KINIGUIDE | As public impatience grows with graft cases that seem to unravel in slow motion, the MACC’s proposal for a deferred prosecution agreement (DPA) mechanism has stirred fresh debate.

The anti-graft agency’s chief commissioner, Azam Baki, has publicly backed the idea, describing the DPA framework as one that should be advanced to avoid high-profile cases becoming mired in years-long proceedings, which drain public funds.

Malaysiakini looks at what exactly a DPA is, and whether it risks becoming yet another pathway to impunity for the well-connected.

What is a DPA?

A DPA is a legal mechanism that allows prosecutors to suspend criminal proceedings against an accused party, typically a company, provided it agrees to fulfil certain requirements within a specific period.

Such conditions usually include paying financial penalties, returning misappropriated funds, cooperating with investigations, and implementing reforms to prevent future wrongdoings.

Under a DPA, charges are filed, but not immediately pursued. If an accused adheres to the prescribed stipulations, the prosecution is deferred and may ultimately be withdrawn.

However, if the agreed-upon terms are breached, prosecutors retain the right to revive the case and go for a trial. In instances where prosecutors proceed to trial, a conviction could lead to imprisonment terms, fines, and other punishments where applicable based on legislation used to frame charges.

DPAs are generally designed for corporate offenders, and in many countries, are subject to some form of judicial oversight to ensure the terms are fair, proportionate, and in the public interest.

Who uses DPAs?

DPAs are commonly used in jurisdictions such as the United States and the United Kingdom, where they now form part of the legal framework for tackling complex corporate crimes, including corruption, fraud, and money laundering.

In the US, however, DPAs were originally conceived as a way to help small, first-time offenders - often individuals or low-risk entities - get a second chance via an opportunity to avoid the long-term consequences of a criminal conviction.

The emphasis then was on rehabilitation rather than punishment, allowing prosecutors to conserve resources while encouraging corrective behaviour through court-imposed conditions.

The UK adopted DPAs in February 2014, with the mechanism aimed at encouraging companies to self-report criminal wrongdoing and tackle fraud, bribery, and economic crime.

Unlike the US model, for a DPA to have legal effect in the UK, the agreement must receive judicial approval at multiple stages, with judges assessing whether the deal is in the interests of justice with fair, reasonable, and proportionate terms.

Approved DPAs are also made public, a transparency measure intended to mitigate concerns that the mechanism could be abused.

What is Malaysia’s plan with DPAs?

Earlier this week, Azam told a Berita Harian podcast that the MACC has proposed a DPA mechanism as part of efforts to resolve high-value corruption cases involving RM100 million and above without full court trials.

The framework is expected to be tabled in the Dewan Rakyat in June, with the matter in the drafting stage following discussions with the Attorney-General’s Chambers (AGC).

The proposal would be applicable for corporate entities and individuals involved in corruption cases featuring values deemed as “extremely large”, the New Straits Times quoted Azam as saying.

“If we continue to worry solely about perception, when will we ever resolve these issues? It is our responsibility to convince MPs when the DPA is tabled,” he reportedly affirmed.

Noting that those accused could settle their cases through negotiated penalties and remedial actions, he added that a key advantage of the DPA is a clause on compensation to victims.

The nation’s top anti-graft officer pointed out that if DPAs were practised in the nation during the 2019 Sungai Kim Kim pollution incident in Pasir Gudang, Johor, the company could have been made to pay penalties, bear the cost of river cleanups, and compensate residents.

The incident, which affected the health of over 2,000 people and resulted in the closure of 111 schools in the area, saw P Tech Resources Sdn Bhd being fined a total of RM640,000 in June 2024.

The company faced eight counts of pollution-linked charges under the Environmental Quality (Clean Air) Regulations 2014. Lorry driver N Maridass was also hit with a maximum fine of RM100,000 for causing pollution by illegally dumping scheduled waste into the river.

Certain quarters, however, noted that the penalties came well after the damage was done, and did little to address the immediate costs to environmental cleanup, public health responses, and compensation for affected residents.

Residents have since resorted to legal action against 12 defendants, including Putrajaya and the Johor state government, in a bid to secure financial remedies for health problems, losses, and distress suffered due to the pollution.

Why does MACC want DPAs now?

MACC’s push for DPAs comes amid mounting frustration over the perceived slow pace in prosecuting high-value corruption cases, with probes involving large corporations, layered transactions, and multiple jurisdictions often taking years to conclude.

Such cases are also frequently delayed by procedural challenges, evidentiary hurdles, and protracted trials.

As proceedings drag on, the cost to the state mounts, while the prospects of securing timely convictions or recovering misappropriated assets diminish.

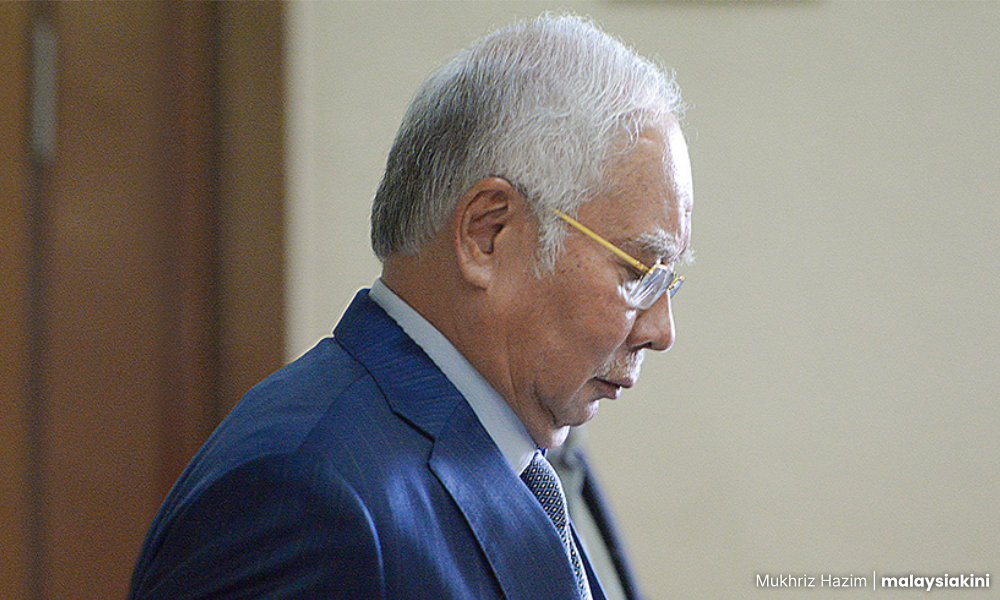

One example is how former prime minister Najib Abdul Razak was charged in September 2018 in his RM2.3 billion 1MDB trial. The prosecution took nearly five years to close its case, while the defence stage took another year.

It was only on Dec 26 last year that a verdict was delivered, and Najib was sentenced to 15 years’ jail and a RM11.38 billion fine.

Najib can also bring his case to the Court of Appeal and the Federal Court, potentially extending the litigation process by several more years before finality is reached.

MACC’s approach with DPAs also reflects a shift towards prioritising asset recovery over convictions alone, on the basis that returning stolen funds to the public purse may better serve the public interest than pursuing trials with uncertain outcomes.

What was the reaction to Azam’s announcement?

The Center to Combat Corruption and Cronyism (C4 Center), however, was quick to lambast the proposal, particularly Azam’s suggestion that DPAs be extended to individuals.

The NGO argued that the mechanism would effectively encourage leaders to commit massive amounts of corruption to qualify for a DPA, questioning the logic behind removing “true accountability” for the most serious offenders.

The group further cautioned that DPAs could potentially enable powerful individuals to pilfer public coffers and escape only by paying restitution.

It also asserted that the MACC’s proposal represented an "extremely dangerous" misunderstanding of DPAs, which it said should be limited to legal persons and not natural persons.

"If Putrajaya intends to introduce a DPA scheme, the fundamental consideration is, why should an entity involved in criminal activity be afforded the opportunity for non-trial resolution?” C4 Center asked.

It also urged the government to publicly commit to restricting DPAs to corporate entities and ensure that non-conviction-based asset forfeiture is not solely used to settle cases and recoup financial losses, while avoiding efforts to bring those involved in corrupt activity to justice. - Mkini

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.