The Unified Examination Certificate (UEC) has been a political hot potato in Malaysia for decades.

The UEC was mentioned in both the BN and Pakatan Harapanelection manifestoes for their 14th general election campaigns.

When Deputy Education Minister Teo Nie Ching said she aims to have the federal government confer official recognition for the examination by this year-end, she received brickbats from the likes of PAS and Angkatan Belia Islam Malaysia (Abim).

But what is the UEC? Is the criticism against it justified? In this instalment of KiniGuide, we’ll take a quick class on the UEC and the contentious issue of conferring it official recognition.

What is the UEC?

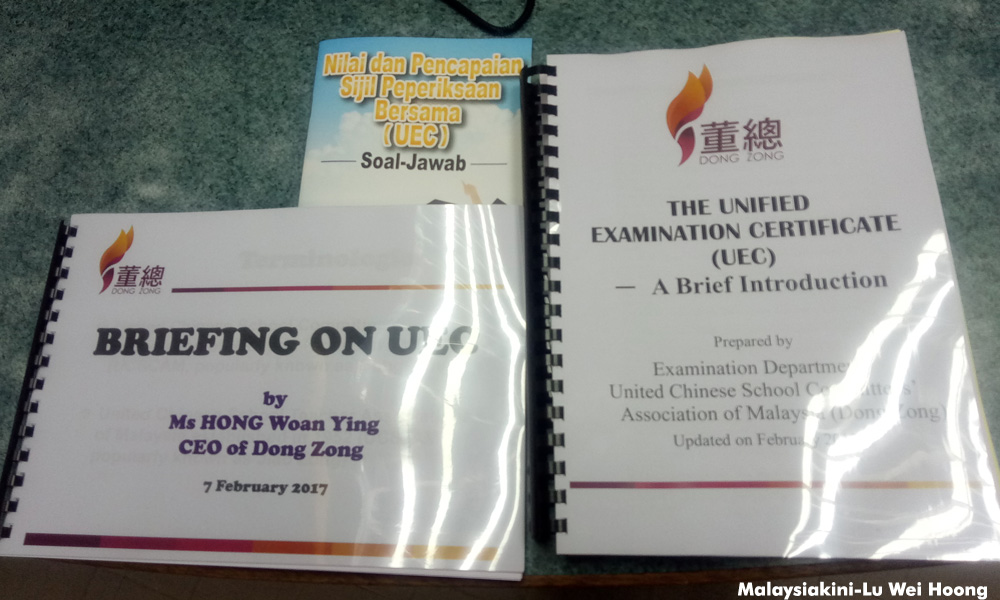

The UEC is a standardised test administered by the Malaysian Independent Chinese Secondary Schools Working Committee (MICSS) since 1975, which in turn is represented by members of the United Chinese School Committees' Association (Dong Zong) and United Chinese School Teachers' Association (Jiao Zong). The two associations are also jointly known as Dong Jiao Zong.

The joint committee offers the Junior Middle Level (UEC-JML) and the Senior Middle Level (UEC-SML) examinations, and as well as a vocational training certificate (UEC-V).

It also develops the curriculum for Chinese independent high schools.

These examinations are conducted in 60 Chinese independent high schools as part an education that lasts six years, though some schools also offer an additional year for students who want to prepare to sit for the STPM examination as a means to expand their opportunities for employment and further education.

According to Dong Zong’s website, there were 10,217 UEC candidates last year. For comparison, there were 43,042 STPM candidates that year.

The UEC-SML examinations for some non-language subjects such as Science subjects, Mathematics subjects, Commerce and Bookkeeping and Accounting are available in both English and Chinese, whereas other non-language subjects such as History and Economics are available in the Chinese language only.

UEC-JML examinations for non-language subjects are in Chinese, except in Sabah where Science and Mathematics are bilingual.

How did it get started?

It started with the passage of the Education Act 1961 that required schools to use either Bahasa Malaysia or English as the medium of instruction. Some Chinese vernacular secondary schools refused to abandon their mother tongue, and these became independent schools.

However, this newfound independence also meant that the government would no longer administer standardised tests at these schools.

Dong Zong states on its website: “From 1962 to 1974, there was not a specially established unified examination system for the Chinese secondary schools or Chinese independent high schools. Each school would hold its own graduation examinations and issue its own certificates of graduation.

“Some of the students would participate in the government public examinations, many of whom would transfer to national secondary schools or national-type secondary schools after obtaining passes for the exams. Others would further their studies at Nanyang University in Singapore or various universities in Taiwan using the certificates of graduation issued from their schools.

“Since the primary medium of instruction for Chinese independent high schools is Chinese, it is only natural that the necessity of having an examination in the Chinese language to assess the students’ standard of academic performance (especially Junior 3 and Senior 3 students). This need had not been fulfilled until the Malaysian Chinese Independent High School Unified Examination commenced in 1975.”

Wait, what about national-type schools? Don’t they use the Chinese language too?

National-type Chinese schools only use Chinese as the medium of instruction in primary schools (SJKC).

At the secondary school level (SMJK), Bahasa Malaysia is used as the medium of instruction instead. National-type primary and secondary schools also use the same syllabus as their national school counterparts, which is developed by the Ministry of Education.

The main difference between national secondary schools and national-type secondary schools in terms of its education is that the former devote more class time to teaching Chinese lessons.

This is the result of a compromise reached during the same reforms that led some Chinese vernacular schools to become independent schools.

Some other vernacular schools had opted to adopt the national syllabus in exchange for partial government funding, but also maintained some of its autonomy. These became the national-type schools that we know today.

In contrast, Chinese independent high schools use Chinese (and in some cases, bilingually alongside English) as the medium of instruction, and use a curriculum developed by MICSS instead of the Ministry of Education.

They also operate without government funding except for occasional grants, and manage their own affairs.

Who recognises the UEC?

According to a 2014 brochure published by Dong Jiao Zong, the UEC is recognised by 1,259 institutions of higher learning in 15 countries and territories worldwide, of which 820 are based in mainland China.

Other countries and territories include Singapore (11), Taiwan (162), the UK (38), Australia (35), Hong Kong (eight) and Indonesia (three).

In addition to these 15 countries, it said some UEC graduates have also managed to gain acceptance in Thailand, India, Macau, Italy, Germany and Russia.

In Malaysia, Dong Zong said there are 59 institutions of higher learning that recognise the UEC. All of these would have been private universities, since the UEC is not recognised by Malaysian public universities.

In universities where they are accepted, they are generally considered equivalent to the STPM or the UK’s GCE A-Level. Thus, they can be used for admission for certificate, foundation, diploma and bachelor’s degree programmes.

For public service entrance, the UEC is generally not recognised, apart from exceptions such as the state civil services of Malacca and Sarawak. In the Sarawak case, this in on condition that the candidate also passed the SPM Malay examination.

UEC holders are accepted in government teachers’ training colleges as well if they also have a credit in SPM Bahasa Malaysia, and a pass in SPM History and English subjects. Such graduates may only enrol in programmes that lead to a career in SJKC schools.

Why won’t the federal government recognise the UEC?

The previous BN-led administration addressed this issue in numerous public statements, including through written replies in the Dewan Rakyat.

In one such reply dated March 16, 2016, the Ministry of Higher Education said the cabinet had decided on Nov 6, 2015 that “the government could not recognise the UEC at this time because it is not based on the national curriculum and is not in line with the national education philosophy. This is the reality that has to be accepted because it is linked to national interests and sovereignty.”

The reply also said the Ministry of Education had given three reasons for the non-recognition, which are in line with the cabinet decision.

It said Malaysian independent Chinese secondary schools do not follow the national education policy, while the UEC examinations are not monitored by the Ministry of Education or any entity recognised by the government.

The curriculum used in the UEC is also not equivalent to national curriculum and examinations, it said.

The Ministry of Higher Education added that it has taken a similar stance as the Ministry of Education, and gave four reasons for the non-recognition.

Among others, it said the UEC Bahasa Melayu subject is not equivalent to its SPM counterpart, and the UEC did not have enough coverage on Malaysian history.

What other criticisms are there?

The issue of official recognition for the UEC has frequently drawn flak from various groups in the past, particularly from the right-wing nationalist groups.

These include allegations that such recognition would be detrimental to national unity and run counter to the Federal Constitution, particularly Article 152(1).

It is also alleged that its history curriculum is too China-centric and lacking in attention towards Malaysian history. According to Perkasa education bureau chief Abdul Raof Hussin (photo), the UEC ignored the philosophy and ideology of Malaysia’s nationalism, especially in the understanding of the Rukun Negara.

Abdul Raof also claimed that the UEC curriculum wrongly purports that Muslims pray six times a day by taking Friday prayers into consideration, and disputed its death toll for the racial riots of May 13, 1963.

Meanwhile, in an interview with Utusan Malaysia published on Nov 26, 2017, former National Education Advisory Council member Teo Kok Seong argued that the UEC should not be recognised to protect those who support the national education system.

Teo (photo) added that recognising the UEC would also result in pressure from other groups to push for recognition for other qualifications, such as the GCE A-Levels.

There are also other more outlandish claims made by various quarters about the UEC, including claims that the examination questions are set by foreigners or that its History subject completely lacked local content.

So are the criticisms justified?

Clearly, not all the criticisms have merit. While it is hard to gauge whether recognition for UEC would, in fact, undermine national unity, Article 152(1) Federal Constitution does not only state that the Malay Language shall be the national language.

Articles 152(1)(a) and 152(1)(b) make Article 152(1) conditional upon that “no person shall be prohibited or prevented from using (otherwise than for official purposes), or from teaching or learning, any other language”, and, “nothing in this clause shall prejudice the right of the federal government or of any state government to preserve and sustain the use and study of the language of any other community in the Federation.”

Hence, teaching with Chinese as the medium of instruction - even if it has the backing of the federal government - is not necessarily inconsistent with the Federal Constitution, especially since Bahasa Malaysia - as required by the Education Act 1996 - is a mandatory subject in Chinese independent secondary schools.

In addition, Section 18(3) of the National Education Act 1996 states that private schools are deemed to have complied with the national curriculum if a list of core subjects are taught in those schools.

Subjects listed as core subjects for the secondary level are: the national language (Bahasa Malaysia), English, Mathematics, Science, History, Islamic Education (for Muslim pupils), and Moral Education (for non-Muslim pupils).

What about the criticism of its curriculum?

As mentioned above, the UEC curriculum is developed in-house by the MICSS, rather than overseas. It also publishes its own textbooks.

As for its standard of Malay, then Dong Zong chairperson Vincent Lau (photo) reportedly told the Malay Mail last year that there may be differences between UEC Malay and SPM Malay subjects, the latter of which is a requirement for admission into local public universities.

However, Lau said, Dong Zong is amenable to having UEC students sit for the SPM Malay examinations if this means they won’t have to sit for the entire examination in addition to the UEC.

As for History lessons, he claimed that Chinese independent schools cover a wider scope of History lessons on the World, China, Malaysia and South-east Asia.

A check on the UEC-SML course outline reveals that it is divided into 43 chapters.

The first section of 12 chapters is about the history of Malaysia and the Southeast Asia region, of which nine chapters directly concern the history of Malaysia, beginning from the Malacca Sultanate.

Chinese history makes up another section totalling 16 chapters, while the final section of 15 chapters is on world history from the Italian Renaissance to post-Cold War developments.

Where do things stand now?

Despite pressure, Education Minister Maszlee Malik said yesterday that there will be no ‘flip-flop’ on Pakatan Harapan’s promise to allow UEC graduates to be admitted to public universities, provided that they obtain a credit in Bahasa Malaysia at the SPM level.

However, unlike Teo, Maszlee did not give any timeline for its implementation, only that it would not take as long as BN did.

He had said on Sunday that the government would not rush the matter, but instead conduct a study before delivering on Harapan’s promise.

“(Although) UEC (recognition) is among the promises made in Pakatan Harapan's manifesto, we need to take into account the views of various parties and (the interests) of Bahasa Melayu and national harmony. I will meet with various stakeholders, including those who champion the national language,” Maszlee said.

This instalment of KiniGuide is compiled by KOH JUN LIN.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.