SPECIAL REPORT | Recent Nepali investigations into the recruitment of workers bound for Malaysia have exposed a network of companies and government agencies in Malaysia and Nepal, which were involved in the alleged “illegal” collection of some Rs5 billion (RM185 million) from over 600,000 people between September 2013 and April 2018.

One company allegedly had links to those close to Ahmad Zahid Hamidi, who was deputy prime minister and home affairs minister at the material time. Zahid, in response, said that he did not abuse his powers and looked forward to being investigated.

In collaboration with the Centre for Investigative Journalism (CIJ) Nepal, Malaysiakinitakes a closer look at how the deals were executed and how personalities linked to Zahid came into the picture.

The Malaysian companies

In November 2014, then home ministry secretary-general Mohamad Khalid Shariff had issued a written directive on the establishment of One-Stop Centres (OSCs) managed by private companies tasked with operating a visa application system for foreign workers.

According to the letter sighted by Malaysiakini, several Malaysian companies were appointed to set up the OSCs and carry out functions related to applications made overseas for a “Visa Luar Negara” (foreign visa, or VLN) to enter Malaysia.

The OSC which specifically handled applications from Nepal, India, Bangladesh and Pakistan was operated by Ultra Kirana Sdn Bhd and its Kathmandu-based affiliate Malaysia VLN Nepal.

Outsourcing of the visa application process had led to a series of various additional charges on Nepali workers bound for Malaysia.

According to details made available by the workers, Ultra Kirana charged each Malaysia-bound worker Rs3,200 (RM118) and therefore was estimated to have collected around Rs1.95 billion (RM4.8 million) from the workers during the material time.

According to records from the Companies Commission of Malaysia, Ultra Kirana’s directors included one Wan Quoris Shah Wan Abdul Ghani.

Repeated attempts to contact Ultra Kirana has been unsuccessful. Malaysiakini managed to reach one Ultra Kirana employee who said the company was aware of the recent allegations made but he was unauthorised to issue a response.

Last month, former Wangsa Maju MP Wee Choo Keong (photo) in a blog post, highlighted Ultra Kirana’s role in offering a similar service in China since 2011, and alleged close ties between Wan Quoris and a former minister.

He also cited The Star’s report on Aug 5, 2012, that quoted then Immigration director-general Alias Ahmad who confirmed that Malaysia will outsource its overseas visa application and processing services, after a successful “pilot project” in China.

When contacted, Wee told Malaysiakini that Ultra Kirana’s role in operating the OSC had started even before the formal November 2014 directive was issued.

In Nepal, meanwhile, on top of the additional visa processing fees, on Jan 15, 2015, another Malaysian company - Bestinet Sdn Bhd - was appointed by the federal government to implement a Foreign Workers Centralised Management System (FWCMS) and biometric screening.

Although the plan was suspended temporarily after an outcry from recruitment agencies due to the increased cost involved, Nepal had on July 8, 2015, decided to approve a “six-month pilot project” for a Bestinet-Nepal Health Professional Federation (NHPF) collaboration to carry out health screenings.

This made it mandatory for Nepalis seeking jobs in Malaysia to undergo biometric screening at 39 centres which charged a Rs4,500 (RM167) fee. It is estimated that 200,000 people had gone through the screening process, which meant that the Bestinet-NHPF joint venture had raked in almost Rs1 billion (RM37 million).

Unnecessary fees

Prior to this arrangement, a Nepali wishing to work in Malaysia would have typically paid Rs700 (RM25) to a recruitment agency to apply for a work visa, while the medical tests would be conducted at any of the 200 government-approved health facilities in Malaysia.

In Nepal, investigations revealed that bureaucrats and politicians received kickbacks for sanctioning the new system, while the new fees that were imposed on Nepali workers were divided between the companies involved.

For example, the Rs3,200 (RM118) visa processing fee did not cover all visa-related costs.

In May 2016, Ultra Kirana Sdn Bhd appointed Malaysia VLN Nepal as the company to collect visa forms and passports to be dropped off at the Malaysian embassy in Kathmandu. A fee of Rs2,800 (RM103.90) was then charged to each applicant.

Bestinet, through its Kathmandu-based agent GSG Nepal, would then charge each applicant Rs3,200 (RM118) for the scanning of passports and fingerprinting process. Another Rs3,500 (RM129) was levied to upload the data online.

Since May 1, 2016, another company called GSG Nepal Pvt Ltd started charging additional fees in the name of “Immigration Security Clearance (ISC)”.

Under the GSG Nepal, headed by executive director Govinda Thapaliya, scanning of the worker’s passport and 10 fingerprints were made compulsory. According to GSG Nepal’s official website, its role was to scan biometric records of the Nepali workers and input their details into the ISC, through an integrated network between the company, the Nepali government and the Malaysian government.

Since the implementation of the ISC, a total of Rs663 million (RM25 million) has been collected from 207,414 workers at the rate of Rs 3,200 (RM118).

Who are the players?

Bestinet Group CEO Mohd Amin Abdul Nor and Nepal Health Professional Federation chairperson Kailash Khadka had reached an agreement on June 20, 2013, to run the FWCMS system purportedly with permission from the Malaysian government.

Mohd Amin (photo below) was formerly from Bangladesh and became a naturalised Malaysian citizen. While several public profiles listed his position as Bestinet Group CEO, Malaysiakini’s check with the Companies Commission of Malaysia found that one Aminul Islam Abdul Nor, believed to be Mohd Amin’s real name, was listed as the company’s director.

Responding to a Nepali Times report which was quoted by several local media here, last Monday, Zahid told reporters that Mohd Amin was not his brother-in-law as widely claimed.

Zahid's younger brother, Abdul Hakim Hamidi, and former minister Azmi Khalid also previously made headlines in connection with Bestinet. Azmi was at the time quoted as Bestinet’s executive chairperson.

In February 2015, about one week after the government announced that it has suspended Bestinet’s services, Azmi revealed that the company has not been awarded an official government contract, but it proceeded to set-up operations at over 200 clinics from 11 migrant workers source countries.

Abdul Hakim’s company, Real Time Networking Sdn Bhd, was eyeing a deal to provide a management system for the government’s plan to bring in 1.5 million workers from Bangladesh through a new business-to-business system.

Abdul Hakim was listed as executive chairperson in Real Time Networking’s proposal submitted to the Home Ministry on June 17, 2015, and other correspondences. Checks with the Companies Commission of Malaysia show that Abdul Hakim is not listed as an official in the company.

Instead, his son Mohd Akmal, 25, is a director of Real Time Networking, along with former Home Ministry deputy secretary-general Raja Azahar Raja Abdul Manap, and one Salihah Kasim, 25.

At the time, it was noted that Real Time Networking’s online system was similar to the system provided by Bestinet. Hakim went on to refute suggestions of nepotism in relations to the deal.

Back in Nepal, on June 2016, a committee led by Joint Secretary Govinda Mani Bhurtel recommended that the government prevent Bestinet and other private firms from overcharging Nepali workers.

When pressure mounted to shut the Bestinet biometric system in Nepal, then labour minister Dipak Bohara arrived in Kuala Lumpur to "inquire about the condition of Nepali workers in Malaysia."

On June 30, 2016, Bohara (above right) held a meeting with Abdul Hakim (above left) at a hotel in Kuala Lumpur, which sources said was pre-arranged by Amin. Upon Bohara’s return, the biometric system was allowed to continue as usual.

Around the same time, online portal Suara TV quoted Amin who denied that he was awarded a “fast-track” citizenship, believed to be a response to earlier reports which highlighted his alleged ties with Zahid in relations to Bestinet’s role in the Bangladeshi worker labour recruitment scandal.

Bestinet denies claims of excess fees

Meanwhile, Bestinet in a statement to Malaysiakini, denied all claims made against the company, particularly with regards to collections of alleged extra fees.

Bestinet said the allegations were “entirely false” and reiterated its commitment to conducting its business in a responsible manner.

"In every labour source countries, there are four service providers appointed by the Home Ministry to carry out different functions required by the Malaysian government," said the company.

Bestinet said the four companies were each appointed to provide one service - Immigration Security Clearance (ISC), health screening (Bio-Medical System), One-Stop Centre and Visa Luar Negara (VLN).

"Bestinet only provides service for 'Item 2' which is the health screening (Bio-Medical system).

"The other three services are conducted by three different service providers who are not related to us," said the company.

Responding to claims it had profited from various extra charges imposed on workers, Bestinet said it only collects RM100 for the bio-medical system which was approved by the Malaysian government, while other charges were collected by the other three service providers.

“We would also like to highlight that if after registering, a worker fails the eligibility verification, there will be no charges for the services and the workers will also not have to undergo the health screening.

“We would also like to emphasise that ISC (Immigration Security Clearance), OSC (One-Stop Centre) and VLN (Visa Luar Negara) services are not provided by Bestinet and Bestinet is not related to the providers of these services and any Kathmandu-based agents,” it further said.

At present, however, the company said since the Nepali government has stopped its citizens to come and work in Malaysia, their system is also currently not in use.

Bestinet, meanwhile, also denied any ties with Zahid (photo).

In its statement, Bestinet said the company was only a service provider for the Bio-medical system while the biometric screening mentioned in the article was one of the modules of Bestinet’s own pioneering and award-winning Foreign Workers Centralized Management System (FWCMS).

It said FWCMS was a holistic foreign workers' management system developed specifically for governments and was recently recognised by UN-based World Summit Awards as one of the world’s 40 best digital projects that help meet the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals.

“The idea of FWCMS was first presented to the Malaysian government in 2004, the government reviewed the proposal in 2011 and approved the implementation of the system under a Proof-of-Concept (POC) basis in 2012, before Zahid became the Minister of home affairs,” it said.

On allegations that Bestinet had received money from workers via the “illegal” hundi system from Nepal, the company explained that it will be notified by email from recruitment agents in Nepal with details of bank payment and receipts.

The hundi system is defined as an informal remittance transfer channel which was declared as illegal under Nepali law as it allows such transfers to be conducted without a paper trail to its original source.

“Our account department will then verify the deposit and receipt accordingly and top up the agent’s e-wallet in the system.

“Tax invoice and receipt will be sent to the respective agent by email generated automatically by the system,” Bestinet said.

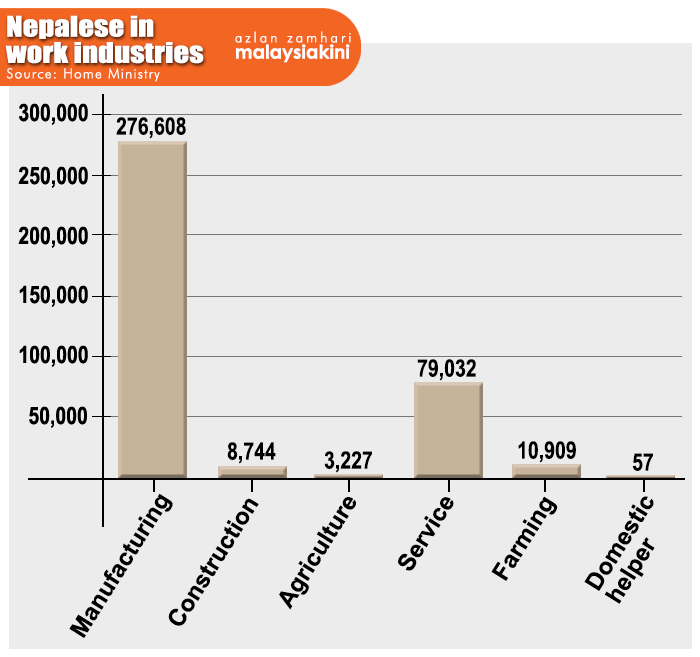

How big is the Nepali workforce here?

Officially, Nepalis make up the second largest source of migrant labour in Malaysia after Indonesians.

As of June 30 this year, according to Home Ministry figures, there were a total of 1,747,154 migrants workers from 13 countries who are legally allowed to work in six approved sectors.

From this figure, Indonesia tops the list as a source country with 688,641 workers here (close to 40 percent) followed by Nepal which has 378,577 registered workers (21.67 percent).

While the government has been lauded for its move to crackdown on undocumented migrants here, concerns were also raised over the failure to address the root cause of how they continue to end up being caught in such a vulnerable position. Similar calls were made by rights groups in Nepal over the failure of its own government to protect their workers.

Klang MP Charles Santiago had called on the Malaysian government to "tackle corruption" surrounding the labour recruitment process as one way to end the cycle of undocumented migrant workers.

Human Resource Minister M Kulasegaran has announced in Parliament that Malaysia and Nepal are in talks to enter into a new agreement over recruitment and placement of its citizens as workers here. - Mkini

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.