only a partial allocation (with the school land belonging to either to the school management board or the trustees).

The previous BN administration had repeatedly urged partial-subsidy schools to surrender their school land and turn their schools into full-subsidy schools.

However, Chinese primary schools which turned their land over to the government frequently found themselves lacking the allocations needed to repair and maintain their facilities and infrastructure.

When Deputy Education Minister Teo Nie Ching (photo) was still part of the opposition back in 2017, she visited a Chinese school that was infested with termites despite its full-subsidy status.

She also advocated that all Chinese schools receive equal allocations regardless of land ownership status and stated the government shouldn't treat Chinese schools differently just because of their land status.

In fact, there is no mention of "full subsidy" or "partial subsidy" in the Education Act 1996 and there is no provision that speaks of the different treatment given to schools according to their land status.

Section 16 of the Education Act only classifies schools, including Chinese primary schools, into three categories - government school, government-aided school or private school.

Chinese schools sometimes found themselves lacking in funds for utility bills, expansions of school buildings or classrooms, maintenance and for the purchase of new equipment and furniture.

This has resulted in a phenomenon where Chinese schools raised funds from the public.

This is particularly so for Chinese independent schools which are not "recognised" by the government as they are classified as “private schools” by the Education Ministry. As such, the government does not channel any allocation to these schools.

The four Chinese independent schools in Selangor only started receiving allocations after Pakatan Rakyat (PR) took over power in the state after the 2008 general election.

PR, which in 2008 also ruled Perak, had allocated 1,000ha of land to nine Chinese independent schools to generate income for them and release them from being dependent on government funds. Similarly, the Sarawak government also allocated 2,000ha of land for the same purpose for Chinese independent schools in the state.

These schools enjoyed their first-ever federal funding when Pakatan Harapan took over Putrajaya last year after which Finance Minister Lim Guan Eng tabled the 2019 Budget.

However, Education Minister Maszlee Malik (above) had once commented that Chinese independent schools would not be given funding as they were not part of the national education system.

But after being criticised, the minister then promised allocations for Chinese independent schools under the federal development budget.

Regardless, such allocations are still insufficient for Chinese independent schools to fund their operational expenses. These schools pretty much rely on public donations.

Their students, therefore, often pop up in restaurants and other public places to ask for donations and they also take part in other fundraising events. In turn, the schools have named their buildings, halls or classrooms after donors.

Where do the graduates go?

Most Chinese primary school graduates do not go on to Chinese independent schools.

Statistics from the Education Ministry show that in 2018, around 18.78 percent of primary school students were in Chinese primary schools, but only two percent of students received their secondary education in Chinese independent schools.

Where do the Chinese independent school graduates go? A 2017 Dong Zong study which tracked down 8,655 graduates from 60 Chinese independent schools in 2015, showed that 76.18 percent or 6,593 graduates went on to further their studies.

Among those who chose to further their studies, 56.24 percent studied locally. Of these, 81.31 percent studied at local private universities or colleges, 14.67 percent at foreign universities with local campuses, 0.19 percent in public universites and 3.83 percent unknown.

Some of the students who took the SPM continued their education onto Form Six or did matriculation.

On the 40.41 percent who continued their education overseas, 60.66 percent of these studied in Taiwan. This was followed by Singapore (13.89 percent), China (6.5 percent) and Australia (6.5 percent)

Although the UEC is not recognised by local public universities, the certificate is accepted by many universities globally, including those in Australia, Singapore, the US and the UK.

It is also worth noting that several private tertiary education institutions that have adopted Chinese as their medium of instruction were set up by the Chinese community.

The Nanyang University was first Chinese university established in Singapore in 1956 when the island was still part of Malaya. It later adopted English as its medium of instruction and later merged with the University of Singapore to form the National University of Singapore (NUS).

In the 1990s, the Chinese community set up three Chinese colleges -Southern University College in Johor Baru, New Era University College in Kajang and the Han Chiang University College of Communication - all of which were later upgraded to university college statuses.

About half of the students from these three university colleges came from Chinese independent schools.

What do critics say about Dong Zong and Jiao Zong?

During the previous BN government, Dong Zong frequently faced criticisms, especially from Umno leaders. This included some leaders who are now part of the Harapan government such as Mahathir and Home Minister Muhyiddin Yassin.

During the recent khat issue controversy, Mahathir branded Dong Zong as “racist” after it claimed the government’s move to introduce khat lessons in vernacular schools was a form of “Islamisation”.

“In the past, we created a school called 'Sekolah Wawasan' comprising Chinese, Tamil and national schools all in one campus.

“They (Dong Zong) did not want that because they were apparently scared that their children would mix with Malay children," Mahathir had said.

Other than that, the Perlis mufti Asri Zainul Abidin also likened Dong Zong to a terrorist threat saying the group should be listed as a subversive element in the country.

Ikatan Muslimin Malaysia (Isma) president Aminuddin Yahaya, meanwhile, slammed Dong Zong as a group that only cared about the feelings of the Chinese community but neglected the feelings of other communities.

Does Dong Zong reject racial integration?

Undoubtedly, the initial goal of Chinese education was to provide mother tongue education for Chinese children. But over time, the so-called mother tongue schools no longer cater exclusively to Chinese students as they began taking in non-Chinese students.

Dong Zong's 2017 study showed a decline in the number of Chinese pupils in Chinese primary schools from 2010 to 2017 while non-Chinese pupils increased from 11.8 percent to 18.2 percent in the same period. At the SJK(C) Yuk Chuen in Changkat Jering, Perak, all the students are Malay.

While Chinese primary schools accepted non-Chinese pupils, they still rejected the implementation of single-stream education which they said deprived the right to mother tongue education.

The fear of the Chinese schools education groups stems from the historical development of education policies in the country.

They were particularly sensitive to the integration and unity plan adopted by the government as the 1956 Razak Report had mentioned that the ultimate goal was to make Malay the medium of instruction.

The Education Ministry first advocated a "school integration programme" in 1985 and came out with a Student Integration Plan for Unity (Rimup) the next year. Mahathir then proposed the "Vision School" concept which integrated pupils of multistream schools via the common sharing of a canteen, playing field and hall.

In a statement issued in 2000, Dong Zong disagreed that the vision schools could promote unity via the interaction of their multiracial pupils.

"If this is not built on the premises of equality and fairness, the interaction of multiracial students will not help to boost the understanding between the races. It will create more doubts and tussles due to inequality and will further split the community and create conflicts," it said.

Dong Zong is aware that Chinese independent schools - where Chinese students are the majority - lack an environment for multiracial interaction.

This has prompted it to set up a multiracial and multicultural development task force with the cooperation of Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka and religious schools to hold multiracial activities involving Chinese independent schools.

Amazing article

ReplyDeleteExam test -