One hundred appears to be a magic number. From schools to workplace, students and employees alike are either asked to get 100 marks - a perfect score - or deliver a 100 percent performance each day.

In politics, the most famous example of the Hundred Days’ Reform involved Kang Yu Wei, the last Manchu reformer. The Manchu, otherwise known as the Ching Dynasty, for the lack of better word, was in a deep creek in 1898. Nothing they did ever work.

First, they lost to Britain in the Opium War in 1832, which forced Hong Kong to be ceded to the British rule. Then they lost more wars to the British which forced China to surrender Kowloon. When faced with the might of Portugal, it lost Macau too.

By the mid-19th century, the Manchu Dynasty had to contend with a rebel cum peasant called Hong XiGuan who was the leader of the Taiping Revolution. Hong, interestingly, saw himself as the second saviour after Jesus Christ, after encountering some missionary literature.

While not all his Chinese followers were Christians, Hong raised a huge army, comprising close to a million farmers, with pitches and forks, indeed axes and knives, to call for the overthrow of the Manchu Dynasty; a cause that was not unlike remnants of the earlier Ming Dynasty rebellions too.

The latter wanted the Manchus to be forced back to the northeast of China. Manchus, as the Ming loyalists reasoned, were not of Han origins or tribes. The Manchus were the usurpers of the throne of the Ming Dynasty.

By 1898, the Manchu Dynasty received another slap: they lost a naval war to the Japanese, who half a century before was paying homage to the Manchus. Kang Yu Wei, tasked by the Emperor of Manchu to reform imperial China, argued that the reforms must be broad and deep. Of course, as history would have it, be completed in 100 days.

A Hundred Days’ Reform, in that light, is a sign of how bad things have become, not how well they could be if everyone just grits their teeth and bear it. Thus the 100-day promises of Pakatan Harapan should be seen in the same context: Malaysia was already pushed to the brim.

And, had BN and Umno remained in power any further, things could have been worse, regardless of what Najib Razak may have said after his jarring defeat on May 9.

Najib, for example, argued that at all points he had the best intentions at heart. But then hell, too, is a road paved with best intentions.

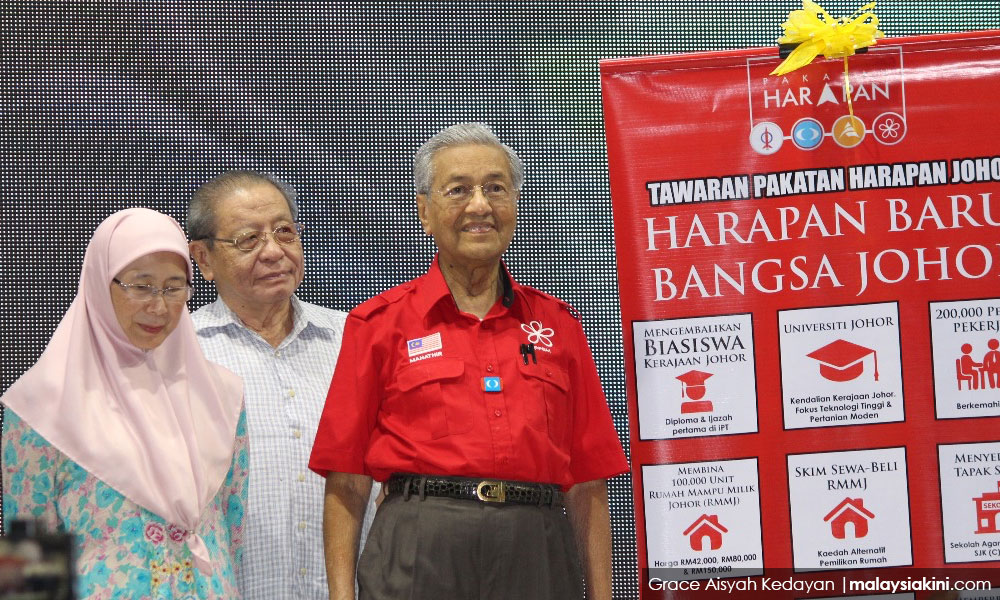

Pakatan Harapan, formed of a coalition of four parties, may also have the best intentions to save Malaysia. But if they don't carry out the 100-day reforms as promised, their promises in future would not stand up to scrutiny.

So, regardless of what Pakatan Harapan may say, its elected representatives will start with a trust and performance deficit with the people.

Need to pare down debts

One of the economists in the Employee Provident Fund (EPF) has said that the national debt does not matter as much as the ability to grow the income streams of the country. Yet such arguments are gravely mistaken. Debt, around the world, has grown from US$42 trillion to US$199 trillion between 2007-2017.

Clearly, global debts have become uncontrollable. And, the day of reckoning will come one day, as it did in 2008, when the world was confronted with the financial meltdown of the United States, especially after the collapse of Lehman Brothers.

If Malaysia does not pare down its national debt, of which 97 percent is denominated in ringgit, when a global financial meltdown hits the world, Malaysia would have nowhere to hide.

Our 100-day reforms will require Malaysians to wise up to the frailties of the world. China experienced a century of humiliation precisely because it refused to adopt the best practices in the West, especially in the sector of governance and military reforms. Japan, in turn, was saved by the Meiji reforms in the mid-19th century, without which it would not have been able to become a major power.

Indeed, urgent and critical reforms are needed, not over 100 days, but forever, barring which the machinery of the government would begin to fail. Take Britain, for example. It took its eyes off the importance of reforms and is now attempting the next thing, which is Brexit.

Yet Brexit could explode in its face too, as other member states of United Kingdom, such as Scotland, Ireland and Wales, begin to contemplate the possibility of remaining with European Union, while potentially severing its relationship with London.

If this is the dynamics in perpetual motion, all successive British governments after Prime Minister Theresa May would be wobbly.

Malaysia is now no longer immune to the idea of a government that needs to be phased out from time to time. But the 100-day reforms of Harapan deserve either more time or more leeway to make the promises work.

As a country, Malaysia has been corroded by the problem of what DAP veteran Lim Ki Siang described as kakistocracy and kleptocracy - the rule of the worst rulers and thieves, respectively. And the 100-day reforms will only be a band-aid if the reforms are not deep enough.

PHAR KIM BENG is a Harvard/Cambridge Commonwealth Fellow, a former Monbusho scholar at the University of Tokyo and visiting scholar at Waseda University. -Mkini

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.