For decades, Kampung Sembulan Tengah sat quietly on the edge of Kota Kinabalu’s city centre, close enough to feel the pull of urban growth, yet holding on to the identity of a village formed from resettlement rather than ownership.

That balance has been under pressure for years and may be reaching its breaking point.

Last weekend, more than 70 landowners gathered in what appeared to be a last collective effort to gain clarity over their land status amid the advance of Sabah’s Sembulan Urban Renewal Scheme.

The meeting took place against the backdrop of unease following Kota Kinabalu City Hall (DBKK) enforcement officers demolishing several dilapidated houses in the area a few weeks earlier.

The structures occupied by renters were in poor condition and posed safety risks.

While the demolitions did not involve landowners or compensation, they heightened concerns over how quickly physical change could arrive in an area where land status remains unresolved.

From Sembulan Lama to Sembulan Tengah

Sembulan Tengah is an extension of the original Sembulan area, or what is known to locals as Sembulan Lama, near Saadong Jaya, nearer to the city centre.

Sembulan Lama was established in the nineteenth century during the colonial period and formed the historical core of the area.

Later in 1960, Sembulan Tengah emerged as part of the British’s organised resettlement plan to allow the expansion of Jesselton town under the British crown colony.

The resettlement under the Jesselton Town Board Low Cost Housing Scheme was intended to accommodate families displaced by the expansion of Jesselton town, now Kota Kinabalu, southwards towards Tanjung Aru.

Under the programme, 205 lots were allocated, including to residents from Sembulan Lama and neighbouring districts such as Putatan, Papar and Tuaran.

Records show that 71 lots were allocated to Chinese residents, with another 105 distributed to other settlers.

Land was issued under town or temporary lease titles rather than permanent ownership, a feature that is now being challenged by the Sembulan Tengah people and their children.

Turned into squatter colony

By the 1980s and 90s, political instability in Sabah, urban migration and rising land values began reshaping the area’s social and physical landscape.

Some original residents sold their properties. Others rented out their homes. Many remained, occupying land held under leases rather than titles.

During this period, parts of Sembulan Tengah also became associated with social problems, including illegal settlements arising from migrant inflows and drug activity.

Some long-time residents, including members of the Chinese community, later cited these conditions as reasons for leaving the area or renting out their houses.

This resulted in urban migration and undocumented migrants who came to Kota Kinabalu for work or business finding a home in the village due to the cheap rentals.

Not long after, coastal land near the village was redeveloped to make way for the highway linking the area to the city centre, and malls began to mushroom along the highway.

This gradually reduced the size of Sembulan Tengah, leaving it as a pocket of mangrove water village wedged between highways, commercial developments, and shopping complexes.

Soon, it too may be absorbed into the growing concrete jungle.

Urban renewal picks up pace

The Sabah government had drawn up an urban renewal scheme for Sembulan Tengah in the early 1990s.

Agreements with private companies were signed between 1993 and 1997, but progress stalled for years amid commercial and land-related disputes.

Momentum returned in May 2024, when the Sabah cabinet approved an updated version of the Sembulan Urban Renewal Scheme, clearing the way for the second phase of redevelopment.

While the proposed compensation for Sembulan Tengah residents remains unclear, Malaysiakini has learnt that eligible landowners may be offered a condominium unit each, along with RM50,000 in cash compensation.

The information has yet to be officially verified, and residents who gathered for a meeting last Sunday indicated they, too, were unsure if that’s what was on the table for them.

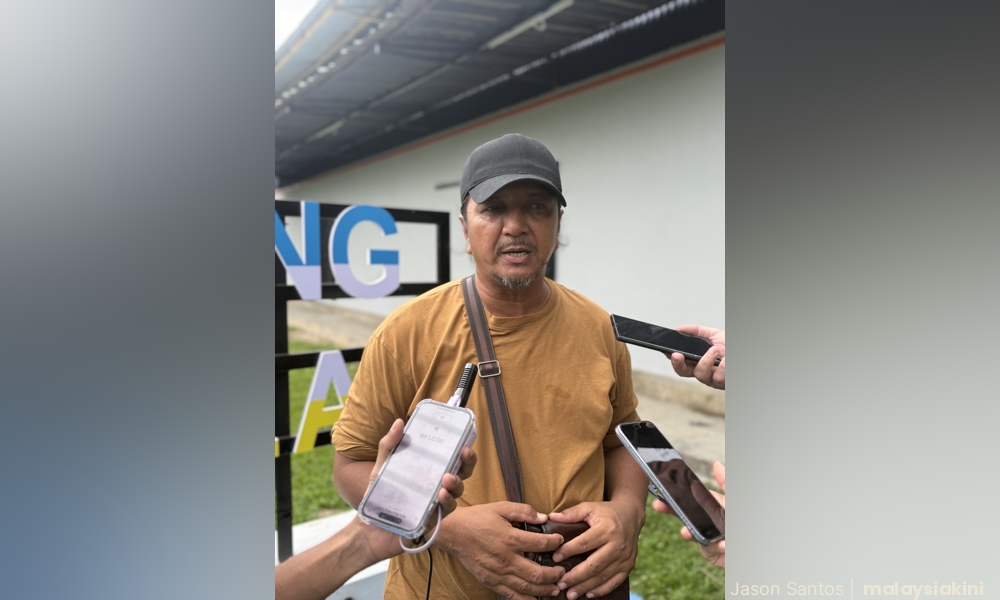

Addressing residents at the meeting, Kampung Sembulan Tengah Welfare Association chairperson Osman Omar Khan stressed that the gathering was not intended to block development, but to seek clarity.

“We are not opposing development. We are asking for certainty,” Osman said.

Residents are seeking written assurances that no further demolition, land filling or earthworks will take place until all landowners and heirs are consulted and compensation discussions are concluded.

Osman said such assurances were previously verbally conveyed during a meeting with DBKK officials on Dec 23.

However, the demolition of some structures in the village a few weeks ago has the residents worried.

“After the recent demolition, the land cannot be disturbed or encroached upon by any government agency or developer until landowners are called to discuss compensation and development,” he said.

Putatan Umno division chief Jeffrey Nor, who attended the meeting at Osman’s request, said while some demolitions were justified on safety and enforcement grounds, there must be discretion when it comes to long-time residents living on expired leases.

“These are people who have lived there for a long time. You cannot just remove them without giving them compensation,” Jeffrey said.

According to Osman, 64 land titles in the area remain active, while 104 have expired, based on cross-checks conducted with residents. - Mkini

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.