China, the world’s most populous country, has benefited most from being a member of the 164-country WTO. It has already become the biggest global exporter. But for the last 17 years since the “Middle Kingdom” joined the free-trading World Trade Organization, foreign companies have been kept in the queue waiting to enter the world’s largest market.

Hence, when the White House announced on Friday about a “Phase One”agreement with China after high-level talks, investors and financial markets were pretty excited. In exchange for Trump dropping a planned tariff increase – from 25% to 30% on US$250 billion worth of Chinese exports – China would purchase up to US$50 billion of American agricultural goods.

But it didn’t take long for the so-called “substantial deal” to look hazy. China said it will only buy U.S. agricultural products based on demand and market prices. Besides, after the U.S. involvement in the Hong Kong protests, which Beijing considered as interference in its internal affairs, did Donald Trump really think that Xi Jinping would help American farmers just like that?

Getting China to buy American agricultural goods was just a trick to get Trump’s 2020 re-election campaign moving on the right track. There’s nothing to stop Trump from slapping new tariff increase (again) right after the Chinese purchased soybeans, corn, wheat and whatnot. By now, Beijing knew there’s no deal until the fat lady sings.

In fact, in order to set the expectations right (in case Trump was hallucinating that he had actually struck a deal), Ministry of Commerce spokesman Gao Feng said on Thursday (Oct 17) that the U.S. must remove tariffs in order for the two countries to reach a final agreement on trade. That means everything should be reverted back to the period where trade war hadn’t started.

A commitment to buy American agricultural goods will definitely not satisfyDonald Trump. Some of the complaints lodged by Trump before he launched his trade war against the Chinese were limited access to China’s domestic market, especially the financial services, trade imbalance, forced technology transfers and intellectual property (IP) theft.

Hence, like it or not, China has to get itself ready when negotiate aboutstructural reforms, intellectual property protections, subsidies and all the things that the U.S. demands. For now, China is not ready to give up the “special and differential treatment” it enjoys as a developing nation at the WTO – a privilege which the U.S. wanted to strip.

Such privilege allows China to provide subsidies for its agriculture and industries, not to mention discrimination against foreign investors who wish to enter its huge market. The United States have been complaining that too many WTO members – about two-thirds – define themselves as developing countries to take advantage of the privileges.

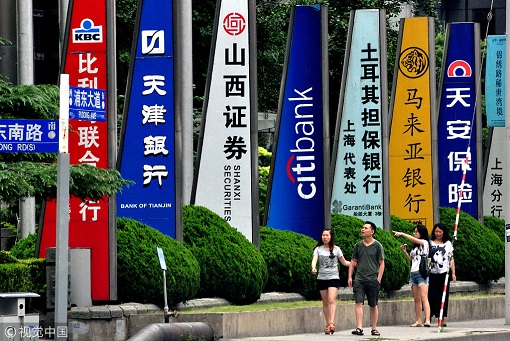

To convince the U.S., and the world for that matter, that the Chinese government is not really the “bad guy” and is willing to speed up the reform process, Beijing has taken advantage of the temporary truce in the US-China trade war. It announced on Tuesday that overseas financial institutions can establish foreign-invested insurance companies in the mainland.

Beijing also finally allowed foreign financial institutions to establish wholly-owned banks in China, and removes the need for prior approval for conducting businesses in the local currency (Yuan). On Friday (Oct 11), the China Securities Regulatory Commission announced the removal of foreign ownership limits in the financial industry, namely in futures, mutual fund and securities companies.

But there’s a catch – licensing and other red tape could take ages. Foreigners who had done business in China know that it’s a familiar script all over again. The Chinese authorities would announce dramatic, but vague promises that raise hopes abroad. Months or even years pass while foreign businesses wait to see regulations, only to be dismayed when costly licensing requirements are imposed.

Hence, even though Beijing has announced the opening of its insurance and other parts of the financial industry further to foreign companies, it may be years before those companies can actually take advantage of the good news. Besides costly licenses and other procedures to be complied, China could curb on the size of the business that foreigners are allowed to operate.

Foreign banks looking to set up their business in China must prepare a minimum capital of 40 billion Yuan (US$5.7 billion). In insurance, foreign investors would face a time-consuming licensing process that requires them to apply in one of China’s 36 provinces and major cities at a time and wait up to a year for approvals. Obtaining approval for the biggest provinces could take up to 10 years.

In 2007, HSBC Holdings, Standard Chartered Bank, Bank of East Asia and Citigroup became the first foreign banks allowed to set up locally-incorporated subsidiaries in China. However, thanks to numerous restrictions on business scopes and operations such as outlet openings, the roughly 40 foreign banks operating in China account for a tiny fraction of a market dominated by state-owned rivals.

There’s another obstacle. The Chinese government controls the movement of money into and out of China – adding to the cost and difficulty of bringing in capital and taking home profits. Therefore, even if the foreign banks are allowed 100% ownership, they cannot take their money out of the country whenever they like without the authorities’ approval.

Still, China wasn’t doing this just to pacify Donald Trump. Opening its own markets gives Beijing leverage to demand the U.S. and other governments (such as the European Union) to let wholly Chinese-owned banks, insurance, and other companies into their markets. It also wants foreign capital, technology, talents, and competition to help improve China’s financial industry.

– Finance Twitter

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.