Last week, Malaysia’s ex-diplomat, Redzuan Kushairi, brought up a serious question about the current state of our foreign policy. According to him, the present Pakatan Harapan government has largely followed the ‘old’ foreign policies of the previous Mahathir 1.0 administration and as such, it is inadequate to adapt to the present global situation.

This is in light of the emergence of new powers such as China and Russia, a situation that exerts pressures on the smaller nations (including Malaysia) in terms of their engagements with the wider world.

To be exact, Redzuan (photo, above) provided three examples which the present Mahathir-led Harapan government is still banking its foreign policy on, namely the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM), the Group of 77 and Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC). While these were the cornerstones of Malaysian foreign policy in the past, as he understood, they, however, are losing relevance in the disruptive great games between new and existing powers today.

What Malaysia should do now, instead, is to establish cooperation with individual countries such as Turkey, Tunisia and Indonesia on matters related to the Islamic world while at the same time, train more specialists on China and Indo-Pacific alliances to ensure our relevance in the international arena.

Coming from a diplomatic background, Redzuan’s revelations are both timely and necessary for Malaysia, which underwent a regime change last May. Just like how national politics needs to respond to a new political environment, the same it is for our foreign policy.

Being challenged by the disruptive global and regional environments of the day, a new foreign policy is required to service and advance our national interests abroad. But before moulding a new foreign policy, there is a need to consider three fundamental questions beforehand.

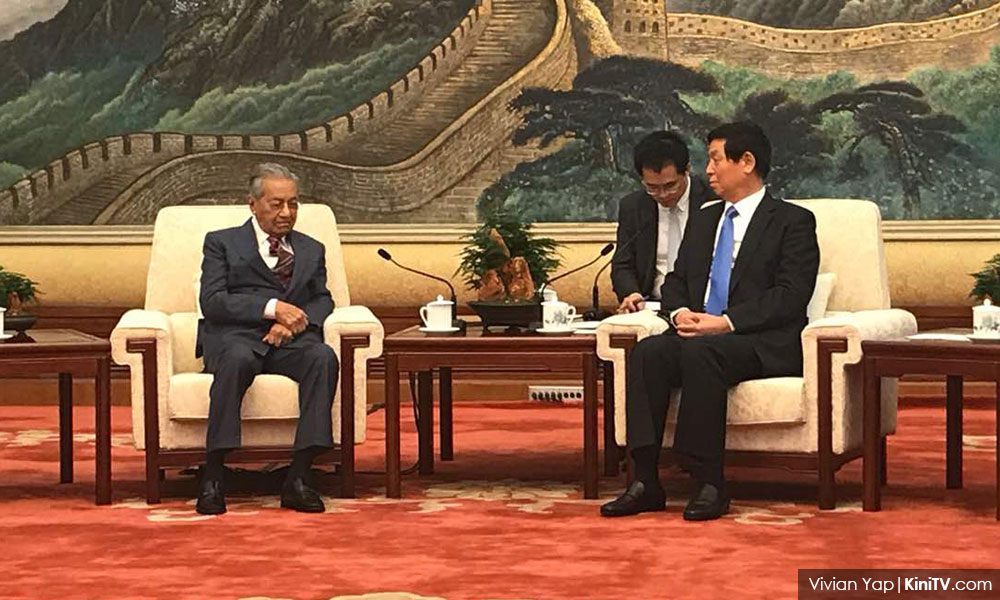

First and foremost, how does Malaysia posit China in the current world order? This is the most thought-provoking question thus far, considering both Prime Minister Dr Mahathir Mohamad and his named successor, Anwar Ibrahim, have consecutively brought up the conventional notion of developing versus developed nations. In Mahathir’s term, he cautioned the danger of a new version of colonialism for developing nations while for Anwar, it is Nehru’s Asian solidarity movement against the then Western imperialism of several decades ago.

Be it Mahathir or Anwar, both do not explain whether China is included within their arguments, a further indication that they have not settled the question of China in their long-standing notion of developing versus developed nations.

While still one of the developing nations, China is also a superpower-in-the-making today. Be it its economic prowess, military superiority, technological innovation or international influence, it is a misnomer to view the present China the same as the old China of the 1990s or even, during the Cold War period. Thus, this begs the earlier question: how does Malaysia place China in the current world situation?

Should we view it as a big developing nation as in the past or should we accept China as one of the great powers, just like the US? And if we take the latter’s stance, is it not the time for us to abandon the conventional “developing vs developed” dichotomy and start a whole new approach in our foreign policy pursuits?

Any adjustment of this scale will require not just perceptual change from our leaders but also, how Malaysia deals with a dominant China today.

Western world cannot be neglected

Second, when speaking about a disruptive global situation, there is no way that we can neglect the Western world itself. Hence, the second question is, how do we situate the Western powers in our new foreign policy? For a start, Malaysia has been enjoying long-standing ties with the UK, Australia, New Zealand and Canada ever since its independence in 1957.

Not only are these the earliest countries to recognise Malaysia as an independent state but some of them are also partners of the Five Powers Defence Arrangement (FPDA), to which Singapore and Malaysia belong.

While our bilateral trade with these countries is relatively lower than that of China’s, it does not mean these Western states are insignificant to us. For one, the enduring socio-cultural, business and military ties we have with these nations only highlight that there exist close bilateral ties among us.

As Trump’s “American First” policy, Brexit and China’s influence-spreading send shockwaves to major countries in the West, it is foreseeable that they are making their “return” to our part of the world. While the UK is eyeing to make a Southeast Asian comeback through economic and other areas of engagements, Canada, too, has to navigate itself away from its dependence on the American market into this largely untapped, emerging Asean market.

Australia, meanwhile, is eagerly cooperating with India and Japan as part of its Indo-Pacific collective effort to build their share of influence against the increasingly dominant China in Southeast Asia. All these developments are enveloping us today and it is for us to decide how we should situate these Western powers in our new foreign policy, without compromising our sovereignty, independence and self-determination.

And no doubt, fostering close relations with them may also, in turn, affect our policy vis-à-vis the US, Japan and India.

Third, in terms of our relations with the Islamic world, Redzuan made a good argument in that we should not pin too much hope on the OIC as what we did in the past. With the Yemen war ongoing, not only is there an actual risk of being dragged into a proxy war between Saudi Arabia and Iran, but it also puts into question the effectiveness of the Islamic organisation in managing the complicated situation in the Middle East.

Instead, as suggested by the ex-diplomat, it is more worthwhile to work with individual Islamic nations (such as Indonesia, Turkey and Tunisia) that share the same orientation as Malaysia in maintaining neutrality and enacting collective actions within the larger Muslim world.

What Putrajaya should ask at this point is, how do we work with these countries and engineer collective actions in the long-term? This will entail envisioning the forms of cooperation with like-minded Muslim nations, areas of collective actions as well as the possible establishment of mechanisms for this purpose.

More importantly, Malaysia can also explore ad hoc or visionary cooperation with other like-minded nations in the Islamic world and beyond in terms of preserving global peace, security and development goals.

Overall, these three fundamental questions are also reflections of the past versus the present geopolitical situation in the region and the world.

At the time that the 15-member Consultative Council on Foreign Policy is deliberating a new foreign policy framework for Malaysia, it is important to ensure that such a framework will eventually posit Malaysia on a path that allows it to manoeuvre its foreign policy in response to the disruptive regional and global politics today.

Answering these three fundamental questions will be a good start.

KARL CL LEE is a PhD candidate at the School of Arts and Social Sciences, Monash University (Malaysia campus). He was also visiting scholar at the School of Politics and Public Administration, Guangxi University for Nationalities (GXUN) under the 2017/2018 Chinese Government Scholarship (Bilateral Programme).

SK CHIA is researcher for Anbound Research Center (Malaysia), a subsidiary of Anbound, a leading independent think tank headquartered in Beijing. It is also a consultancy firm specialising in China-Asean cooperation. His e-mail is siangkimchia@anbound.com - Mkini

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.