The new Malaysian Prime Minister’s reviews of the key water-supply deal with Singapore and of the planned costly high-speed rail link from Kuala Lumpur to the city-state are only visible signs of a different — and more charged — Singapore-Malaysia relationship.

The key problem for Lee Hsien Loong’s People’s Action Party (PAP) is that developments north of the Johor-Singapore Causeway have exposed vulnerabilities at home. The PAP has become the longest-governing incumbent party in Southeast Asia, and it no longer has undemocratic immediate neighbors. Mahathir’s Pakatan victory mirrors the PAP’s worst fear: its own possible defeat.

Worse yet, some of the factors that contributed to the loss of Barisan Nasional (National Front) are also present in Singapore. The first is the challenge of leadership renewal. Over the past three years, the PAP has been locked in a battle over who should succeed Lee, 66, as prime minister, with the fourth generation (4G) leaders on display.

Among the leading contenders are Chan Chun Sing, the Minister for Trade and Industry and former army chief, Finance Minister Heng Swee Keat, former Managing Director of the Monetary Authority of Singapore and Ong Ye Kung, the Minister of Education and Second Defense Minister.

The problem is that these leaders are 4G without the connectivity. They are in a highly elitist party, largely unable to relate to ordinary Singaporeans. 4G leaders also suffer from the same issue that haunted the National Front, namely they are embedded in the system. Emerging from within the party and government, particularly the military, they are from the system and are seen to be for the system. The intertwining of the PAP and the bureaucratic state has created singular agendas and resulted in a distancing from the electorate and its needs.

For the first two decades of Singapore’s existence after independence in 1959, PAP secured all the seats in the legislative assembly. Since 1984, opposition politicians have won seats despite what the government’s critics describe as the sustained political harassment of opponents and the repression of public protests, combined with the alleged manipulation of electoral boundaries.

In the last election in 2015, PAP secured 83 out of 89 seats with 70% of the vote. Since that resounding victory, more conservative forces within the party have gained ground. Despite their popularity, reform-minded leaders such as Tharman Shanmugaratnam and Tan Chuan-Jin have been pushed aside in favor of conservative alternatives. At the same time, Singapore’s system has moved in a more authoritarian direction, with curbs on social media and attacks on civil society activists.

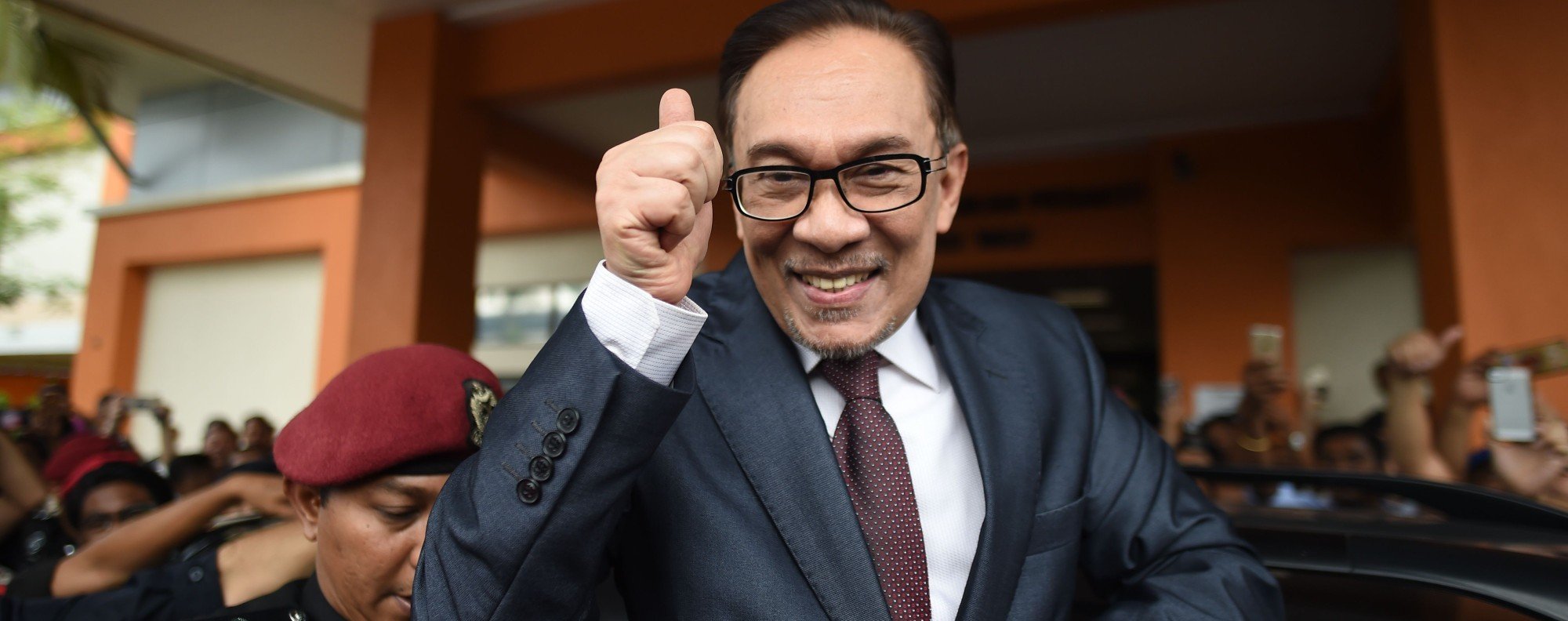

Tharman Shanmugaratnam

Prime Minister Lee, the son of Singapore’s founding father Lee Kuan Yew, is making the same mistake Najib did after the 2013 polls. He is depriving the system of a necessary valve for dissent, and moving the country away from needed reforms. He has failed to recognize that greater openness and policy reforms were integral parts of the PAP’s 2015 victory. The dominant mode has been to attack the Worker’s Party, its leaders and other opposition figures. These moves do not show confidence in a more open and mature political system — or even in the PAP itself.

At the same time, rather than being an asset to his party, Lee is becoming more of a liability. This is the same trajectory that occurred for Najib. Questions have been raised about Lee’s leadership from the very public “Oxleygate” row with his siblings over their father’s home to the managing of Temasek, the republic’s sovereign wealth fund, by his wife Ho Ching.

Singapore’s handling of scandal over 1 Malaysia Development Berhad (1MDB), the Malaysian state-run investment fund which saw millions of dollars siphoned out on Najib’s watch, will be in the more immediate bilateral spotlight; assessments will be made as to whether Singapore responded effectively to the alleged malfeasance and whether in fact Singapore’s purchase of 1MDB bonds strengthened the fund.

Meanwhile, in Malaysia, Mahathir’s readiness to deal with 1MDB signals a willingness not only to clean up the system but to begin much-needed economic reform. Singaporeans will see obvious parallels with their own country’s economic policies.

Singapore’s gross domestic product growth is expected to reach 3% this year, which is a significant drop from a decade ago. Importantly, much of this growth is being driven by public spending (as occurred in Malaysia under Najib), notably on infrastructure. New jobs are not being created in Singapore at the same high rate as in the past. Even more constraining, PAP continues to rely on immigration as a driver of growth, failing to move on from using a combination of low-cost labor and imported foreign talent to expand the economy. Population pressures remain real for ordinary Singaporeans, who continue to feel displaced. They are disappointed with the PAP’s tenacious grasp on old and unpopular models for growth.

The pendulum of discontent has swung against the PAP. The government opted to increase water prices by 30% in 2017, and this year indicated it will raise the goods and services tax (GST) from 7% to 9%. The electricity tariff has risen by 16.8% to date this year alone. The cost of living remains high; Singapore has topped the Economist Intelligence Unit’s list of most expensive cities to live in for five years running. High costs are compounded by persistent inequalities that are increasingly entrenched. The Gini coefficient is at 0.46, but income gaps are deeply felt. Many locals feel they are being impoverished on account of foreigners. The social reform measures introduced for the “pioneer generation” (people born before 1950), and increased handouts before the 2015 polls, are being seen as inadequate to address the current social needs of disadvantaged communities.

Changes in Malaysia have reduced Singapore’s regional comparative advantage. It is not just about greater democracy and changes in governance next door but also the attention “New Malaysia” draws to how Singapore has remained locked in the past, moving away from embracing an alternative future.–Bridget Welsh

By comparison, Malaysia has removed the unpopular GST, and reform pressures for addressing contracting social mobility and inequality are substantial. Malaysia is now seen as a potential role model in areas of governance. For example, greater transparency and attention to inclusivity are evident in the multi-ethnicity of new government appointees. Singapore’s 2017 Malay-only presidency contest in contrast sent a signal of exclusion and an embrace of race-based politics. This is being compounded by the fact that Malaysia is being seen as bucking regional authoritarian trends, promising substantive political reforms and the removal of many of the draconian laws that Singapore has on its books.

Changes in Malaysia have reduced Singapore’s regional comparative advantage. It is not just about greater democracy and changes in governance next door but also the attention “New Malaysia” draws to how Singapore has remained locked in the past, moving away from embracing an alternative future.

WRITER: Dr Bridget Welsh

– https://dinmerican.wordpress.com

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.