The constitutional amendment under consideration in the current parliamentary sitting to lower the voting age from 18 to 21 is arguably one of the most impactful reform initiatives of the Pakatan Harapan government.

Bringing an estimated 3.8 million young people into the electoral roll, and in the process according young people the inclusion they deserve, is an important step towards strengthening the country’s democratic foundation. Malaysia not only joins the pattern of representation in the majority of the world, Harapan provides substance to the reform programme that got it elected and rewards the young for their support in GE14.

Over the past week, I have been asked which party will benefit politically and what will be the potential electoral impact of this reform. The answer is not a simple one, as it is shaped by whether other electoral reforms are adopted (automated registration and a new delineation) as well as turnout and support levels that are shaped in a yet-fought campaign.

It is important to recognise that the young will set their own path. Past voting patterns, however, suggest that all political parties can potentially gain from lowering the voting age but disproportionately, the opposition has gained more. This means that – all things being equal – PAS and Umno as opposition parties have the most to gain electorally from this initiative. Harapan, in keeping its commitment to younger voters, is absorbing the most risk in doing the right thing.

Looking back: Impactful youth favouring opposition

Youth voters (under the age of 30) have been critical in shaping the results in four of the last five elections - 1999, 2008, 2013 and 2018. They were less impactful in 2004 given the landslide nature of Abdullah Ahmad Badawi’s victory. Each election became a ‘new election’ as the share of new voters made for a different electoral pool and increased the competitiveness of the contests.

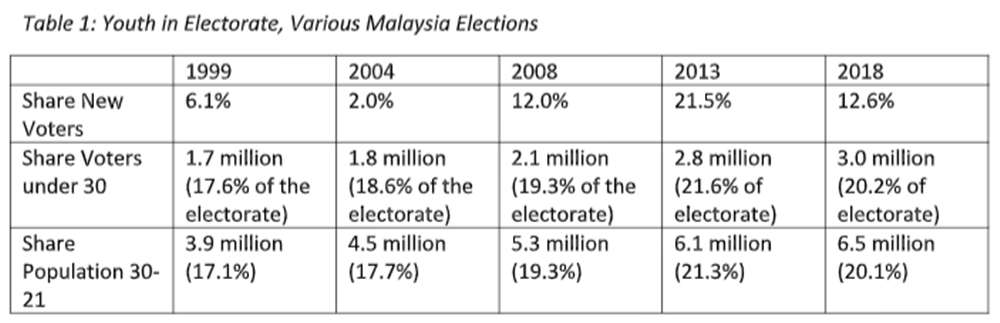

Table 1 shows the share of young voters in the past elections and the demographic impact. Youth have mattered, and as Malaysia’s share of population has grown, the number of young people shaping the results have also increased. In the last two elections, one out of five voters has been under the age of 30, although the population data shows that even more are not registered, with more than half of younger voters not registering. Younger voters could matter a lot more.

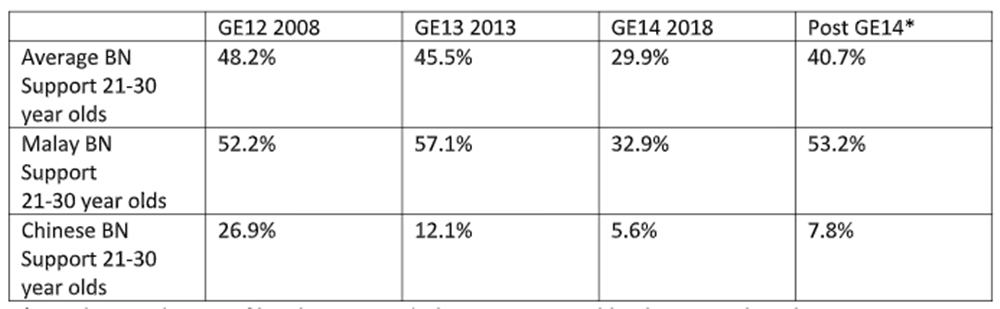

It was not until 2008 that young voters were recognised as having a meaningful electoral impact, influencing the outcome and helping Pakatan Rakyat to break the ruling coalition’s two-thirds majority. Umno and BN lost support among young people, in part due to the rise of petrol prices, disappointment with the Abdullah government and the increasing demands for “change”. It was estimated, looking at stream (saluran) results, that less than a majority of voters under 30, 48.2%, supported the BN, a drop of over 25% from the previous election.

It was thus not surprising that in 2013 that BN invested in a concerted effort to woo younger voters – through engagement and incentives, including financial packages. Umno’s Khairy Jamaluddin led the Jobs Fair in 2013 and Najib Abdul Razak’s budget included a range of spending programmes from BR1M to unmarried individuals and funds for smartphones and training.

The election results were more mixed than in 2008, as BN did win some younger voters and dented the pattern that young voters primarily support the opposition. BN lost ground among younger voters overall at 47.7% but managed to win more Malay youth at 57.1% while its support among Chinese youth collapsed to 12.1%.

The GE14 campaign witnessed intensive campaigning for the youth vote on all sides. The BN launched the National Transformation 50 plan (TN50) and increased financial promises further, while Harapan capitalised on sentiments around change and disgruntlement with Najib’s economic policies. PAS on its part appealed on a conservative religious agenda as well as rode the wave of anger against the Najib administration.

GE14 showed that young voters disproportionately voted for the opposition, with a 17% drop in support for BN among younger voters from GE13. Harapan picked up 46.1% and PAS 25.6% of voters in this cohort. For the Islamist party, this was the largest share in any age group, as their voters are increasingly younger.

Yet, recent by-elections show a swing away from Harapan, as 40.7% of younger voters voted for BN (with PAS). This was an increase of 10%, and particularly important among Malay voters where an estimated 53.2% voted for BN working with PAS. The opposition pattern in youth voting has set in – with a swing away from the Harapan government to alternatives.

Looking ahead: Rewarding inclusion or performance

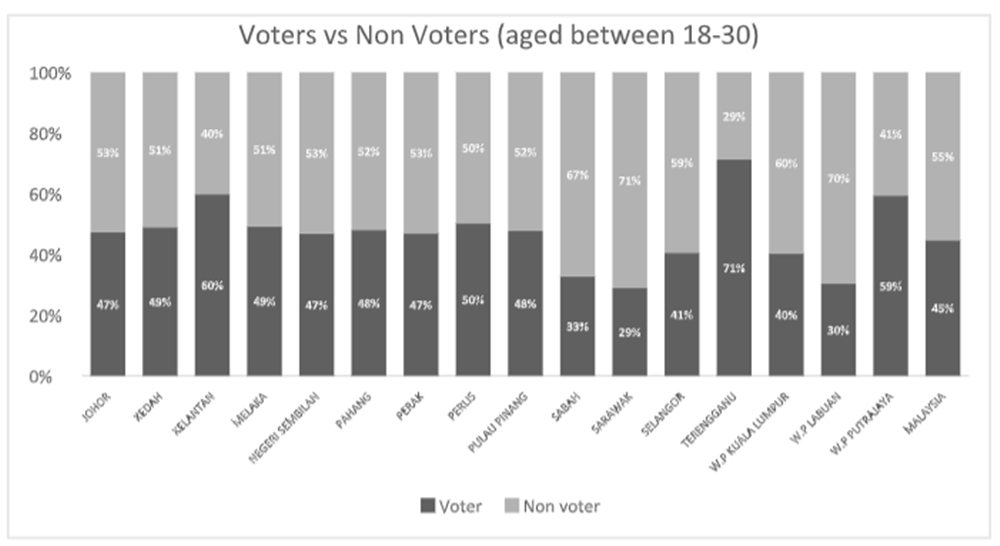

The proposed initiative in lowering the voting age would mean that an estimated half a million more voters on average would enter the electorate annually. Young voter can comprise 40% of voters in the majority of states. The share of young voters is particularly high in Kelantan and Terengganu – both governed by PAS. Large shares of young voters remain unregistered, especially in Sabah, Sarawak and the Federal Territory.

Youth voters share particular features. They are part of a cohort shaped by the context in which they entered politics. This has been the case historically in Malaysia, from the NEP Generation to 2008’s 505 Generation. Today’s 18 to 21-year-olds, Gen Z, will shape a cohort of a period of Harapan government, a period without Umno at the helm.

Beyond not registering, younger voters also turn out in lower numbers and are more disengaged with politics. This means that changing the voting age alone will not necessarily lead to younger Malaysians voting. A change in the registration system and voter mobilisation will also be important.

Younger voters are also disproportionately more connected on social media and as such, they are more influenced by campaigning on this medium. Finally, younger voters are more economically vulnerable (more than the 30 to 60-year-olds) and are also more affected by job growth (or lack thereof), inflation and economic conditions. Young voters have the lowest political literacy and surveys show a need for greater political education.

In thinking about how the young are being affected politically moving forward – two issues stand out, the centrality of identity politics being played out especially on social media and, even more important, performance in the economy. Both of these areas are challenges for Harapan, as in the former, the coalition has not been able to forge its own narrative of national identity to counter that of Umno and PAS.

In the latter, Harapan has inherited a constrained budget with the debt left by the Najib government and unfavourable global and regional economic conditions. Providing the vote to youth is arguably easier than implementing the economic and social programmes needed to win over this cohort, at least in the short term. Harapan is hoping to win youth support through two other issues – inclusion/recognition and greater engagement with the young.

Of all the political players, Harapan has the most to lose electorally in lowering the voting age. The fact that they are going ahead in proposing the amendment despite the political risks involved speaks to an honouring of an electoral commitment and the importance of the amendment itself.

For PAS and Umno, given the pattern of young voters favouring the opposition historically, supporting the amendment is largely in their political interest. This is particularly the case for PAS, which has won over more support among youth in recent elections. Umno may likely gain from disgruntlement (as has happened in a number of by-elections) but given the significant erosion of support from the party over time, gaining youth support will require significant changes to the party. At this point, Umno does not appear ready to implement reforms, namely a new leadership and different patterns of engagement.

Yet, if Umno (or PAS) opt(s) to oppose the amendment, they stand the risk of further alienating support among the youth. Refusing to empower the young for political reasons could be seen as cowardly and could backfire against Umno (or PAS) at the ballot box.

Ideally, the decision however should not be based on the interests of particular parties, but what is good for Malaysia as a whole. It is hoped that the political parties will look beyond interest to the greater good; empowering youth, the same youth that can drive and serve the nation in the military and police at 18, would go a long way to strengthening Malaysia – and accompanied by other electoral reforms and improvements in civic education, will be a crucial move toward truly building a ‘new Malaysia’.

BRIDGET WELSH is an associate professor of political science at John Cabot University in Rome. She also continues to be a senior associate research fellow at the National Taiwan University's Centre for East Asia Democratic Studies and The Habibie Centre, as well as a university fellow of Charles Darwin University. Her latest book is the post-election edition of ‘The end of Umno? Essays on Malaysia's former dominant party.’ She can be reached at bridgetwelsh1@gmail.com. - Mkini

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.