Adolescence – that unique, halcyon phase of a young person’s life – is characterised by change and transition. These are years of encountering new experiences, building social skills and learning to handle challenges independently.

It is during adolescence that many key developments take place, physically as well as mentally. In fact, adolescence is one of the most critical life stages for building and protecting good mental wellbeing. But how much do we actually know about the mental health of young people in Malaysia?

The official data derives largely from the government’s National Health and Morbidity surveys (NHMS), which are carried out in regular cycles by the Institute for Public Health, an agency under the Health Ministry. These statistics are the closest we have to definitive information on the state of young people’s mental wellbeing.

Unsettlingly, these official figures reveal that mental health problems are more common among this age group than we care to think.

According to the 2017 NHMS conducted on 13- to 17-year-olds, two in five teenagers nationwide had symptoms of anxiety, and one in five had symptoms of depression.

The proportion of ‘at risk’ students has barely changed since 2012, when a similar prevalence sampling exercise was carried out. That year, 39.6 percent of students reported symptoms of anxiety, and 17.7 percent symptoms of depression.

Offhand, these figures may not seem very significant, especially since they do not represent actual diagnosable mental health conditions. But, lined up against data on youth suicidal behaviours, a deeper concern emerges.

Between 2012 and 2017, levels of suicidal ideation among students rose from 7.9 percent to 10 percent. In other words, one in 10 young people had seriously contemplated killing themselves.

Not all of this was entirely impulsive and fanciful thinking. Last year, one in 14 surveyed students disclosed that they had planned their attempts, while approximately one in 15 had acted on these plans and attempted to take their lives.

What is causing youth mental distress?

Put together, the evidence is jarring. In the past five years, many young Malaysians have been struggling to cope mentally, and a sizeable number had even tried to defeat their despair by self-slaughter.

There appears to be a disturbing level of psychological distress lurking among the youth in our midst. The phenomenon is deeply worrying, and begs a very basic and obvious question: why?

Drugs, drink and smoking

Besides data on prevalence rates, NHMS also presents co-occurring factors exhibited by young people who had disclosed psychological distress, which may provide significant clues about underlying causes.

First, based on NHMS 2017, substance use behaviour was found to have one of the strongest links with mental ill-health among youth. Over half of students aged 13 to 17 reporting depressive symptoms had also used drugs in the 30 days prior to taking the survey. Meanwhile, for those suffering from anxiety, the association with drug use was even stronger, with over two-thirds reporting drug usage.

High use of marijuana was found to be especially prevalent among troubled young people. Some 74 percent of students reporting anxiety symptoms had used marijuana one or more times in the past 30 days; this figure was almost matched by the 60.3 percent struggling with depression, who had engaged in marijuana use.

NHMS 2017 also highlighted associations between drinking and smoking habits, and youth mental health problems. Slightly under a third of students who disclosed depressive symptoms had smoked cigarettes at least once in the past 30 days, and 36.6 percent had consumed at least one drink containing alcohol.

For students with anxiety symptoms, the prevalence of tobacco and alcohol usage was much higher, at 47.3 percent and 52.5 percent respectively.

Social isolation

Besides substance use, loneliness appeared to be another major risk factor for youth mental ill-health, or at least a statistically significant correlation. Nearly half of students with depressive symptoms answered ‘yes’ when asked if they had felt lonely “most of the time or always during the past 12 months”. Far fewer – 15.3 percent – answered that they had not.

Likewise, over half (63.8 percent) of students disclosing anxiety symptoms were affected by loneliness, compared with the 37.2 percent that were not.

For mentally troubled youngsters, loneliness appeared to come hand-in-hand with perceived feelings of social isolation and low levels of social support. Over a third of students with depressive symptoms felt that they had no close friends, versus the 17.6 percent who felt that they did have good social networks.

Approximately half the students surveyed suffering from anxiety also felt that they did not have close friends to confide in.

Family breakdown

Another strong influencing factor was family and the home environment, particularly in the context of parental relationships and marital status.

Roughly a third of young people with depressive symptoms lived with parents who were separated, while nearly a quarter had parents who were either divorced (24.2 percent) or married but living apart (21.8 percent). By comparison, far fewer – just 17 percent – had parents who were married and living together.

The quality of parental relationships was found to affect young people with anxiety even more, with 50.1 percent living with separated parents, and a further 43.6 percent living with divorced parents, or parents who were married but living apart.

Exposure to violence

Lastly, large numbers of young people struggling with mental health issues also reported exposure to violence, though it was unclear whether these experiences had taken place in the school or at home.

Nearly 60 percent of students with symptoms of anxiety had been bullied in the past 30 days and experienced physical abuse, while almost half (49.7 percent) had been subjected to verbal abuse.

Likewise, over a third suffering from depressive symptoms had been bullied and physically abused, while nearly a quarter had experienced verbal abuse.

Data limitations

While these are useful signposts, there is a need for greater clarity on the nature of correlation and causality between different risk factors and youth mental health.

Certain factors, like social isolation and family breakdown, may have a clear impact and connection to the onset of mental distress. Others are not so straightforward.

For example, while substance abuse has been shown to be strongly associated with mental illness, it is difficult to tell whether students who consumed addictive substances had damaged their mental health due to intake, or used alcohol and drugs to medicate disruptive or uncomfortable symptoms.

Likewise, while there are high chances that exposure to violence damages mental health, it could also be the case that having a mental illness itself leads to victimisation. Research has shown that young people living with mental illness are more susceptible to being bullied or abused, due to social stigma and discrimination.

Unfortunately, data on student mental health from NHMS 2012 and 2017 mainly covers broad trends in prevalence rates. While information on socio-demographic characteristics was collected as part of the overall youth sample, these were not specifically analysed for correlations with mental health risk factors.

This lack of specificity leaves less room for nuanced interpretations, especially when it comes to understanding potential mental health disparities between different cohorts of young people – for example, the different levels of vulnerability between young men and women, and those belonging to different ethnic groups, or wealthier or poorer backgrounds.

Tackling youth mental health

As Malaysia moves forward into a new year, the government must prioritise research that drives deeper at understanding the roots of youth mental ill-health, and the context of why and how mental health problems have arisen among young people in recent decades.

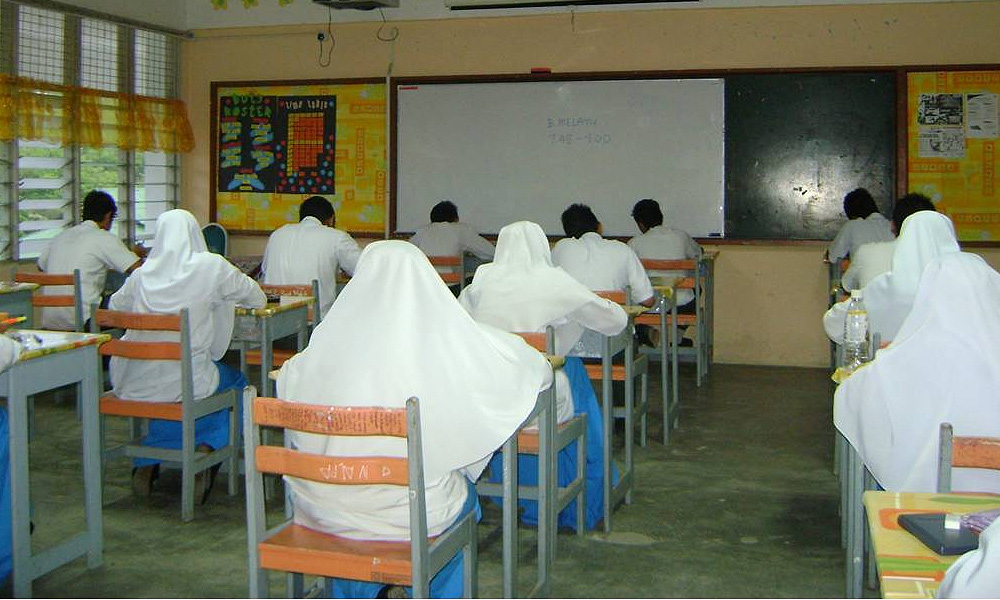

A whole population approach should be encouraged – in other words, we need to study potential risks in different levels of environments where the youth are situated, such as schools, universities, workplaces and homes.

Besides that, studies should also look into socioeconomic circumstances and the availability of social support, as well as assess levels of mental health literacy among young people, their families and the wider community. These are important factors that could work for or against a young person’s mental health state.

Such knowledge will no doubt be valuable to policy planners involved in designing health system responses, in planning for services and interventions that respond effectively to young people’s mental health needs.

However, I personally believe that designing better frameworks is only one part of solving the problem.

If we truly want to bring down levels of mental distress and encourage better mental health among young people, the solution lies in cultivating a basic understanding, at all levels of society, that the condition of one’s mental health matters a great deal, and deserves to be valued and protected in the same way that physical health is.

When our behaviours, actions and ideas stem from a fundamental realisation of this need, then together as a community, we will all get closer to sustaining and safeguarding the mental wellbeing of our young people, both current and future generations.

LIM SU LIN is a policy analyst with the Penang Institute. A History graduate from Cambridge University, her research interests lie primarily in promoting good mental health as a criterion for public policy, and to carry out research into the social, economic and cultural factors that help to enhance mental well-being and support recovery from mental distress. - Mkini

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.