The results of the Umno polls are in and the internal pressures for meaningful reform have been thwarted.

It would appear that the election of Najib Razak’s proxy Ahmad Zahid Hamidi as president has prevented the party from bringing about needed changes from within. A closer look at the election campaign and results, however, shows that Umno is seriously divided, and there is in fact an ongoing revolt within the party that is far from over.

Najib pity party

The struggle between “old” politics – money, warlord pressure, insularity, entitlement, racial rhetoric and unquestioned loyalty to the leader – and “new” politics – ideas and policies, more national and substantive engagement on issues and with communities, and greater empowerment of the grassroots – played itself out in the party campaign. The dominant narrative of the party election was one of reform.

History was made with a televised public debate, brought about by Tengku Razaleigh Hamzah’s challenge to his competitors, and there was an unprecedented level of competition for leadership positions. Unlike the hotly-contested 1987 party election, the 2018 Umno election provided clearer choices for the direction of the party, as opposed to primarily supporting different personalities and camps.

The outcome of the election revealed the control of vested “old” interests in the party with the election of Zahid and many in his camp, notably vice-presidents Ismail Sabri Yaakob and Mahdzir Khalid and Wanita chief Noraini Ahmad.

Over half of the incumbent division chiefs/deputies were returned, with 37 percent of these unopposed. The share of Wanita incumbents returned was even higher, with over half of these 56 percent contested. At the supreme council, the results show a predominance of incumbents as well. The forces for status quo held onto power.

They did so largely by using money and pressure politics – “instructing” delegates how to vote. “Duit raya”, or rather more aptly “duit rakyat”, was used to buy delegates, with some envelope payouts allegedly reaching over RM1,000 per delegate. These tactics were combined with the feeding of the view on the need to defend the party against “enemies” and the mistaken delusion that it was a matter of time before Umno would get back to power through alliances with new partners and divisions within the ruling Pakatan Harapan.

The main proponent of this defensive/denial politics is Najib, who used his influence to assure that his proxy(ies) won so that he can continue to feed on sympathy within the party and secure a (mistaken belief in a) safe landing for himself. Many of the warlords and division chiefs, who were responsible for keeping Najib in power after the 1MDB scandal was revealed, joined the ‘Najib pity party’ out of self-interest and self-preservation, and pressured the delegates to toe the line.

The revolt

Many of the delegates rejected these pressures, some outrightly in a revolt and an embrace of “new” politics, while others through more indirect resistance. The results show that while “old” forces won pluralities, they did not win consistent majorities. The number of branches that favoured reform candidates – Razaleigh and Khairy Jamaluddin – outnumbered those that favoured Zahid, 53,054 to 39,197, and votes within an overwhelming majority of branches were sharply divided.

The fact that the reform camp was divided, split between Razaleigh and Khairy, undercut its success.

Yet the “winner take all” electoral college system of the election also weakened the vote for reform, as those incumbents holding position had more sway in the final outcome as they comprised the bulk of the 160,000 delegates.

If Umno had a more democratic electoral system with all of its grassroots being able to vote, the outcome would have revealed that the majority of the party members want change. They are trapped in an undemocratic electoral system that disempowers members and advantages incumbents.

The results show that despite this imbalance, the revolt in Umno is strong. The supreme council contains many of those closely linked to the Khairy camp, notably Zambry Abdul Kadir, Abdul Rahman Dahlan and Reezal Merican Naina Merican, among others.

Annuar Musa’s defeat is perhaps the most obvious sign of this discontent. He was perceived as the candidate closest to the Najib/Zahid camp and most actively reportedly engaged in vote buying. In a head-to-head contest, he lost to Mohamad (Mat) Hassan, Khairy’s cousin and seen as more aligned with reforms.

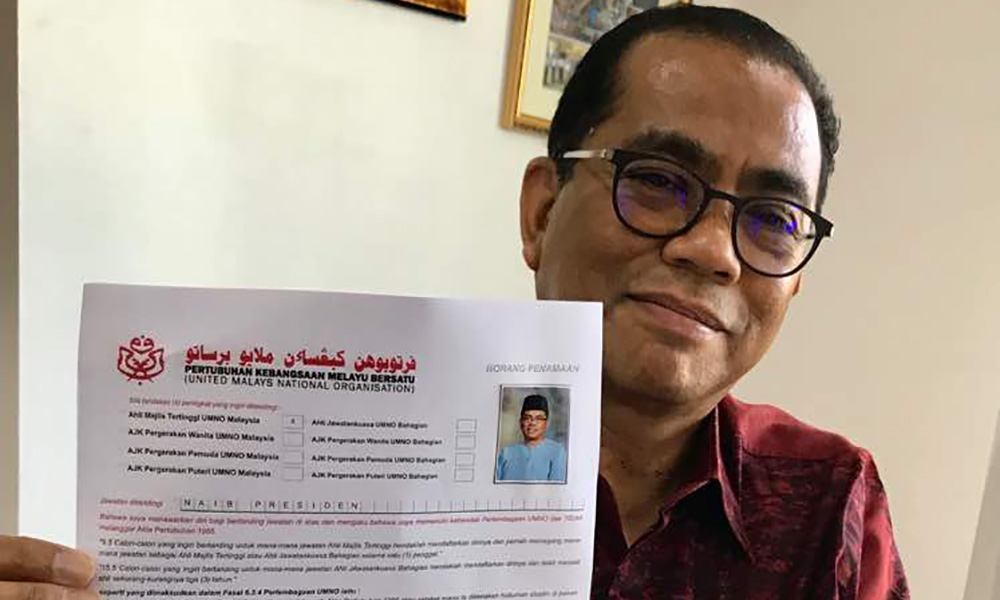

Khaled Nordin’s (photo) victory as vice-president is also illustrative, as he was most openly aligned to the Razaleigh camp and advocated for change in the party campaign, most obviously by repudiating money politics.

The challenge in this campaign was that given its brevity, the time to build clear alliances in the reform camp was limited. The reform movement, as a whole, lacked clear candidates as to who the reformers were at the supreme council, divisional and branch levels. These contests were largely about personality and personal loyalties rather than the direction of the party.

As such – despite the revolt within Umno for change – delegates had little choice in bringing about that change in the lower-level contests of the party to sustain the needed support to offset the institutional advantages and stranglehold of control that the “old” politics of Najib/Zahid maintain.

War within continues

The election, however, was only a battle, for the war inside Umno continues. There are three trends that are likely to continue.

The first is an exodus from the party. So far, three elected parliamentarians have left to become “independent”. This trend will continue, as Zahid does not have the confidence of large shares of the party. As many as half of the parliamentarians may leave, with even more at the state level.

It remains to be seen whether those leaving will form a different party, but the split inside Umno is real. Zahid’s victory is a defeat for the party, as it has meant that the party will not hold together. This could come in the form of large numbers leaving, resulting in a split or more gradual attrition and disengagement. Either path points to an erosion of support within the party itself.

Zahid’s victory has made Umno an even greater political target, as he not only perpetuates responsibility for the scandal of 1MDB in the party leadership, he brings his own scandals and baggage. Zahid is not popular by any measure among the general public. He is currently not able to command the respect of the voters, including a majority of Umno voters.

Zahid’s poor showing in the Umno presidential debate did little to bring respect to the party among the public and this trend will continue with Najib continuing to overshadow his proxy. Zahid – and Umno as large - will face the continued wrath of voters who demand accountability over 1MDB and further scandal revelations will bring even more contempt.

Losers are actually winners

Zahid’s visit to the MACC today will likely not be the first. He will not be alone in having to face questions about the finances and money within the party, as the election of the “old guard” makes the entire leadership more vulnerable. Najib’s claim that 1MDB was used to “help” the party and the cash in his apartment was actually Umno money – his practice of using the party for his own defence – is now haunting the party as a whole.

Ironically, many of the victors in the Umno polls are actually losers, with the losers actually winners. Khairy (photo, far left) and Razaleigh have both come out of the contest stronger than when they went in, standing up for change and advocating for a more hopeful alternative future for the party. Sadly, Najib’s continued hold over the party in alliance with many warlords and the debacle of his leadership has rained down further suffering on Umno.

The third trend is one where there will be efforts to survive the internal divisions and external censure. This will likely follow the same “old” playbook of Najib – denial and defensiveness, cash-and-carry politics, ratcheting up race and religious rhetoric and the use of underhanded undemocratic tactics.

Expect greater outreach to PAS under Zahid’s proxy leadership, with efforts to mobilise more conservative religious and racial forces. The election of non-reform aligned religiously conservative Umno Youth chief Dr Asyraf Wajdi Dusuki will likely further enhance this trajectory.

Sadly, this sort of approach (old politics with an even deeper conservative religious orientation) will only undermine Umno further as it cannot attest to any moral high ground with its current leaders. But the denial and insularity of many leaders in the party blind many inside to how destructive this path will be, both for Umno itself and Malaysia’s social fabric. Offers of defection and disturbing discourse are coming in a climate of desperation as those elected try to hold the party’s debilitation at bay.

Historically, splits in Umno, legal challenges for the party and defensive responses have been dangerous times in Malaysian politics. This time, however, Umno is in opposition and the dangers it faces are primarily self-destructive.

This does not mean that there will not be spillovers, creating greater political uncertainty in Malaysia, as new Malaysia still contends with forces of the past who are doing everything in their power to survive.

BRIDGET WELSH is an Associate Professor of Political Science at John Cabot University in Rome. She also continues to be a Senior Associate Research Fellow at National Taiwan University's Center for East Asia Democratic Studies and The Habibie Center, as well as a University Fellow of Charles Darwin University. Her latest book (with co-author Greg Lopez) is entitled ‘Regime Resilience in Malaysia and Singapore’. She can be reached at bridgetwelsh1@gmail.com. - Mkini

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.