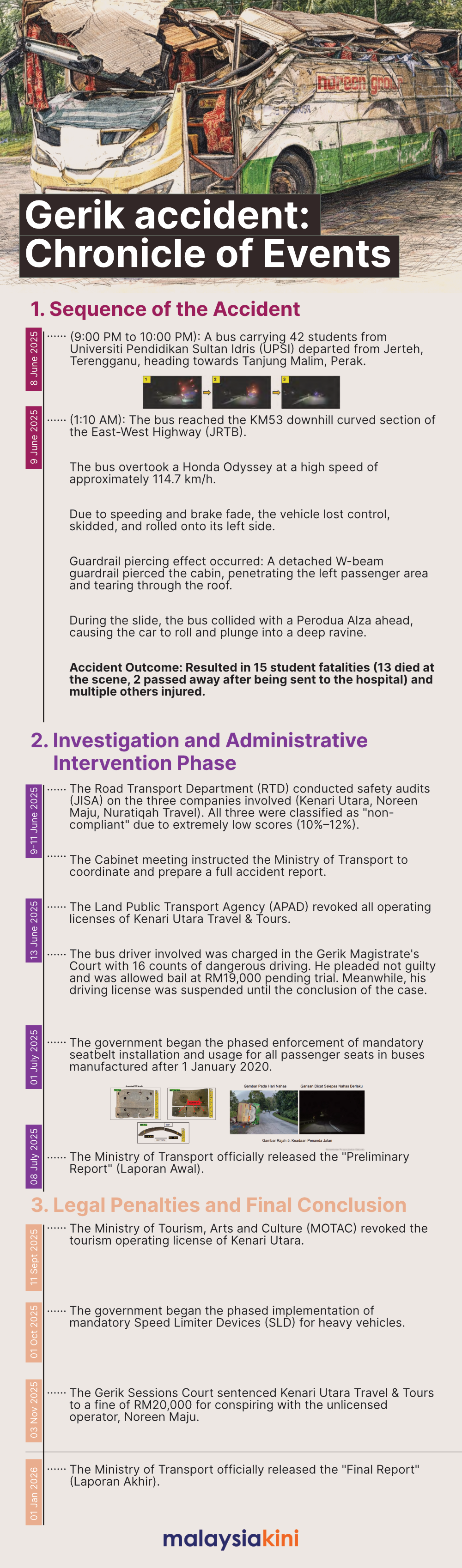

In the early hours of June 9 last year, a tragic accident on the East-West Highway claimed the lives of 15 students.

Last Friday, a special task force appointed by the Transport Ministry released its findings on the crash.

This Malaysiakini report focuses on the official accountability section of the investigation, highlighting two critical issues: infrastructural defects and systemic regulatory failures.

The emphasis is deliberate. Public discourse has long tended to “concentrate responsibility downwards while blurring oversight upwards”.

In practice, this means the driver and the companies involved have been subjected to microscopic scrutiny, while the public sector’s administrative accountability has remained superficial.

Such an imbalanced focus fosters a dangerous illusion: that road safety improves simply by catching “bad drivers” and penalising “bad companies,” and that government accountability is fulfilled merely through enforcement and policy announcements.

This article does not seek to absolve the driver or the bus company. Its purpose is to correct a persistent bias in public debate, shining a light on the institutional responsibilities of the public sector that are too often overlooked.

From ‘international standards’ to ‘fatal defects’

Two days after the accident, Malaysia Gazette reported Works Minister Alexander Nanta Linggi publicly defending the Public Works Department (PWD), claiming that the guardrails at the scene fully met “international safety standards” and had functioned to save lives by preventing the bus from plunging into a deep ravine.

He denied claims on social media that the “guardrails were useless”, emphasising that such claims were “groundless” and misleading to the public.

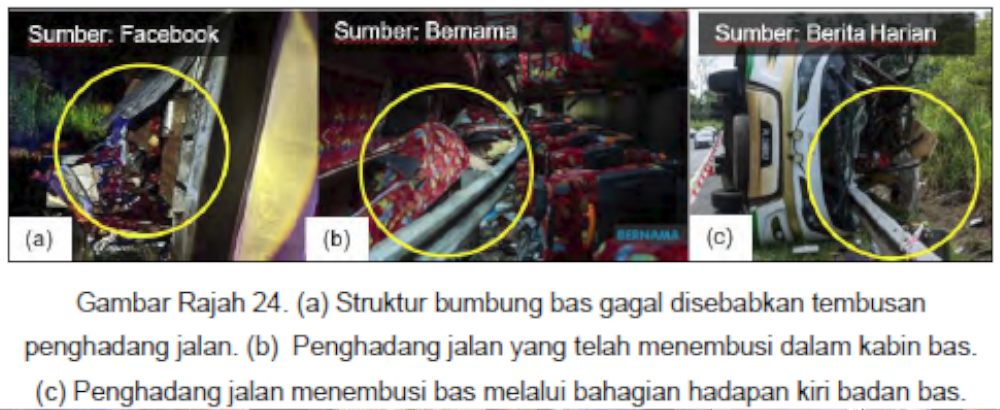

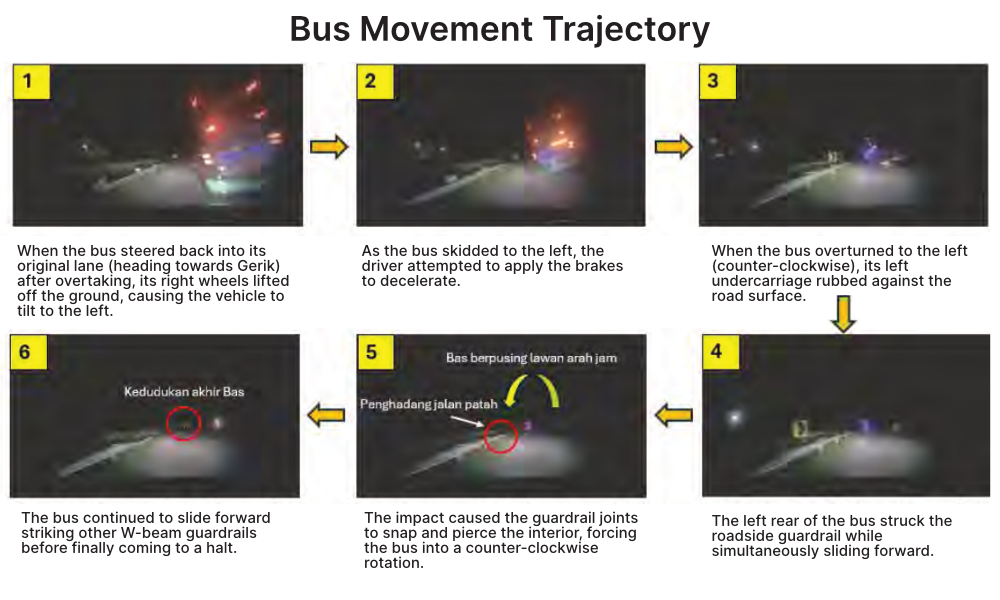

However, the investigation report tells a different story, pointing out that the guardrail not only failed to perform its intended function but was actually the “primary mechanism” (mekanisma utama) that exacerbated the severity of the accident.

“The guardrail penetrated the bus cabin, determined as the primary mechanism that aggravated the severity of passenger casualties,” read the report.

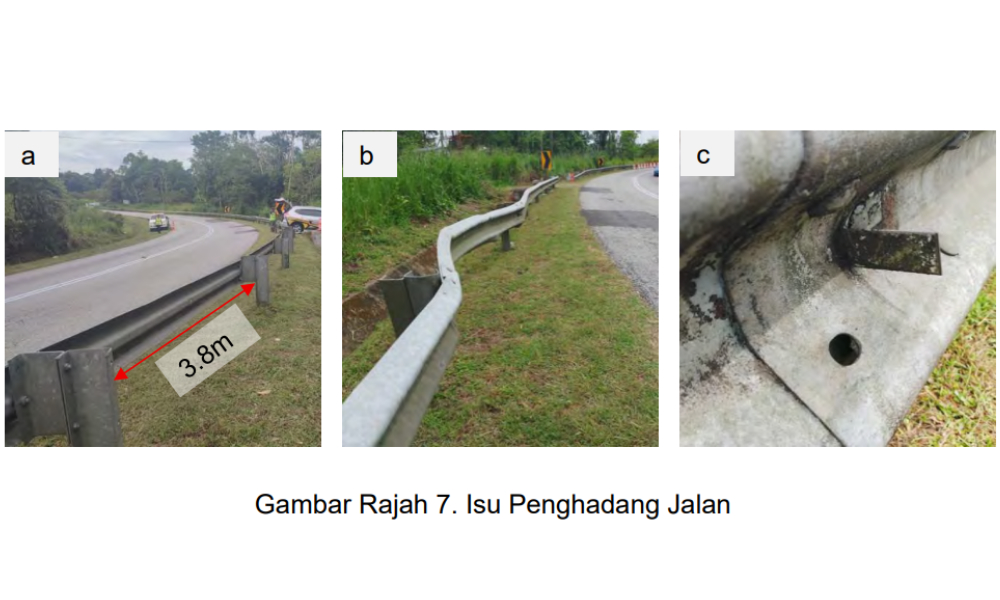

The report noted that the structure of the “W-beam” guardrail on the segment of the road where the accident occurred contained serious hidden dangers, such as:

Non-compliant installation: The spacing between guardrail posts was 3.8m, far exceeding the 2m limit for TL-3 (Test Level 3) standards, which severely weakened the structural strength.

Assembly errors: The splices of the guardrail panels were actually installed against the flow of traffic, and multiple bolts were missing. This resulted in the guardrail snapping and peeling away upon impact instead of absorbing energy.

Failure of end terminal design: The end terminal detached, and no “geometric flare” was implemented during installation, causing it to become a blunt point and increasing the risk of piercing.

Insufficient safety rating: Only “TL-2” level guardrails were used on that particular stretch of road, which are inadequate for intercepting heavy vehicles like buses.

The report further noted that these maintenance and design defects turned the guardrail into a “spear” during the accident, directly piercing the left side of the bus and increasing the death toll, particularly among passengers on the left side.

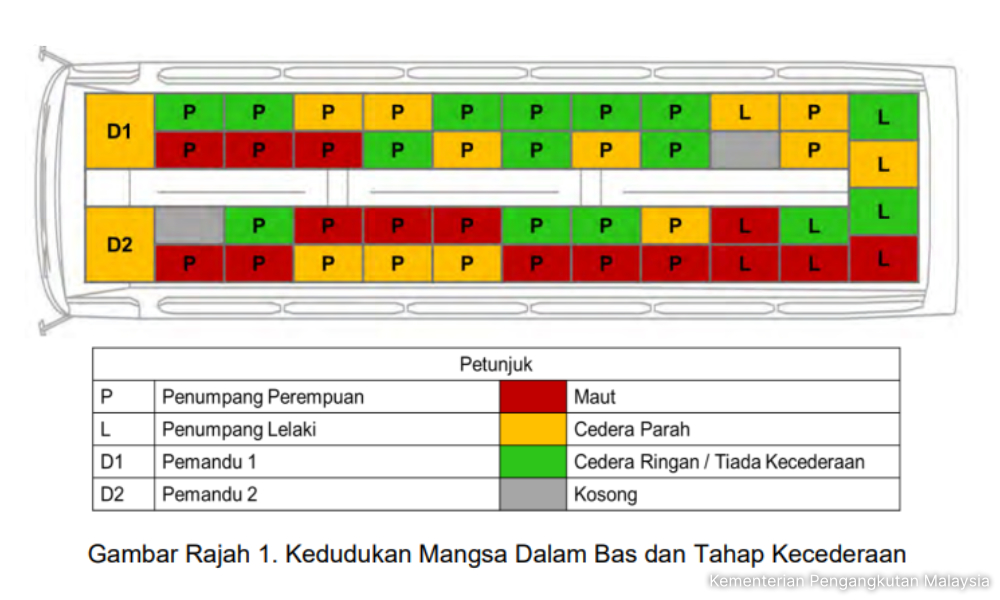

Of the 15 deceased students, 11 were seated on the left side of the bus at the time of the accident.

“Most of the deceased were located on the left side of the bus, which was the primary impact zone and the path of the guardrail penetration,” the report noted.

The report also stated that the force of the impact caused several sections of the W-beam guardrail to penetrate the bus body, severely damaging the vehicle’s pillars and roof, which in turn aggravated passenger injuries and reduced the “survival space”.

The impact also caused parts of the bus roof structure to detach, resulting in several passengers being thrown out of the vehicle.

Poor road maintenance detected

The works minister had pointed out at the end of last July that, according to the latest 2024 traffic census, the lane involved was still at a good service level and was sufficient to handle existing traffic volume.

“Physically, the JRTB ( East-West Highway) is in good condition and safe for use.”

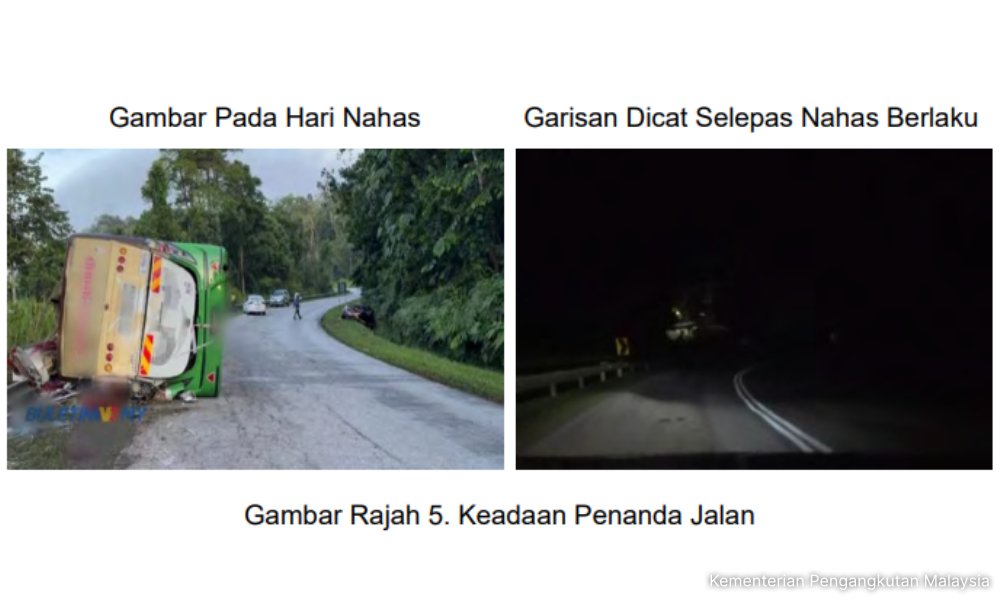

However, the report had a different assessment of the road conditions at the scene. It pointed out “alligator cracking” on the surface at the accident site, and noted that road markings were blurred due to wear and tear.

The report further noted that visibility issues were even more severe at night.

“Due to dirt and a lack of maintenance, the reflectors on the W-beam guardrails failed to function properly.

“Furthermore, no retroreflective road markings such as road studs or delineator posts were installed at the scene, making it difficult for drivers to identify lane boundaries and curves.

“As there were no streetlights installed, the environment was dark, making it difficult for drivers to detect hazards in advance,” it read.

The report concluded that these deficiencies in infrastructure maintenance severely impaired the driver’s judgement in complex terrain at night.

Additionally, the report pointed out that the road segment was curved and the driver’s line of sight was obstructed.

“According to design standards, the required stopping sight distance is approximately 490 meters. However, site inspections showed that even at a distance of 300 meters, the curve could not be clearly seen.

“Insufficient sight distance increases the risk of head-on collisions, especially when heavy or high-speed vehicles attempt to overtake,” it added.

Brake failure: Personal negligence, inspection limitations

The day after the accident, the 39-year-old bus driver, Amirul Fadhil Zulkifle, claimed that the cause of the crash was a brake malfunction, which led to him losing control of the bus and hitting the roadside guardrail.

“The bus was in good condition at the start of the journey; however, suddenly, when passing the elephant crossing bridge in Gerik, the brakes did not work, and the gears could not be shifted,” he claimed.

However, the police warned Amirul not to make public statements that could cause public speculation and affect the investigation.

The Straits Times also reported that Transport Minister Anthony Loke also warned Amirul not to spread unverified claims of “brake failure” to cover up “reckless driving”.

The investigation report stated that there was indeed a brake failure issue, but it was not the “sudden” failure the driver claimed; rather, it was a gradual brake fade.

The malfunction of the braking system was the primary cause of the bus losing control and the subsequent fatal crash.

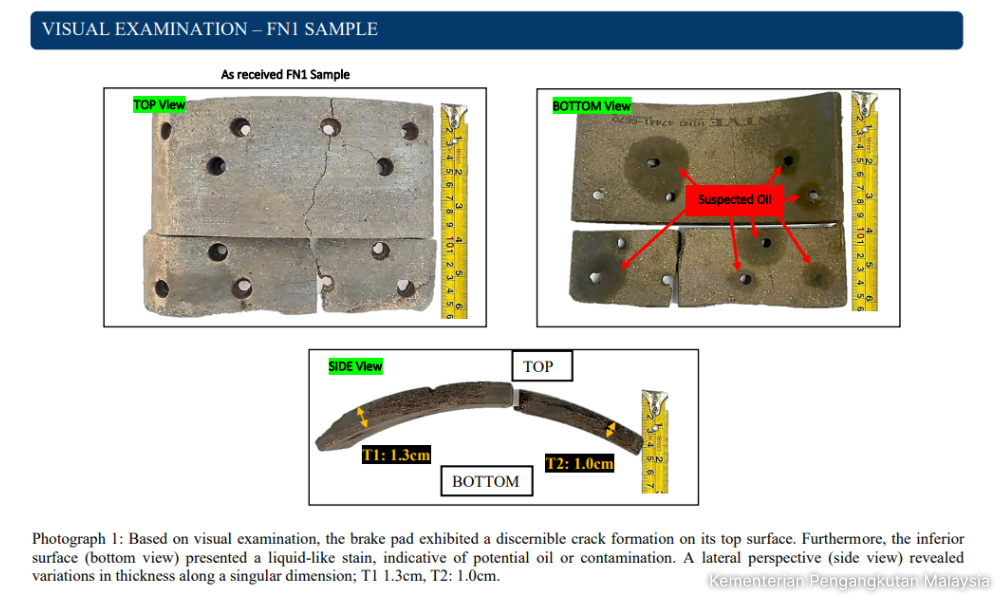

In explaining the causes of brake fade, the report not only pointed to the driver’s continuous and heavy braking on the downhill stretch but also mentioned deficiencies in maintenance and oversight.

The report noted that according to records, the ill-fated bus had undergone brake maintenance on Feb 9, four months before the accident, and had passed an inspection by the Computerised Vehicle Inspection Centre (Puspakom) on April 13, about two months before the crash.

It passed the brake efficiency test with a total score of 59 percent, meeting the minimum requirements of existing regulations.

However, the report highlighted the limitations of these official inspections.

The investigation found that before the accident, critical repairs to the brakes and wheel hubs were carried out by an unauthorised and unregistered workshop.

In this regulatory vacuum, inferior semi-metallic materials that did not meet original equipment manufacturer (OEM) specifications were used, and the issue of grease leakage from wheel hub bearings contaminating the brake pads was not detected.

The report also cautioned that complying with maintenance standards and passing a static Puspakom test does not necessarily reflect the effective operating capability of the braking system under actual running conditions.

“Puspakom tests are conducted in a controlled environment over a short period; they are not designed to evaluate brake performance under continuous use, long-term heat accumulation, or when brake pad surfaces are contaminated by foreign substances,” it stated.

Administrative regulatory failure: Major systemic loopholes

After the crash, the mainstream narrative logic attributed the problem to “individual cases”, focusing on the driver and the company, such as the number of unpaid fines by the driver or company violations (leasing commercial vehicle licences).

The report revealed that the accident involved three companies: Kenari Utara, Noreen Maju, and Nuratiqah Travel & Tours. Among them, Kenari Utara violated regulations by leasing out its permit, Noreen Maju was the actual operator using the leased permit illegally, and Nuratiqah Travel & Tours acted as a cover.

However, the final report stated directly that regulatory agencies, such as the Land Public Transport Agency (Apad), the Road Transport Department (RTD), and the Tourism, Arts and Culture Ministry, also bear responsibility.

The report pointed out that while technical failure of the braking system, reckless driving patterns, and a lack of driver discipline management were key causes, they reflected deeper weaknesses at the organisational level and within safety management systems.

“This accident investigation reveals major systemic loopholes in the governance, regulatory compliance, and enforcement efficiency of tourism vehicle operators.

“The interplay between operators’ operational practices, violations of licensing regulations, and weak institutional oversight reflects a significant gap in the industry’s safety system.

“Firstly, the leasing of commercial vehicle licences by unlicensed parties creates operational safety risks and reflects weaknesses in licensing enforcement,” it stated.

The report noted that statistics show that although enforcement actions by Apad increased significantly - from 99 cases in 2022 to 441 cases in 2024 - its enforcement remains reactive, typically only occurring after complaints are received or accidents happen.

“Regarding the RTD, a shortage of manpower and logistics, combined with incomplete integration of information systems, makes continuous field supervision difficult and hinders the early detection of licence abuse and illegal operations,” the report stated.

Furthermore, the report pointed out a major flaw in the Tourism, Arts and Culture Ministry’s “Tourism Authorisation and Licensing System” (Tourlist) - the system that allows operators to apply for tour bus guide exemptions - which allowed Nuratiqah Travel & Tours to exploit a loophole.

The system employs an automatic approval mechanism when processing applications, without real-time cross-verification against the RTD or Apad databases.

“A check of Tourlist found that the company (Nuratiqah Travel & Tours) submitted an unusually high number of exemption applications during 2025, including 27 in January and 29 in February,” the report pointed out.

“This application pattern suggests a high probability that the exemption mechanism was abused, including license leasing or manipulation of the system by unlicensed operators.

“Furthermore, the driver’s details for the bus journey on the day of the accident did not match the actual driver involved, indicating weaknesses in physical verification and information control,” it added.

The report stated that Tourlist left space for illegal operational permits and highlighted weaknesses in digital regulation.

Where does accountability end?

The 188-page final investigation report pieces together a more complete structural picture of the tragedy that claimed 15 innocent lives: from driver operational errors and company disregard for safety to loopholes in the licensing system being exploited, and finally to road infrastructure defects, maintenance omissions, and regulatory failure.

These loopholes overlapped, pushing the risk toward an irreversible tipping point.

The report pointed out that the issue was never the fault of a single entity, but rather systemic defects running through multiple agencies, various regulations, and multi-layered decision-making chains.

These are deep-seated problems that have accumulated over time, been long ignored, and for a long time, were not treated as public safety hazards.

Regrettably, however, to date, only the driver and companies involved have faced specific punishments, such as fines, licence revocations, and criminal charges.

In contrast, no government departments or responsible officials within the regulatory chain have been held accountable; there are only “recommendations”.

The final investigation report emphasised that their findings and recommendations “aim to prevent a recurrence of similar incidents, strengthen the road traffic safety system, and safeguard the lives and well-being of road users”.

“Implementing the recommended safety measures will help address the identified weaknesses, strengthen the compliance framework, and plug enforcement loopholes.

“In view of this, all stakeholders are called upon to prioritise safety factors and actively cooperate to execute the necessary corrective actions,” it added.

Yet, in a situation where there is no accountability, a question lingers: if no one is required to take responsibility for institutional dereliction of duty, what basis do government agencies have to demonstrate a genuine will for reform?

- Mkini

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.