After the events of this weekend – the threats to leave the coalition in the presidential council meeting, followed by Bersatu, Warisan and Azmin Ali’s PKR camp openly joining forces with Umno and PAS – the coalition government that was elected to federal power in 2018 is over.

E tu Bersatu?

Pakatan Harapan may reconfigure itself, go into opposition or go to the polls when (and if) new elections will be called - but indications are that it will be replaced with a new backdoor reconfiguration.

Cooperation among PAS, Umno, Bersatu and the split faction of Azmin – parties that align on issues of race and patronage – have been in the works for some time. Driven by the ‘get’ card – get out of jail, get back into position, get accounts unfrozen and most important of all ‘get into power’ – the elite machinations have been ongoing. Money and power are indeed powerful drivers.

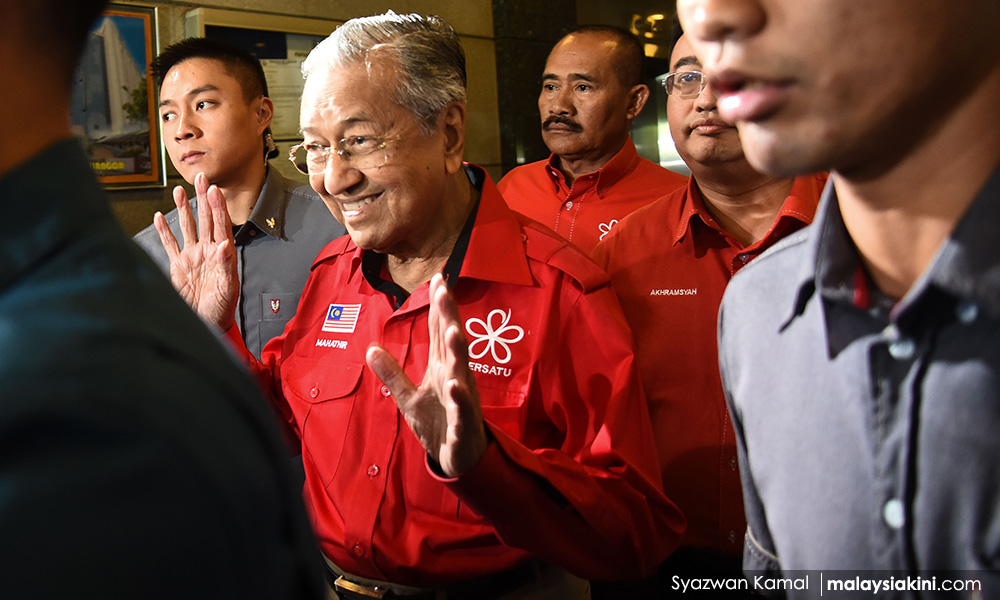

What changed in the last week was that the kingmakers – the elected elites in Sabah and Sarawak represented by Warisan and GPS formerly joined the Muafakat coalition, giving Dr Mahathir Mohamad and his now allies of Umno and PAS the numbers to form a majority government. Warisan had long been in the Mahathir camp, but GPS put aside its opposition to PAS to join the new Muafakat Nasional coalition. The East Malaysian parties have opted to be on the ‘winning’ side at the elite federal level.

The open threat to leave the coalition by Bersatu was a smokescreen, lulling other members in Hapan into a sense that the coalition would hold on. In fact, it had already split much earlier, as the divisions over leadership, racial politics and reform had split the coalition for some time. The more Anwar Ibrahim (below) pushed for a date of the transition, the more the forces opposed to his leadership worked to consolidate an alternative.

A new government will, in all likelihood be formed at the federal level, with new configurations across state governments. Non-Harapan governments will form in Kedah, Perak, Malacca, Johor, Negri Sembilan and Sabah. New ‘working’ relationships will be formed in Perlis, Pahang, Terengganu and Kelantan, although the dominant party will remain in charge. There will be uncertainty associated with the government of Selangor as the tussle inside PKR will not be immediately clearly resolved. Harapan will hold in Penang, while in Sarawak the GPS will maintain its position.

As of the writing of this piece, the main decision rests with Malaysia’s Yang di-Pertuan Agong, who has to decide whether to be part of this process or push for new elections.

A legal but undemocratic elite transition

This new coalition Muafakat does not represent the majority mandate of the 14th general election (GE14). Included in the new coalition are tainted individuals who were part of the former Umno government, the same individuals who were seen to have failed in leadership before 2018. As time passes, it will become clear what was given to them for their cooperation.

A perceived failure to respect the GE14 mandate will evoke strong reactions, as the perceived betrayals are two-fold: among the political actors within Harapan and to the voters themselves. The calls for new elections are already sounding, as this is the most democratic alternative.

The anger on the ground against the elites who have chosen to undemocratically ignore the public mandate is real. The decision to go this route sends a signal to the electorate that their voice is irrelevant, and this will not go down well as many Malaysians vested hope in a more democratic system. For now, this hope has evaporated. How the anger will be channelled and controlled remains unclear.

The level of support for the incoming opposition elites, Anwar and the core parties of Harapan – DAP, PKR and Amanah – is not the same as it was in GE14. Accommodation and compromise have eroded public confidence, as have the intense focus on holding power, rather than deliverables. Harapan will have a challenge winning back public support, but how the government transition has evolved, shrouded in betrayal and backdoor deals without public inputs, will evoke sentiments.

The push among the Muafakat elites will likely be to use the remaining time before elections have to be called to stay in office. They control the key institutions within the state apparatus. Elected representatives in Malaysia are not bound to any specific party or person. The elected elites can legally form new alliances and form a new coalition government. Coalition governments reconfigure regularly when they collapse.

What is happening in Malaysia is what happens elsewhere in coalition systems – new alliances, new partners – where elite-driven parties make the decisions. Mahathir has chosen to take Malaysia in a different direction in a legal manner. What makes this transition difficult for some to accept is that Mahathir relied on ‘change’ and ‘democracy’ for this legitimacy, and this is not evident.

New (and old) appeals of legitimacy

Without a public mandate, the Mahathir-led Muafakat coalition will justify itself along three grounds. It will tie itself to Mahathir, his leadership continuity. As such, appeals will be made on the grounds of stability. Mahathir and his allies are resting on the impression that there is support for his leadership. Given the record level of the unpopularity of the premier in recent months, this will be a gamble. Mahathir 3.0 remains a man in his nineties. Yet, Mahathir will be touted as a hero by the PAS and Umno grassroots.

Further appeals will be made along racial and religious grounds, as this new government will be framed as the ‘Malay unity’ or ‘protecting Malays’ coalition. The idea of ‘protecting the Malays’ has long served as a form of legitimation. An important element of this will be couched as protecting the faith. The Muafakat coalition will point to the inclusion of East Malaysia and minority representatives to claim inclusion. Minority representation in the new government will be minimal and not based on strong minority support. Nominally it will exist, however. The issue of different visions of representation of communities will be a serious challenge ahead.

Finally, the government will be legitimised on its legality, as other elites in the system will endorse this change. There are vested interests in making sure the new government takes hold, and the new opposition will have to decide whether to accept a peaceful transition, – as all indications so far are that this is the case. Meetings today will revolve around this. Offers may be extended to include others in the name of ‘unity.’

Broken trust

Stability, ‘Malay protection’ and legality will be difficult forms of legitimacy to accept for many Malaysians. The end of Harapan in government signals the end of a pluralist inclusive dream and meaningful reform, but these hopes have been dissipating for some time.

The path ahead will not be easy. The timing of this elite government transition could not be worse for Malaysia – with global economic uncertainty, the Covid-19 virus threat and more. Bersatu, Umno and PAS combined do not attract new investors. Malaysia’s economy remains tied to political leadership, which has been inwardly focused for some time. Building domestic and international confidence will not be easy. The focus ahead will be inward, as the new government will have to form.

There is also no guarantee of stability with the new Muafakat coalition, especially when the constraints on funds are real and personality divisions and different interests abound. There are a lot of kings and want-to-be-kings in the new Muafakat coalition. Attention will centre on serving interests at the elite level and eyes will remain on a further post-Mahathir political transition. Without new elections, the Muafakat coalition will have not only the problem of trust among its partners but with the public at large.

The events surrounding the collapse of the Harapan government show that trust, once broken, is not easy to repair.

BRIDGET WELSH is a Senior Research Associate at the Hu Feng Centre for East Asia Democratic Studies, a Senior Associate Fellow of The Habibie Centre, and a University Fellow of Charles Darwin University. She recently became an Honorary Research Associate of the University of Nottingham, Malaysia's Asia Research Institute (UNARI) based in Kuala Lumpur. - Mkini

No such thing as back door government.

ReplyDeletepls tune ur head.