Politicians from Sarawak and Sabah are pressing for one-third of parliamentary seats, up from a quarter currently. This is not a demand for equal representation, but greater over-representation, because East Malaysian voters constitute only one-sixth of the nation’s total.

Why do Sarawak and Sabah want greater malapportionment at the expense of Malayan states?

In his latest call, Sarawak Chief Minister Abang Johari Openg (above) said: "Sabah and Sarawak are supposed to maintain one-third out of the 222 seats (after Singapore left Malaysia). If not, the power distribution in Parliament will be solely relying on Peninsular Malaysia".

This can be unpacked into two parts. First, history, ie, it’s the entitlement of Sarawak and Sabah promised in the formation of Malaysia. Second, check and balance, ie, East Malaysia needs veto power to prevent Malaya’s bulldozing of constitutional amendments.

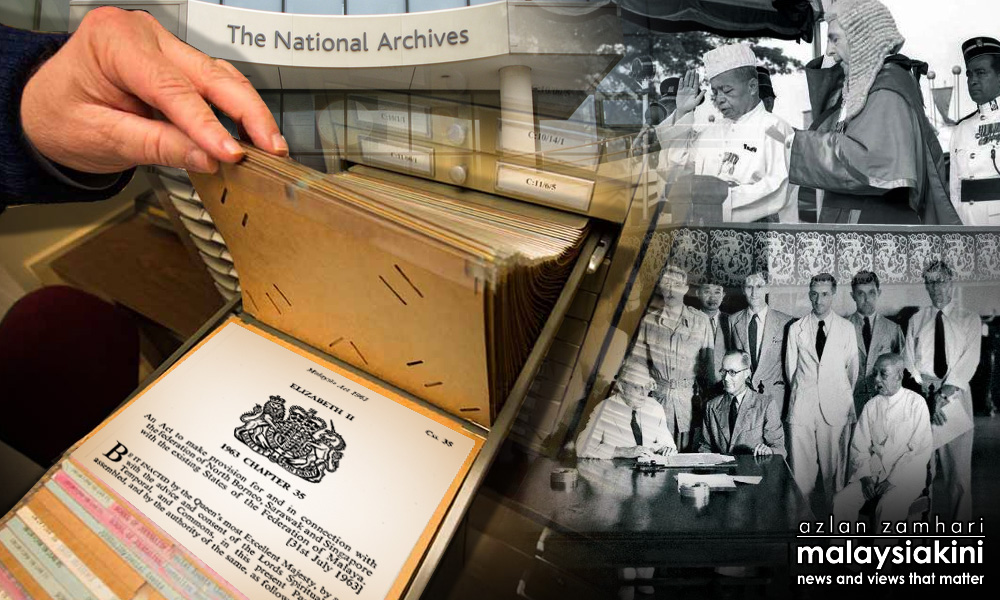

Was it promised in MA63?

Many Sarawak and Sabah friends would go further to claim that this is grounded in the Malaysia Agreement 1963 (MA63).

The grand version of the history and check-and-balance argument goes like this:

- When Malaysia was formed in 1963, Sarawak, Sabah and Singapore combined were given 55 seats in the 159-member federal Parliament (34.6 percent), meant to prevent Malaya’s unilateral moves to amend the Federal Constitution and disadvantage the three states.

- After Singapore left Malaysia in 1965, Sarawak and Sabah should inherit Singapore’s 15 seats to retain the veto bloc against Malaya’s dominance.

But is this a historical fact or myth?

Sadly, I cannot find anything in the MA63 that supports this claim. I stand corrected and welcome any wise women and men to show me the opposite.

Going beyond MA63, I, however, do find a promise concerning parliamentary seats in the 1962 Intergovernmental Committee (IGC) report.

Consisting of representatives from Malaya, Singapore, North Borneo (later renamed Sabah) and Sarawak governments, IGC made many recommendations that were adopted by MA63.

Here is what appears under Paragraph 19(2):

“Article 46(1) should be amended to increase the numbers of the House of Representatives from one hundred and four to one hundred and fifty-nine (including the fifteen proposed for Singapore). Of the additional members, sixteen should be elected in North Borneo and twenty-four in Sarawak. The proportion that the number of seats allocated respectively to Sarawak and to North Borneo bears to the total number of seats in the House should not be reduced (except by reason of the granting of seats to any other new State) during a period of seven years after Malaysia Day without the concurrence of the Government of the State concerned, and thereafter (except as aforesaid) shall be subject to Article 159(3) of the existing Federal Constitution (which requires bills making amendments to the Constitution to be supported in each House of Parliament by the votes of not less than two-thirds of the total number of members of that House)."

Two facts are crystal clear: first, Singapore was never lumped together with Sabah (North Borneo) and Sarawak in seat allocation, hence the proportion guaranteed was only “North Borneo’s 16” + “Sarawak’s 24” divided by “Malaysia’s 159”, ie, 40/159 or 25.16 percent; second, this 25.16 percent proportion was protected for only seven years after Malaysia Day. Hence, the quarter proportion had expired after Sept 16, 1970, and its continued adherence for most of the time after 1970 was driven by political goodwill, not by legal obligation.

What about check and balance?

Now, if Sabah and Sarawak were not promised one-third of seats, can they make that case on the ground of check and balance?

The answer: yes and no.

Yes, because constitutional veto power may be justified in many circumstances, especially in a federation.

No, because such veto power in a federal system is normally vested in the Upper House, not the Lower House.

The Lower House is to represent the majority’s will and hence must be based on “one person, one vote, one value” principle. Because democracy is premised on political equality, this is especially true in parliamentary systems where the Lower House indirectly chooses the government.

In contrast, the Upper House is to protect minority or special interests. It is to prevent the tyranny of the majority, like what Abang Johari has alluded to.

So, it is common in federations to see small states over-represented in the Upper House. In the US, large states like Texas and tiny states like Rhode Island all have two seats in the Senate.

Using a car as a metaphor, the Lower House acts as the fuel pedal to drive things, while the Upper House functions like the brake pedal to force a rethink.

If check and balance are what Sabah and Sarawak, they should push for an elected and empowered Senate where the two states have one-third of seats. Shouldn’t they?

East Malaysian MPs – who are their bosses?

The argument that Sabah and Sarawak’s interests will be better protected if they have more MPs in the Parliament is based on one assumption: the bosses of East Malaysian MPs are East Malaysian voters.

Has this been true?

On Sept 19, 1966, after the Emergency Proclamation in Sarawak, the Parliament voted to amend Sarawak’s State Constitution so that chief minister Stephen Kalong Ningkan, hated by Kuala Lumpur, could be removed. All 15 Malayan opposition parliamentarians opposed and walked out in protest. Out of Sarawak and Sabah’s 40 MPs, only eight of them – four from Ningkan’s SNAP and four from SUPP (then a principled opposition) – did the same.

Ten years later, on July 13, 1976, the Parliament infamously amended Article 1(2) to downgrade Sabah and Sarawak from a separate category of “Borneo States” to two of 13. The bill was carried by 130 out of 154 MPs, including 22 out of the 24 from Sarawak and 11 out of 16 from Sabah. Did the remaining seven Borneo parliamentarians vote against? No, they were simply missing in action.

Twice, in 1966 and 1976, most Sarawak and Sabah parliamentarians voted to undermine their own states, like a turkey voting for Christmas.

In the Malayan court, Sarawak and Sabah MPs were not even kingmakers, but simply the king’s men. In their state capitals, Mustapha Harun, Taib Mahmud and most recently, Musa Aman, were given a free hand to plunder their own states in exchange for their support for Kuala Lumpur.

Three paths to empower Sabah and Sarawak

There are three paths where Sabah and Sarawak can be empowered in the Federation of Malaysia. Why is everyone only focusing on the increase of parliamentary seats?

Yes, we know that is the path to more posts as ministers, special envoys, deputy ministers and GLC chiefs, and now, even PM or DPM.

But why can’t you also pursue two other alternatives that will empower Sabah and Sarawak further?

The second path is the senatorial reform. Currently, our Dewan Negara is dominated by 54 (63 percent) federal appointees and decorated by 26 (37 percent) state representatives.

Its veto power is also laughable – delaying a financial bill passed by the Dewan Rakyat by a month and all other bills by a year. Even if Dewan Rakyat wants to abolish Dewan Negara, the latter can only delay its own death by a year. Because it is unelected, it deserves no greater power.

So, the needed reform is straightforward: an entirely elected Senate, with one-third of seats for Sabah (including Labuan) and Sarawak, and with power to reject and not just delay bills from Dewan Rakyat.

The third path is the devolution of power, not just from Kuala Lumpur to Kuching and Kota Kinabalu, but also from the state capitals to the 11 and five divisions in Sarawak and Sabah.

Here, Sarawak and Sabah politicians can learn from Singapore’s playbook in the negotiation for Malaysia.

In 1963, Singapore had a population larger than Sarawak and Sabah combined but it got only 15 parliamentary seats, much less than Sarawak’s 24 and Sabah’s 16.

Knowing Umno’s fear for PAP’s threat, Lee Kuan Yew astutely accepted under-representation in the federal capital in exchange for greater autonomy at home. In 1963-5, Singapore controlled its own education, medicine and labour policies, powers that Sarawak and Sabah never had.

Instead of being kingmakers or king’s men in Kuala Lumpur, Lee wanted Singapore to be king in their own state.

If Sabah and Sarawak see themselves as the equivalent of Malaya as a whole, and not its 11 states, then they should really treat their divisions as states with elected governments and demand devolution from the federal to divisions.

Lest they forget. Perak, Baram-Trusan (Sarawak’s fourth division) and Sandakan were once of the same rank as administrative units, with Resident as the highest colonial administrator.

In clamouring for greater over-representation, sorry, I see no resemblance of Borneo’s Lee Kuan Yew, but only the looming shadow of Taib Mahmud.

WONG CHIN HUAT is an Essex-trained political scientist working on political institutions and group conflicts. He currently leads the clusters on the electoral system and constituency delimitation in the government’s Electoral Reform Committee (ERC). Mindful of humans’ self-interest motivation while pursuing a better world, he is a principled opportunist. - Mkini

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.